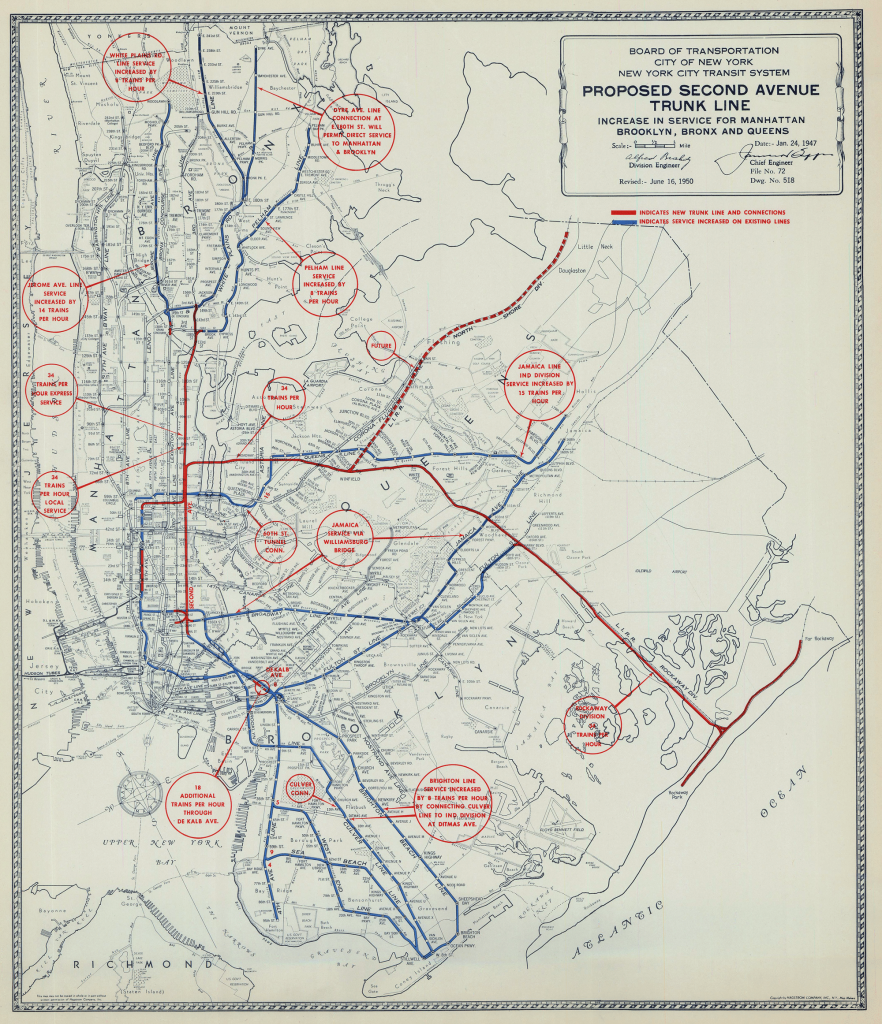

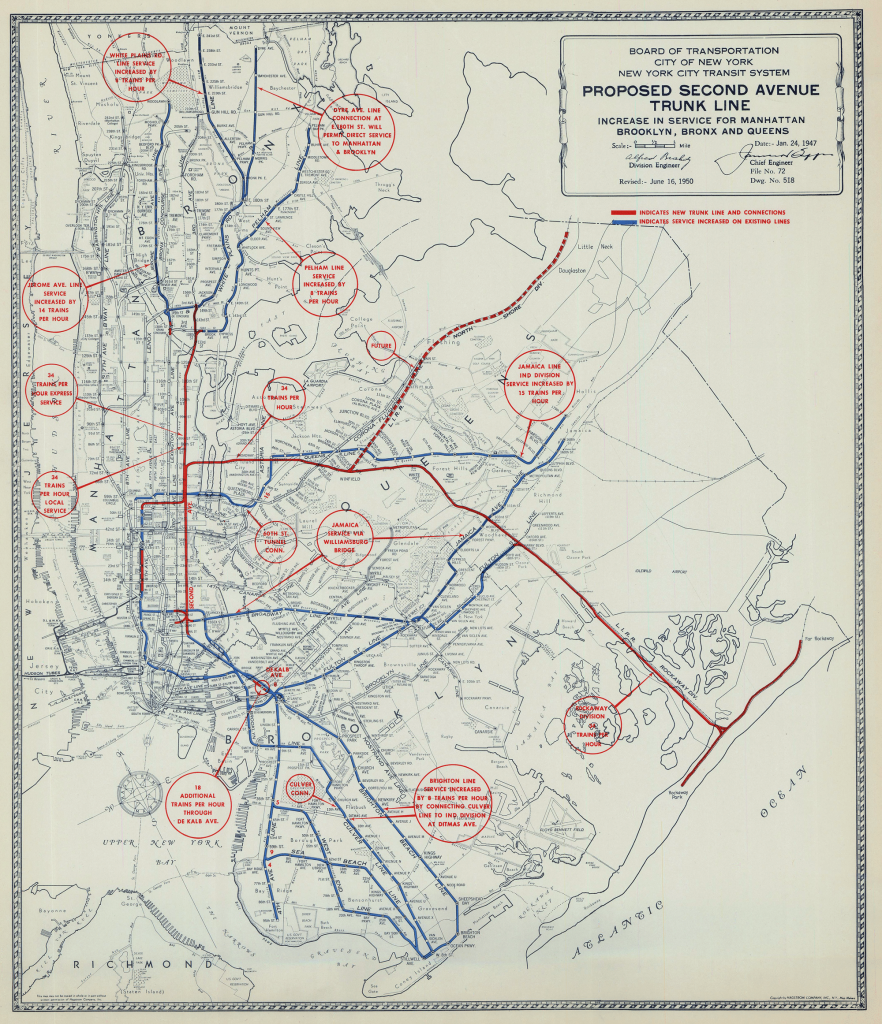

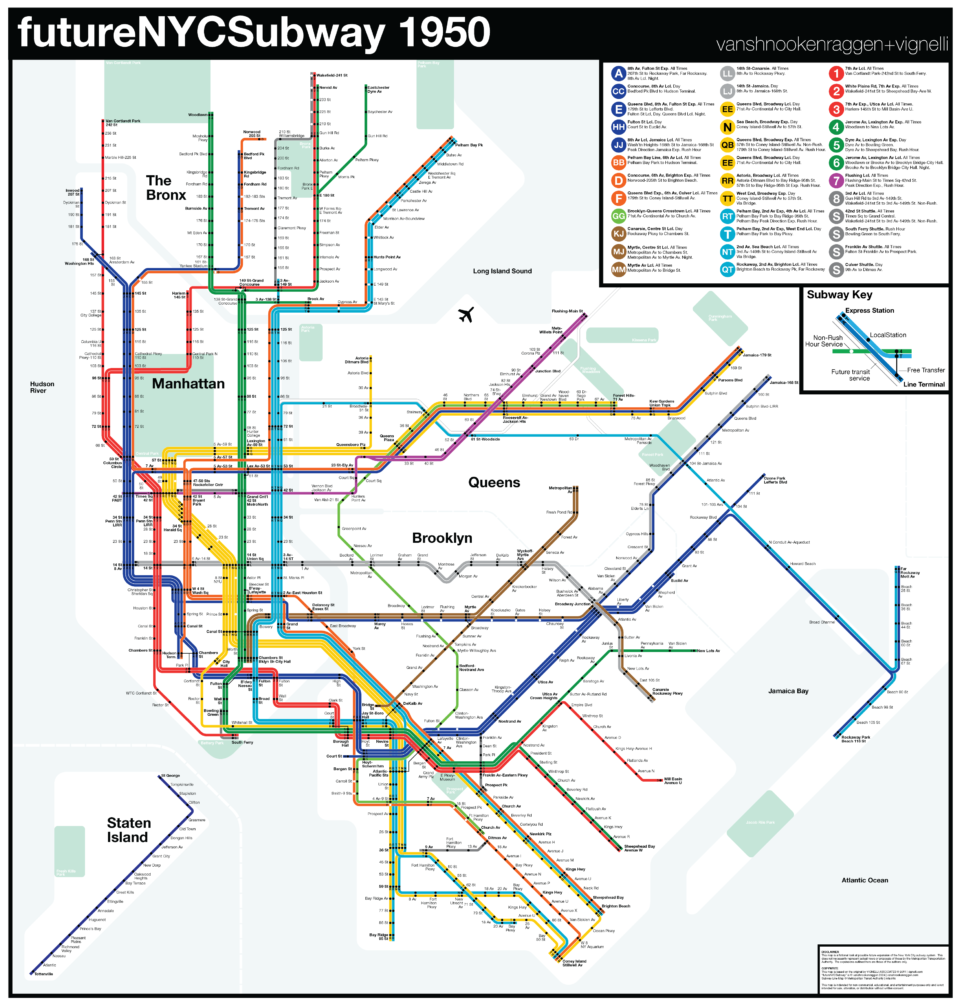

The idea for this post came from an overlooked appendix at the end of “The Routes Not Taken”, the definitive history of the unbuilt New York City subway lines by Joe Raskin. In the appendix, Raskin outlines the proposed new services for the 2nd Ave Subway based on a 1947 plan released by the Board of Transportation. The proposal was the first to include the Chrystie St Connection, which was eventually built and radically changed how we thought about the subway.

One of the failings of early subway maps, both for actual service and proposed new lines, was that they never showed the routes that would actually be run. Naming conventions have evolved over the years, but any New Yorker knows what the A train, or the 4 train, or even the Z train (which some people still swear isn’t real) is. The appendix from “Routes” actually lays out each new route. So, naturally, I had to map it.

The new plans were rather ingenious. Rather than focusing on new lines, the 1947 plan took advantage of the newly unified network and used the 2nd Ave Subway as a way to enhance service on existing lines. While the 2nd Ave Subway was never built out to support all the new services, the Chrystie St Connection and other smaller connections were able to transform the network as planners had hoped. It was one of the few expansion ideas that bore fruit.

That got me thinking about how the mid-20th Century subway plans evolved to that point, or rather, devolved. In the history of the New York City subway, the specter of the IND Second System looms large. It exists in the distance of our collective mythology of the alternative history that could have been if only Robert Moses hadn’t built all these roads. If only we had chosen a world which revolved around mass transit and not private automobiles. If only.

Myths are stories we tell ourselves that simplify the truth so that we can all agree on it. It’s a shame that the truth isn’t always so simple. The same could be said for the IND Second System, and why it was never built. When we break the world into simple good and evil, we lose the context that is truly required to understand why we ended up the way we did. In a sense, it’s a lie to make ourselves feel better. But by failing to understand the true story, we seem doomed to repeat it.

Second System(s)

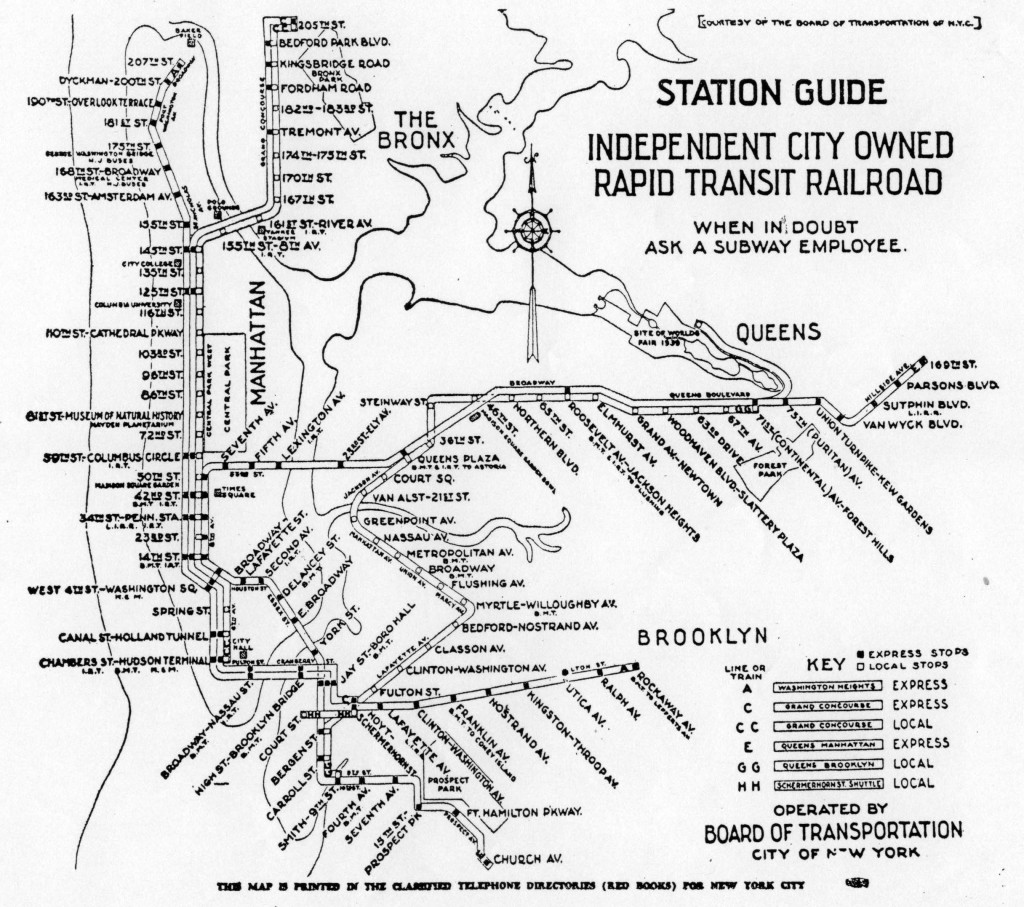

To understand the Second System, and why almost none of it was actually built, we have to define the First System. What is considered the First IND System are those lines built by the Independent (IND) City-Owned Subway System between 1925 and 1940. These include the 8th Ave Line, the 6th Ave Line, the Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Line, the Queens Blvd Line, the Concourse Line, and the Fulton St Line. Today, these lines are better known for their single letter identification: A/C/E, B/D/F, & G trains. While the railroad was called the IND in shorthand, all planning and construction was managed by the new Board of Transportation (BOT), John Delaney, chairman.

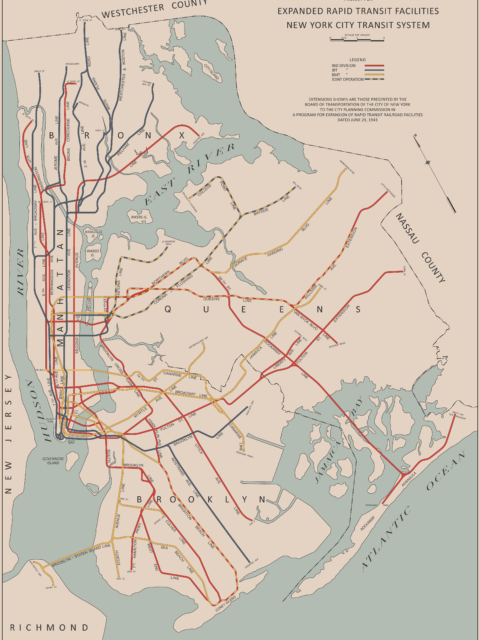

What we refer to as the Second System isn’t actually one single plan that was never built. It’s an eponymous term given to a collection of ideas that had been proposed between the building of the First System and the creation of the New York City Transit Authority in 1953. Some of these proposed lines had small sections built so that future construction would be easier. Other proposals never got off of the drawing board. There is no single “Second System”, rather, it was an ongoing evolution of ideas.

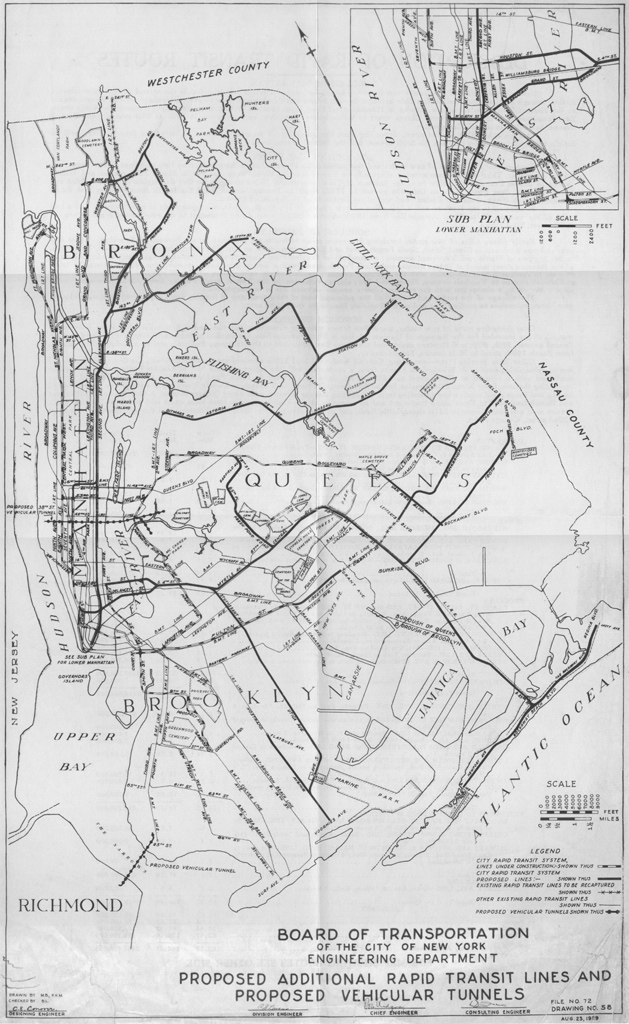

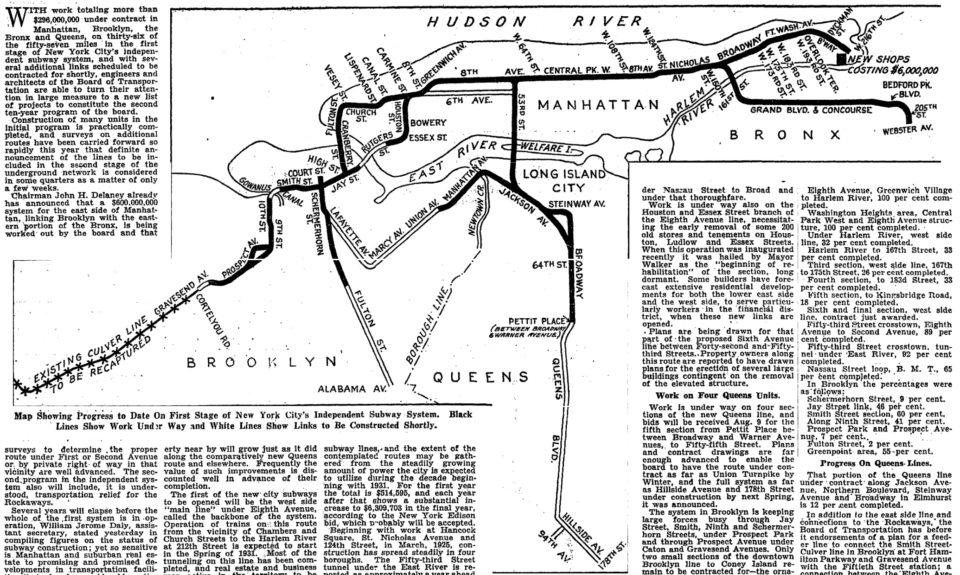

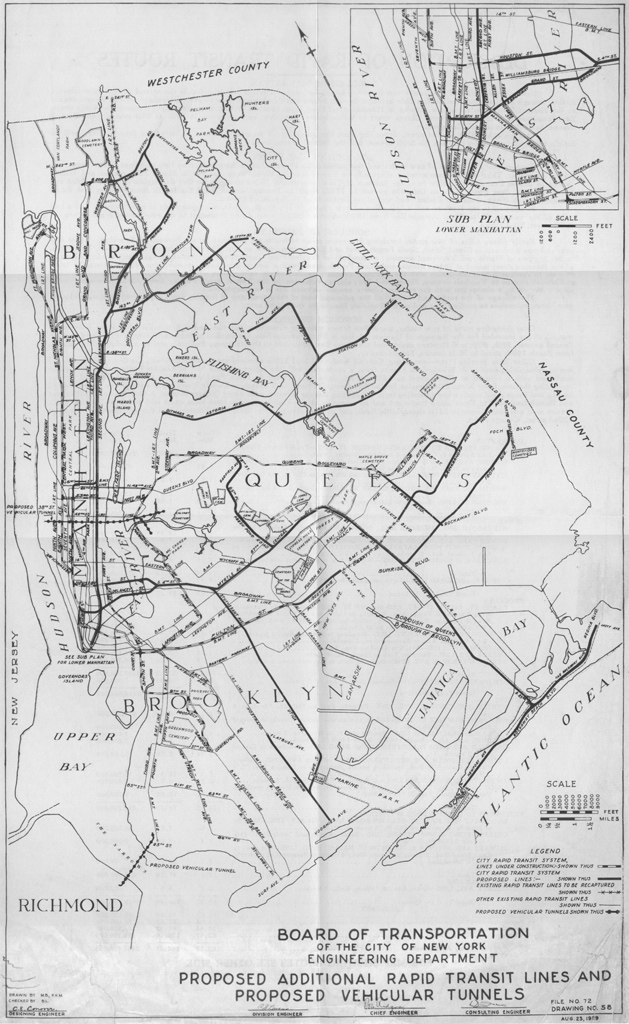

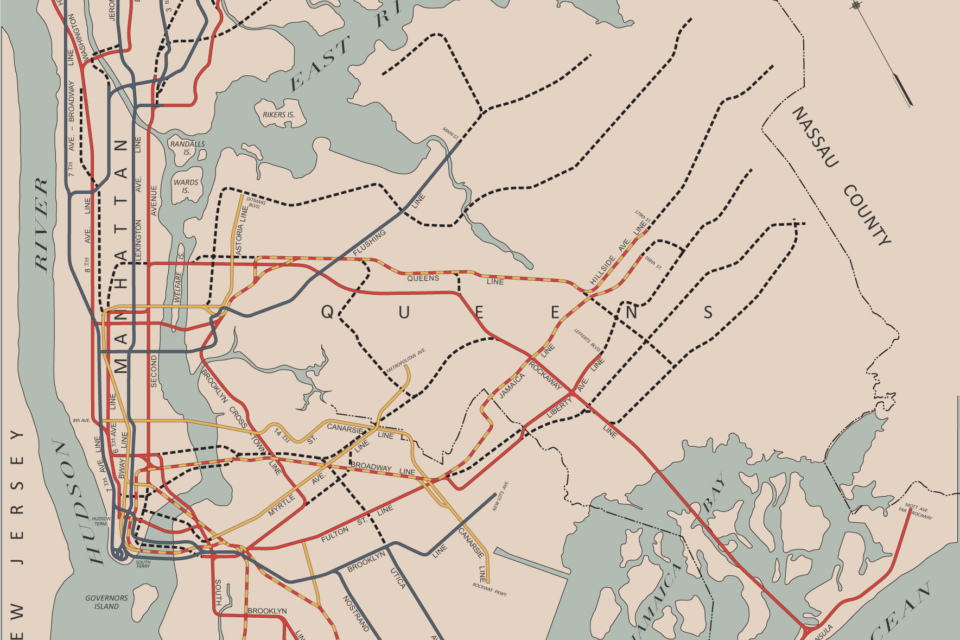

1929

In 1929, with construction on the First System well underway, the BOT ambitiously proposed a plan for a next phase of expansion. This plan is by far the most ambitious of the lot. The core of the plan was built on two major new trunk subway lines: the IND 2nd Ave Subway and the IND South 4th St Subway. The IND 2nd Ave Line was designed to reduce congestion on the IRT Lexington Ave Line, while also replacing the aging 2nd Ave and 3rd Ave elevated trains. The IND South 4th St Line was a giant sorting machine which combined two large subways out to Utica Ave and the Rockaways through Williamsburg and up 8th Ave or 6th Ave. This line, too, was designed to replace the elevated Jamaica and Myrtle Ave Lines.

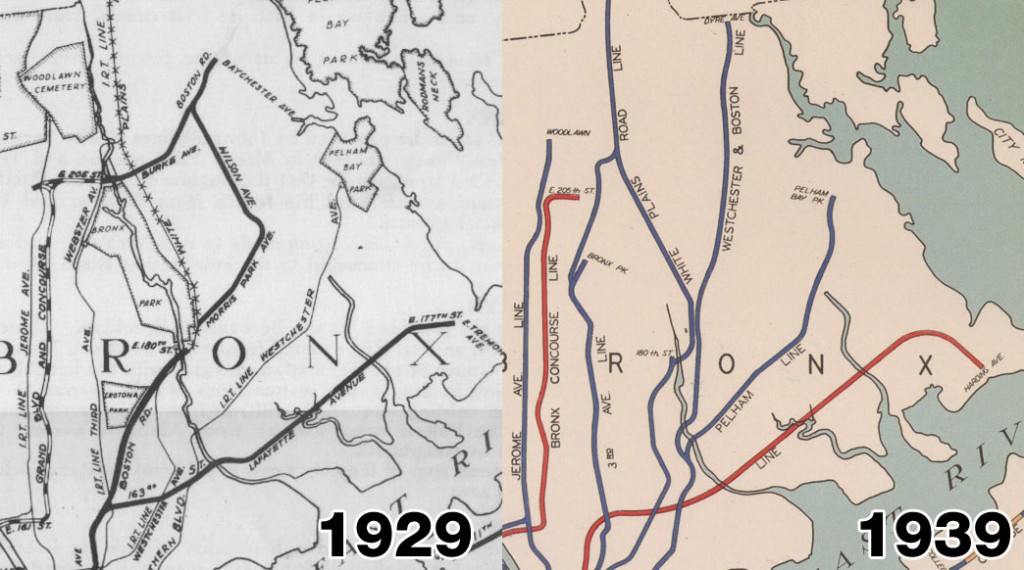

The IND 2nd Ave Line was to extend into the Bronx and would split, with a new branch running to Throgs Neck along Lafayette Ave, and another to the northeast Bronx along Boston Rd, Morris Park Ave, and Wilson Ave. The IND Concourse Line was to be extended from Norwood over to link up with this 2nd Ave branch.

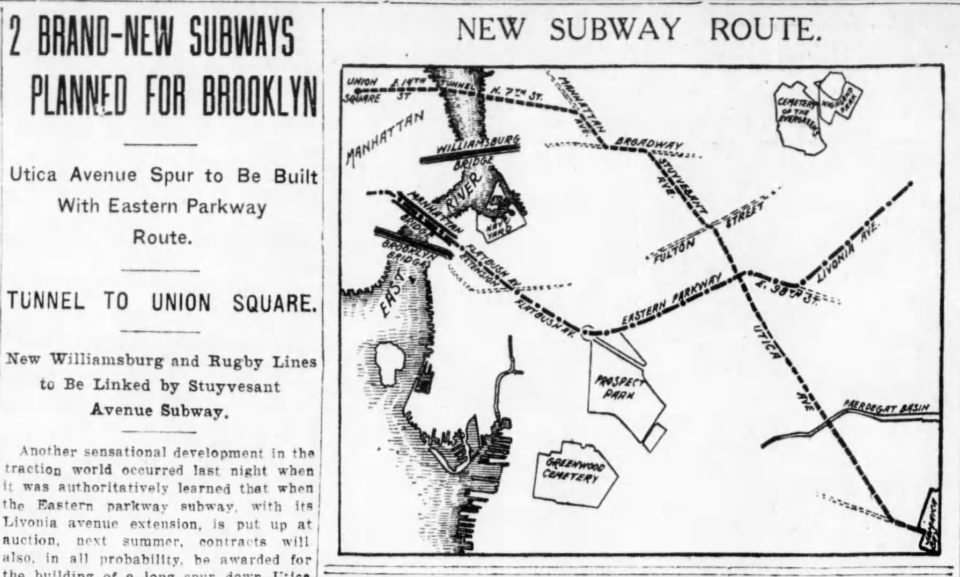

The Utica Ave Line had previously been proposed by the IRT as a branch off of their Eastern Parkway Line (2/3/4/5). The IRT had wanted to build an elevated line down Utica Ave, but faced protests from residents. Congestion on IRT lines meant that efforts to build the extension had stalled, so the BOT picked up the idea and incorporated it into their future plans. A similar move had been made early in the planning of the First System, where the BMT had wanted to build a Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Line as an elevated, but was blocked by residents. The BOT incorporated this plan into what is today the G train.

By the mid-1920s, the Long Island Railroad had shown interest in divesting itself from rapid transit service on its lines, in favor of more lucrative long distance service. The Manhattan Beach Branch had been closed after the opening of the BMT Brighton Line (that is, when the Brighton Line had been connected to the subway). The Rockaway Beach Branch was now the only LIRR line which ran entirely within the city limits (though loop service through Valley Stream was also available.) The city indicated that it was interested in buying the line, should the LIRR ever want to sell (at a reasonable price).

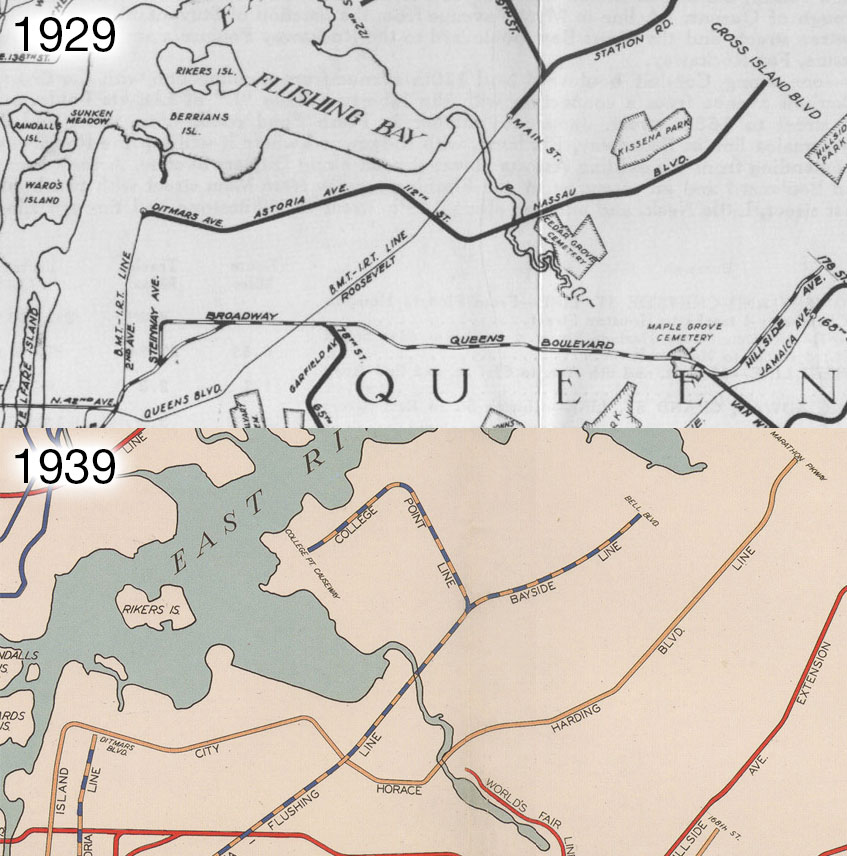

The IND Fulton St Line, under construction up to Alabama Ave, was planned to link up with the existing Liberty Ave elevated, which itself was to be extended to Jamaica. Extensions of other lines were proposed, such as the BMT Astoria Line through East Elmhurst and Flushing, the IRT Flushing Line to Bayside and College Point, and the IRT Nostrand Line to Sheepshead Bay. The inclusion of these extensions is interesting, as the city had previously prevented the other private transit companies from expanding on their own.

The IND had been financed by debt, with revenue intended on repaying the bonds with interest. In 1904, the fare was fixed at 5 cents. By the late 1920s, the 5 cent fare was not worth what it had been due to inflation. The city knew that it couldn’t afford to build and run their new subway on a 5 cent fare (newspapers at the time suggested that the fare should be 7 or 8 cents). Having a higher fare than the competition was both politically and operationally impossible. The city moved forwards in the hopes that the new lines would siphon off enough ridership from the other systems that it could break even. In order to support issuing more bonds to keep paying for construction, the Second System was announced as a way to sell the city on continued expansion. The plans were published on August 23, 1929. Two months later, on Black Tuesday, the stock market crashed and plunged the nation into the Great Depression.

The city was able to open the first line of the IND, the A train from Inwood to Chambers St, in 1932, but funds for continued construction ran out sooner than expected. The IND had been proposed during the heights of the Roaring 20s, and featured larger stations and more complex tunnels with larger curves. This was in response to many of the issues that had plagued the original systems (poor track design, crowded platforms, limited capacity, etc.) But these improvements came at a much higher cost. The realities of the Great Depression 1930s meant that the borrowing couldn’t continue, and work on the system stopped.

New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt was quick to try to get people back to work with progressive new policies. But the state could only do so much. When he was elected president in 1932, he brought these same policies to Washington, and had the power of the nation to back them up. One of the many agencies formed to invest in infrastructure was the Works Progress Administration. This, for the first time, allowed federal money to be directly invested into infrastructure projects as a way to get people back to work.

Mayor Fiorella LaGuardia, who had a good working relationship with the former Governor, was famous for his trips to Washington where he was able to, time and time again, secure funds for works-projects. It was through WPA grants that he was able to secure the funds to complete the IND by late 1940. Both construction and planning was restarted. BOT planners had learned much in the years since work had started, and had felt pressure from civic groups who wanted to see lines through their neighborhoods. But they were also keenly aware of the real costs for construction, and the new costs of running a railroad.

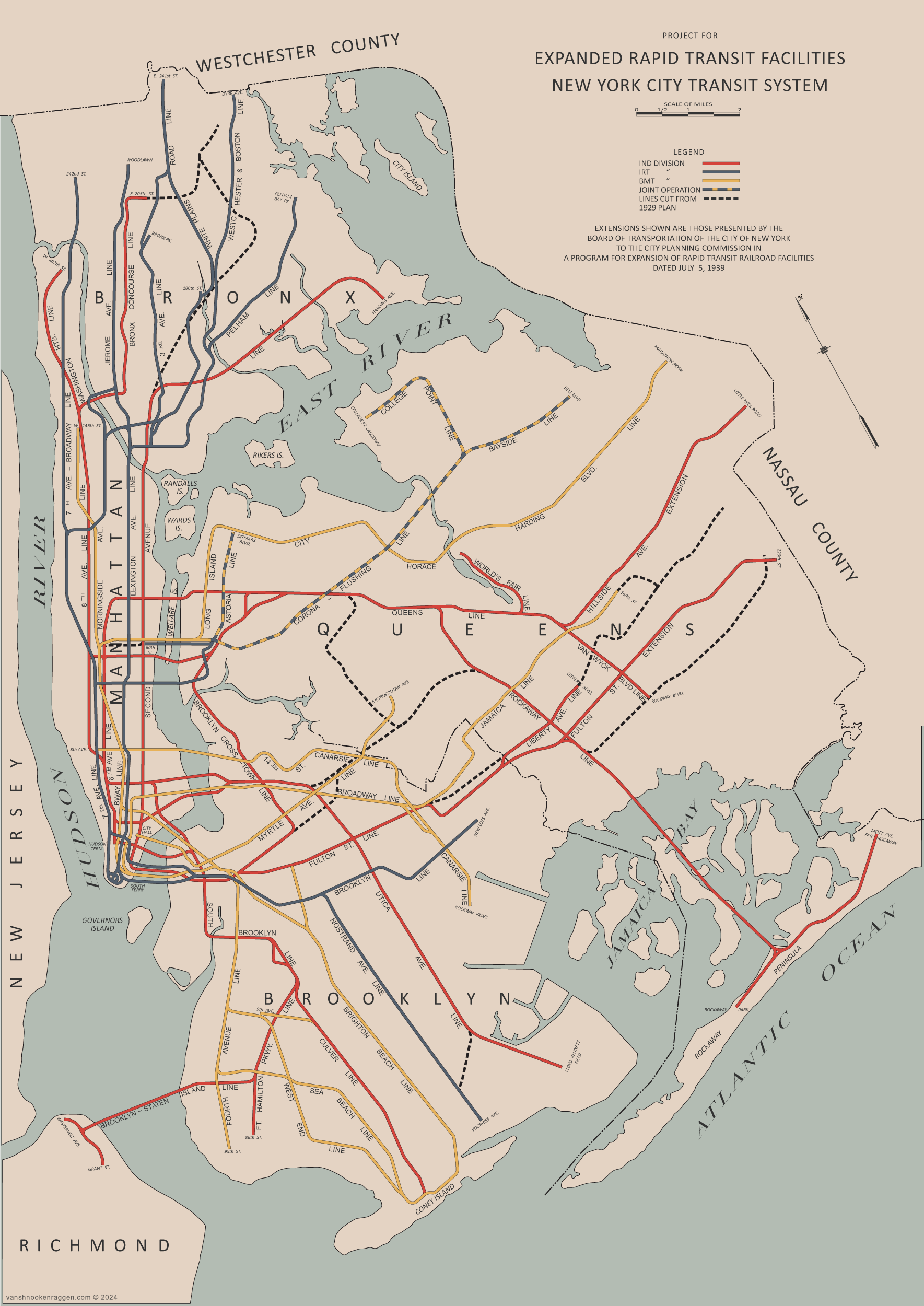

1939

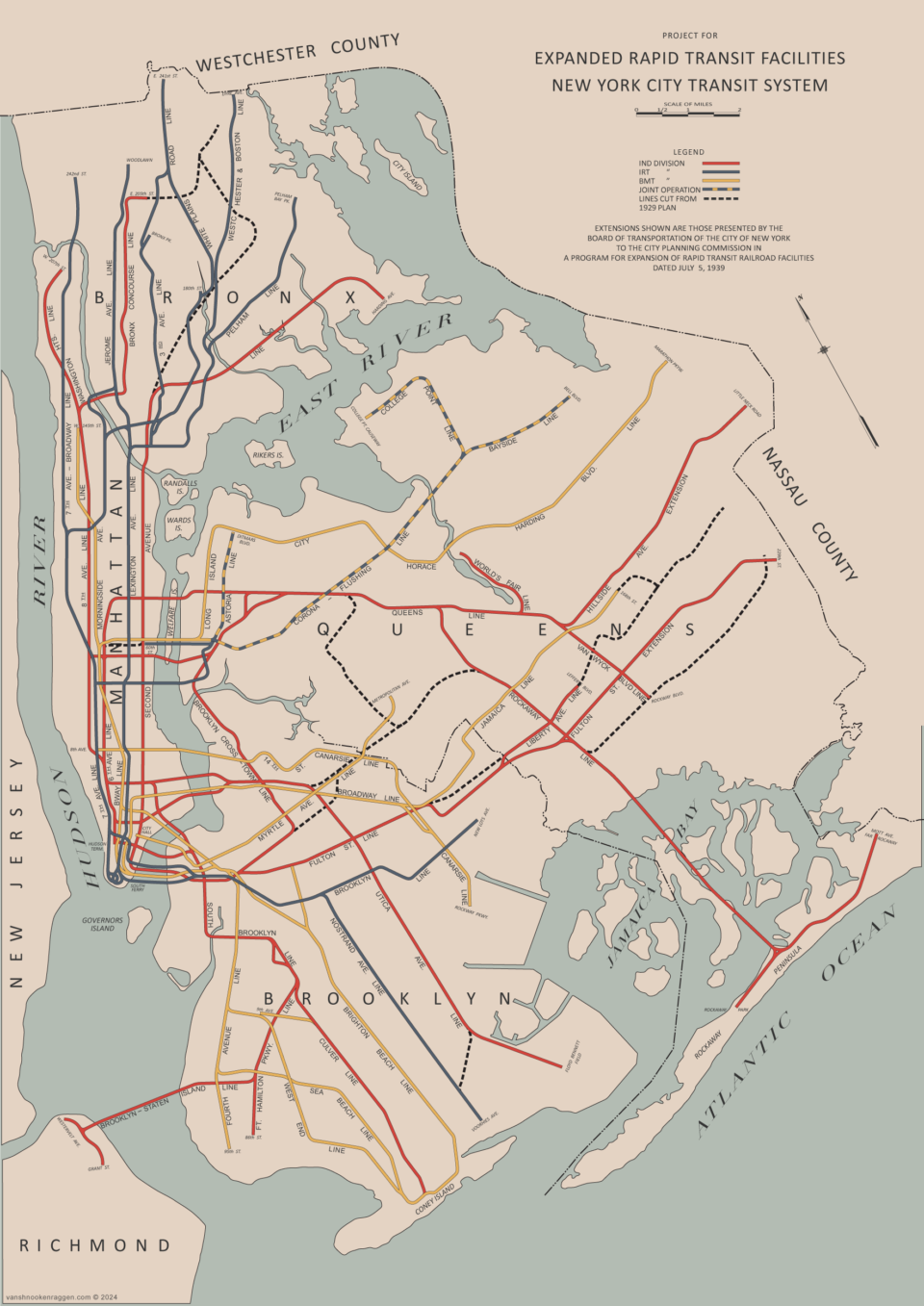

By 1939, one year before the IND was considered “complete” with the opening of the IND 6th Ave Line, plans for the second phase had evolved based on public feedback, construction costs, and ridership data.

The IND 2nd Ave Line and IND South 4th St Lines were still the major components of the plan. But the lines once planned for central and southern Queens had been simplified or cut entirely. The IND Utica Ave Line was still there, but the IND Rockaway Line, originally planned to connect with the IND South 4th St Line, was now going to connect with the IND Queens Blvd Line. This removed a large section through Ridgewood and Glendale that had been intended to replace the elevated Myrtle Ave Line.

The route of the IND Fulton St Line had been finalized as a subway along Pitkin Ave. The planned elevated extension to Jamaica had been cut early on, due to protests against new elevated lines. Service to Rockaway Blvd had commenced in 1936, while work on the next phase to Euclid Ave was started. The line would replace the existing elevated line up to the border between Brooklyn and Queens. Here, the BMT Liberty Ave elevated (which had been built by the city as part of the Dual Contracts) was to be connected with the subway, while the subway would continue deeper in the southern Jamaica along Linden Blvd. Service on the IND Fulton St Line was to be increased with a connection to the IND 2nd Ave Line.

In the Bronx, the complex branches proposed for the IND 2nd Ave and IND Concourse Lines were rendered moot when the city was able to purchase the bankrupt New York, Westchester and Boston Railroad (NY, W & B RR) for conversion into a subway line. This would be connected to the IRT, eliminating the need for more IND service through the northeast Bronx. Instead, the BOT moved all 2nd Ave service to the Lafayette Ave Line to Throgs Neck.

To compensate the Bronx for the loss of new service, a connection between the IRT Lenox Ave Line (today, the 3 train) and the Jerome Ave Line (4 train) was proposed as a way to double service to the Bronx. To provide more service to West Harlem and Upper Manhattan, the BOT proposed extending the express tracks of the BMT Broadway Line at 57th St to 145th St in Hamilton Heights. This would provide more service on either the Washington Heights Line or the Concourse Line.

Ridership in Queens had exploded with the introduction of subway service. The BOT had originally designed the IND Queens Blvd Line so that all local trains served the IND Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Line, while only express trains ran into Manhattan. This was immediately problematic when demand for Brooklyn service proved to be far lower than expected, and demand for Manhattan service far higher. A new tunnel between 6th Ave and Queens Blvd was proposed. This tunnel would be built around 76th St, and connect directly to the IND Queens Blvd Line local tracks at Steinway St.

This new tunnel would provide service to the IND Rockaway Line, and more service to Jamaica. In Jamaica, the spur down Van Wyck Blvd remained, while the IND Queens Blvd Line along Hillside Ave was to be extended from 169th St to Little Neck Rd. To save money, the BOT had opted to build a less than efficient terminal at 169th St, which limited express train service. A better terminal station was planned as part of the next phase, but with ridership on the express lines bursting, an extension with a more efficient terminal was soon becoming a priority.

In northeast Queens, the same old extensions of the IRT Flushing Line to Bayside and College Point were still included. The extension of the BMT Astoria Line was changed to a new line, with service from the BMT 60th St tunnel and a rerouting of the IND Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Line.

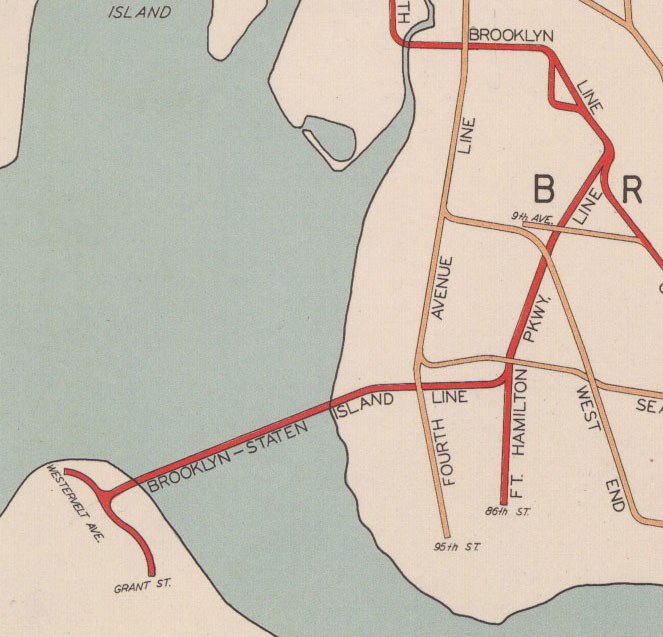

A tunnel to Staten Island had been proposed as far back as 1900. When the BMT 4th Ave Line was built as part of the Dual Contracts, provisions were built for a future connection to a tunnel under the Narrows. Work had even started on a tunnel in 1924, but a disagreement between the city and state over who would use, and therefore pay for, the tunnel stopped all work indefinitely. By 1929, this dispute had not been resolved, and it’s worth noting that no subway to Staten Island was proposed as part of the 1929 plan.

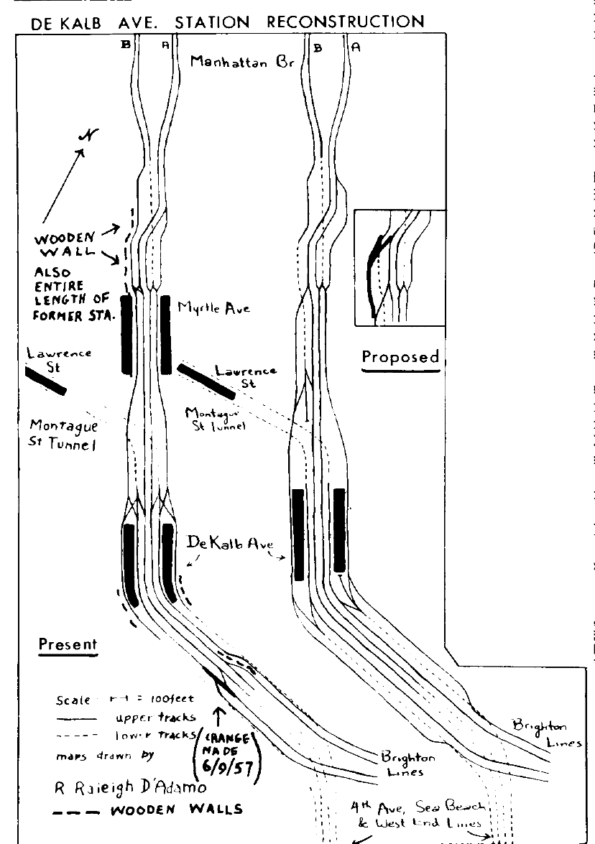

Service on the many southern Brooklyn BMT lines had been dismal ever since the subways opened. The cause was very poor track design at the DeKalb Av station, which required trains to switch tracks in front of one another, backing up service. Too many branches being connected to too few tracks greatly limited service on the new subway lines. This was a primary concern for any proposed Staten Island Line. But in the 1939 plan, an even more ambitious proposal than that from the Dual Contracts appeared.

The IND South Brooklyn Line was designed with 4-tracks. The local tracks were to be served by the IND Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Line, while the express tracks were to be used for Manhattan-bound service from Coney Island. By 1939, the connection between the two systems had not yet been built, and the line ended at Church Ave. The BOT had intentionally designed the IND South Brooklyn Line to “recapture” the BMT Culver Line. The Culver Line had been built by the city as part of the Dual Contracts, but was leased to the BMT. Recapturing the line would redirect all Culver Line trains through the IND, allowing the former service to be spread across the other BMT lines.

Planners knew that there was ample capacity on the new IND subway that could greatly reduce crowding on the BMT lines. At the behest of local business groups, a new IND branch was proposed from the South Brooklyn Line along Fort Hamilton Pkwy. This line would continue south, with one branch ending at 86th St, while another would turn west at 67th St and cross over to Staten Island. While not providing new service on the BMT lines, these branches would siphon riders so that congestion would be reduced.

1940-1944

In 1940, the private subway companies called it quits. Their profits had dried up, their operating costs were rising, and they couldn’t afford to maintain their systems all on 5 cents per rider. The IRT and BMT were sold to the city, which now could run all three systems under the Board of Transportation. Unification, as it was known, had been advocated for by citizens and city officials alike since the 1920s. This would finally allow riders to transfer between systems for free, whereas before it would have cost a second, or third fare. Lines, such as the IND South Brooklyn and BMT Culver, could finally be connected, boosting service for all of southern Brooklyn.

BOT planners got to work on new ideas for physically connecting the systems. The South Brooklyn-Culver Line and Fulton St-Liberty Ave Line connections were still present. New connections between the BMT Broadway Line through the 60th St Tunnel and the IND Queens Blvd Line were proposed. A new joint IND-BMT subway along Northern Blvd, out to Horace Harding Blvd was proposed as an alternative to the previous BMT Astoria Line extension. The Astoria Line would be extended to the new North Beach Airport, later renamed after Mayor LaGuardia. To reduce crowding on the south Brooklyn BMT lines, the BMT West End Line was to be connected to the IND South Brooklyn Line, and a new branch of the IND Brooklyn-Queens Crosstown Line was to replace the BMT Franklin Ave Line, connecting to the BMT Brighton Beach Line.

World War II delayed all work on the subways, both expansion and maintenance. This was a double-edged sword for the city, which could not invest in the system, but was making a profit due to oil and gas rationing that forced commuters back onto the system. While this was a boon for the city, this put even more wear and tear on an already dilapidated network. 1945 was the last year that the subways made money. When the War ended, and the gas rationing that came with it, riders began returning to their cars. Service began to suffer as the system was now in the worst shape it had even been in.

John Delaney had been the very first chairman of the Board of Transportation. As such, he had taken on the role of champion for subways, and had promoted subway expansion heavily. The maps published in newspapers were often PR stunts to gain support for more money, debt or federal, to keep the system alive. Even when the high costs of expansion and running the system became impossible to ignore, Delaney kept an ever evolving map of proposed new lines.

In 1946, Delaney retired and was replaced by Gen. Charles Gross. Gross was not Delaney, and he inherited not just one underfunded system, but three. Inflation after the war cut into revenue even more, and Gross realized that the fares had to be raised in order to keep the system from collapsing.

1947-1951

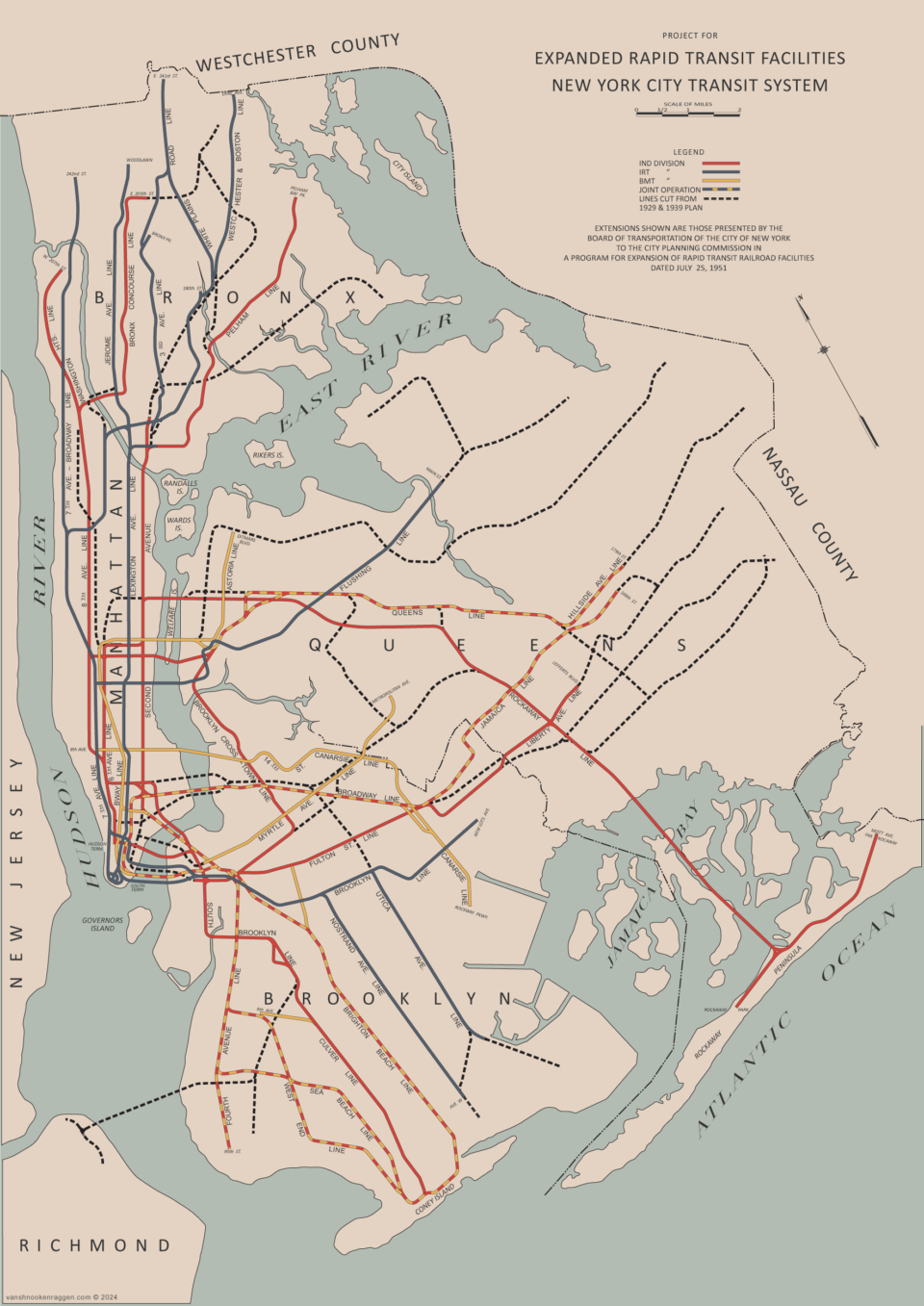

Two important extensions had been put on pause by the War. The IND Fulton St Line extension to Euclid Ave had been partially built, and work resumed. The extension of the IND Queens Blvd-Hillside Ave Line from 169th St to 179th St to improve capacity broke ground in 1946 (opening in 1950). But the South Brooklyn-Culver Line connection was still sitting idle. The proposed connection between the BMT 60th St Tunnel and Queens Blvd Line, which would add new Manhattan-bound local service in Queens, was a priority, but funding wasn’t available.

Gross didn’t last long. The new mayor, William O’Dwyer, saw the subway as a drain on city resources, especially when the Transit Workers Union demanded pay raises. Both Gross and O’Dwyer knew that the fare needed to be raised, but Gross fought the mayor on how. Soon, Gross resigned, and was replaced by William Reid. Reid knew what Delaney knew, which was that if you were going to ask for more money, you needed something to show for it. In December 1947, the BOT released a new expansion plan as a ploy to gain support for the fare increase.

The 1947 plan is not usually considered as part of the IND Second System, as by this point the subways had been unified. Old habits die hard, and both the public and subway management kept the three separate names for long after. I consider this the final Second System plan for two reasons. The first is that it was always the Board of Transportation which published the plans, never the IND itself. Second, the 1947 plan, like the previous plans, revolved around the 2nd Ave Line.

The final plan was, relative to the earlier plans, bare bones and a more realistic admission that the city could never afford to build the lines that had seemingly been promised. The 1947 plan still included a 4-and-6 track 2nd Ave Line, but gone were all traces of the IND South 4th St Line. The Fulton St Line extension, originally planned to extend out to Aqueduct Racetrack, was cut back to Euclid Ave, with a direct connection planned for the Liberty Ave elevated. All proposed extensions of existing lines into northern and eastern Queens were gone. Gone, too, were the Utica Ave and Staten Island Lines.

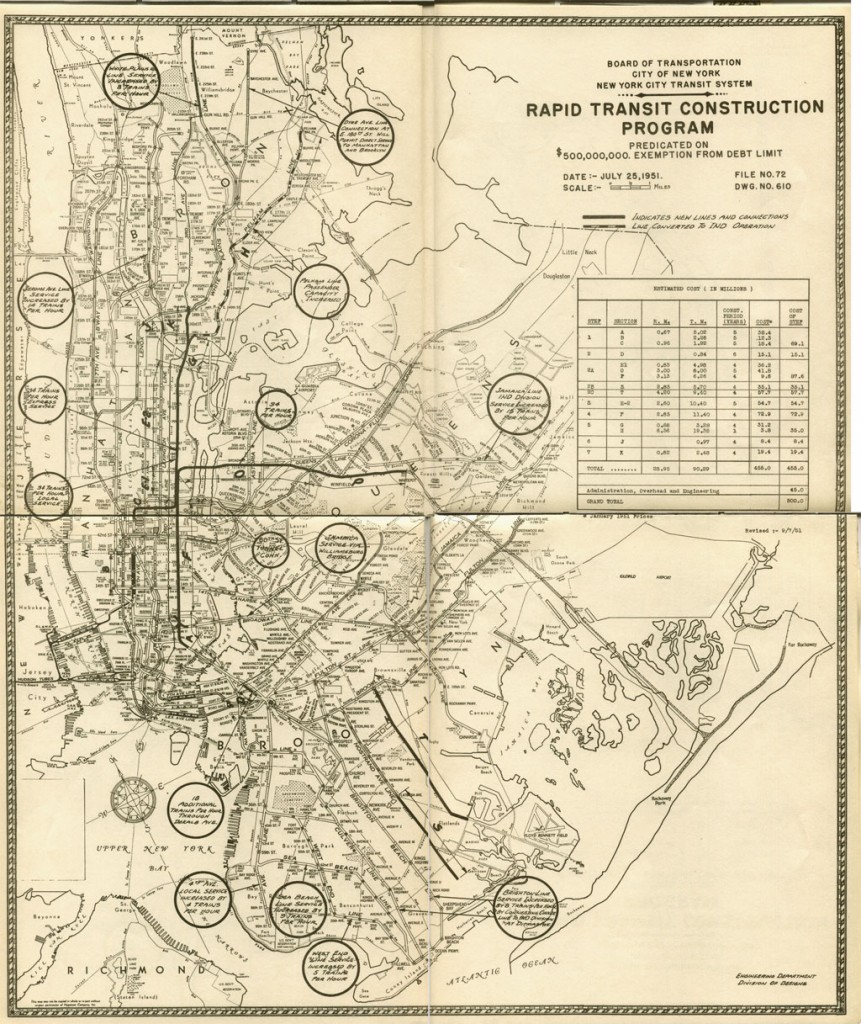

The plan was enough to buy support for a fare increase. But with inflation, the 100% increase (from 5 cents to 10) was not enough to support maintaining the system and expanding it. The city could not increase borrowing unless the state allowed it to, and there were many more projects that the city needed to invest in besides the subways. Instead, a bond measure was proposed. At $500m, it was massive. Today, that would be $6.4b. Once again, the BOT dusted off their plans for what the money could be spent on. To their credit, they did insist that much of the money would go to pay for maintaining the system, to buy new trains, and to extend platforms to support longer trains.

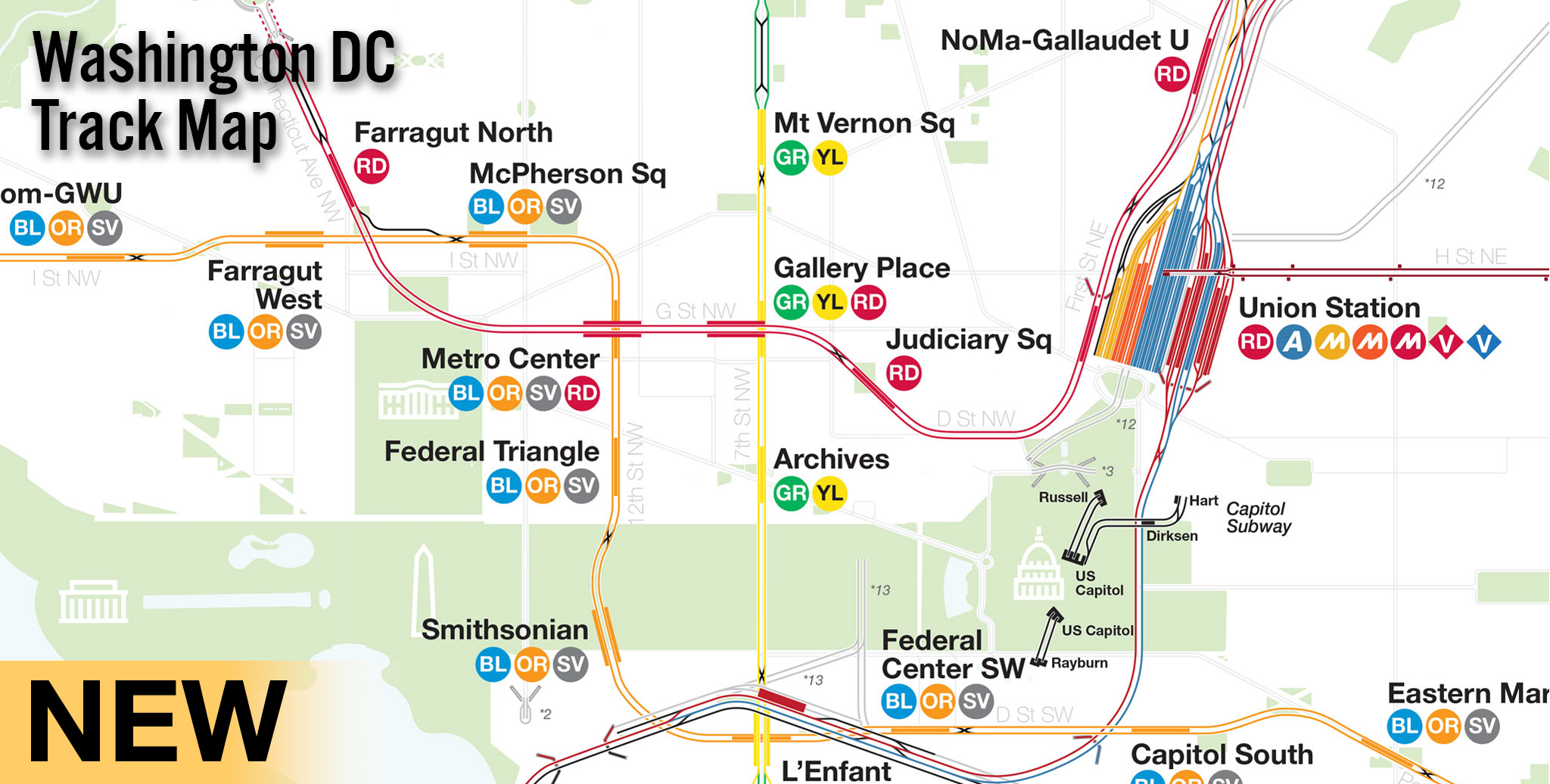

Instead of building new lines, the plan focused on connecting existing lines to improve service. This included the South Brooklyn-Culver Line connection, and the proposed connection between the 60th St Tunnel and Queens Blvd Line. In the Bronx, instead of new lines, the IRT Pelham Bay Line was to be connected to the IND 2nd Ave Line. In downtown Brooklyn, the DeKalb Ave bottleneck had long been an issue, so a complete rebuild was prioritized.

When the BOT built the IND 6th Ave Line, it had intended on building a 4-track trunk subway from 53rd St/6th Ave to East Houston St/Essex St. But between 9th St and 33rd St along 6th Ave was the pre-existing Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M). The H&M had built their 2-track line down the center of the avenue, directly blocking the IND. The BOT tried to negotiate with the railroad, but the H&M declined a buyout. For the time being, the IND would be built around the H&M, and there would be no express tracks built between West 4th St and 34th St stations.

The new plan proposed constructing the express tracks underneath the H&M tunnels. The express tracks had originally been built to support the IND South 4th St Line in Williamsburg. But with this line cut, and the systems unified, a new connection was proposed between the 6th Ave express tracks and the existing East River bridge lines. Once the express tracks were added, they would connect the IND 2nd Ave and 6th Ave Lines to the Manhattan Bridge, doubling service to Brooklyn. This connection, forever known as the Chrystie St Connection, also proposed connecting the 2nd Ave Line with the Centre St Line (J/Z trains), allowing 2nd Ave express trains to directly access Wall St, running on into Brooklyn through the Montague Tunnel.

After the War, the borough of Queens began to grow once again. It was fast turning into a bedroom community for commuters into the city. The 60th St Tunnel connection to the Queens Blvd Line was seen as a short term solution. A new tunnel under the East River would be needed sooner than later. The 1939 plan had proposed a tunnel between the IND 6th Ave Line and IND Queens Blvd Line along 76th St on the Upper East Side. Now, the same tunnel would be proposed, but would connect to the IND 2nd Ave Line first, with a spur built between 2nd Ave and 6th Ave along 57th St (a proposal originally from 1929, but dropped in 1939). However, it was unclear where this new tunnel would go, exactly.

Congestion on the Queens Blvd Line was so great that the proposed Rockaway Beach Branch connection was seen as infeasible. Taking a cue from the acquisition of the former NY, W & B RR, the BOT proposed purchasing the Rockaway Beach Branch from the LIRR and connecting it to the IND Fulton St Line extension first, and the new East River tunnel once that had been built. The BOT also hinted at the possibility of buying the LIRR Port Washington Branch as well, connecting it to the new tunnel to relieve the crowded IRT Flushing Line.

Because so much of the previous plans had been cut, a number of vocal community and business groups opposed the new plans. In the Bronx, residents of northeastern areas demanded that the BOT build the long promised extension of the Concourse Line. The NY, W & B RR had indeed been converted into a subway line in 1938, but lack of funds prevented the tracks from being directly connected to the subway at E 180th St. The BOT added this connection to the list of projects.

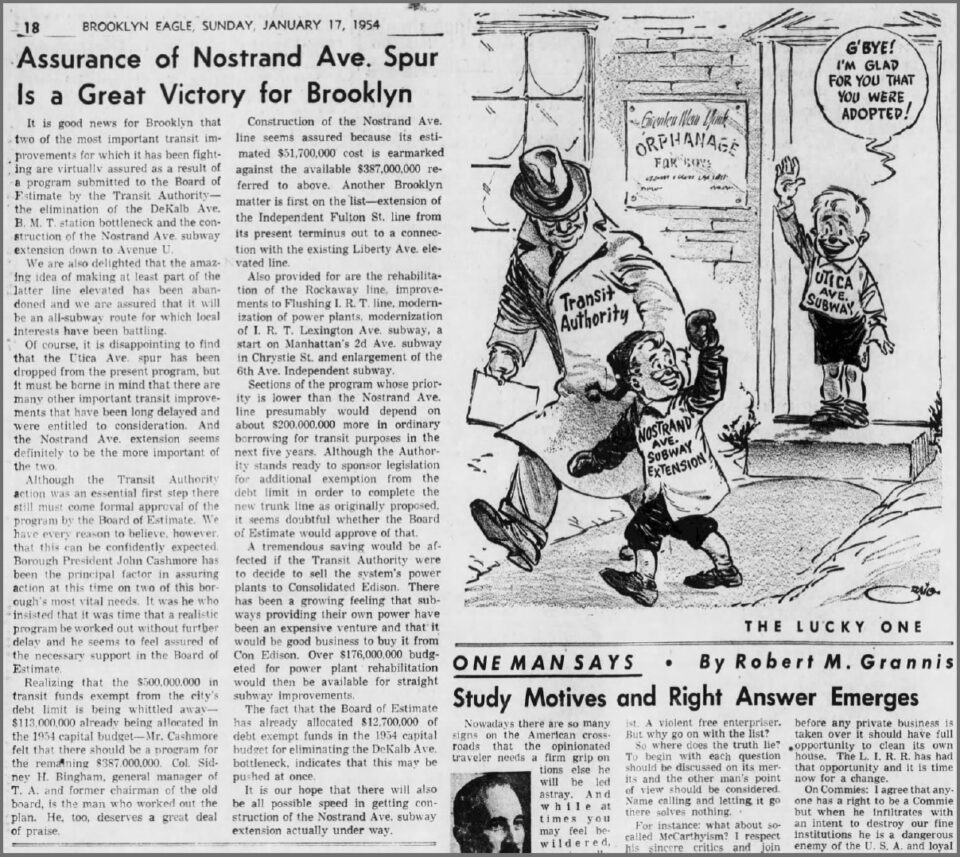

Similarly, in southern Brooklyn, residents of Flatbush and Flatlands had called for the extension of subway service into their areas for decades. The IRT had built the Nostrand Ave Line with the intention of extending it to Sheepshead Bay, as well as building a branch along Utica Ave. The higher costs of tunneling in an area with a high water table, versus building an elevated line, kept the IRT pursuing either. Every time the topic came up, residents pushed back against new elevated lines. This was also the case when the BOT took over the Utica Line. The BOT knew it would only be viable as an elevated line, but would often promise to build a tunnel to buy support from residents. The inclusion was therefore a line, as the BOT never intended to build the subway.

When it became apparent that the IND South 4th St Line was not going to be built, supporters of the Utica Ave Line changed their plans. Instead of a line from Manhattan and Williamsburg, a branch off of the IND Fulton St Line would work as a stop-gap until the longer connection could be made. The BOT pushed back at this, knowing that with the extension to Ozone Park (and potential future connection to the Rockaway Line), there would not be enough service for a branch along Utica Ave.

At this time, Brooklyn was the most populous borough in greater New York City. As such, the politicians and machine bosses held a lot of sway in the halls of government. In order to secure support for the bond measure, the BOT needed Brooklyn. However, the addition of the Nostrand Ave Line extension and Utica Ave Line would add so much extra cost that something else needed to be sacrificed. The new East River tunnel was too important to lose, but where that tunnel went could be decided later. As such, the tunnel remained, but the connection to the Rockaway Beach Branch was cut, left for a future phase.

Life, however, had other plans. In May 1950, the trestle of the LIRR crossing Jamaica Bay caught fire and knocked out service. The LIRR wanted out, and the city stepped in to negotiate a purchase. In November 1951, the $500m bond act was passed, and the city voted to purchase the Rockaway Branch from the LIRR. Brooklyn politicians worried that this would divert funds from their projects. The new mayor, Vincent Impellitteri (who had replaced O’Dwyer in the previous November), promised that this wouldn’t happen.

Not only was this untrue, an even worse reality began to emerge. The subways had been losing money since 1945, and the costs kept rising. Instead of building the new lines, the BOT used the money to shore up the physical plant, buy new trains, and extend station platforms. Work began on the important BMT-IND connections on the Culver and Queens Blvd Lines, and a large portion went to rebuilding the Rockaway Line.

Worse, still, was the inability of the BOT to manage the subways. The subways were becoming a massive drain on the city budget. Public Authorities were coming into vogue, in no small part to the success of Robert Moses and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, using them to build new bridges and tunnels. A New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA), which could independently float their own bonds to raise capital, was founded and took over from the BOT in 1953. The BOT was dissolved.

The NYCTA, or TA as most refer to it, took over the projects underway. The South Brooklyn-Culver Line connection was finally opened in October 1954, almost 30 years after it was first proposed. In December, the connection between the White Plains Rd and Dyre Ave (former NY, W & B RR) opened, finally providing direct Manhattan service to the northeast Bronx. The 60th St Tunnel-Queens Blvd Line was opened a year later, and a year after that the Fulton St Line-Liberty Ave connection and Rockaway Lines were opened.

The TA was also able to begin rebuilding the DeKalb interlocking in Brooklyn (built between 1956 and 1961), and the greater Chrystie St Connection. Besides work on a new subway under Chrystie St (connecting the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges to the Broadway-Lafayette St station), the IND 6th Ave Line express tracks were connected, and a new station was built at 57th St/6th Ave to support the additional service. The entire work lasted a decade, and was the last project the TA completed before being absorbed into the larger Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1968.

In 1955, the city closed and began demolition of the 3rd Ave elevated from Lower Manhattan to 149th St in the Bronx. They claimed this was being done ahead of construction for the 2nd Ave Subway. But what no one realized was that the 2nd Ave Subway was never going to be built.

In 1956, during a TV interview, the new Chairman of the TA, Charles Patterson, was asked about subway expansion. He explained that there was no money for expansion. Puzzled, the host asked about the $500m bond act. Patterson replied that it had all gone to saving the system, which was close to collapse. City politicians were up in arms, and began to fight over the scraps of what was left in an effort to bring something to their boroughs. But there was no money for expansion, and there never was.

Devolution

The IND Second System was always a mirage. Each subsequent expansion plan seems to be a partial admission that the city was never really going to build as many new lines as promised. Many of these ideas were over the top to begin with, and many were needlessly redundant. When the systems were private, each expansion seemed to be more of a posture rather than a sound urban transit solution. Unification allowed cooler heads to prevail, and planners wisely shifted their focus to improving existing lines, adding more service rather than adding miles.

The myth of the Second System is that Robert Moses killed it when he was able to shift funding from the subways to highways. This isn’t an entirely false narrative, especially since he supported the 1948 fare increase and 1950 bond act because he knew it would provide him with more funds for expanding roads. The failure of the Second System has more to do with our society than just one person. The American consumer voted with their pocketbook, which was to purchase cars over taking transit.

The irony is that Robert Moses learned a thing from the subway builder, and used cars to beat transit at its own game. Moses used toll revenue from his bridges to finance debt to build more roads and bridges. But unlike the subway, which needed to maintain an entire railroad using a kneecapped fare, Moses only had to build a few crossings and could charge anything he wanted. It was much cheaper to maintain a bridge than a rail line. If a rail breaks, the network is down. If there is a pothole, cars can keep driving. It’s one of the advantages that roads have over rails. The cost to maintain the system is spread out over a larger base. Both transit and roads are subsidized by the public, but the benefits to the public tend to be greater with roads.

When it came time for public take over of transit systems, it was too late. The transit death spiral started sooner than most think; Robert Moses was just one of the first to take advantage of it. Moses had the power to build highways because the public supported him in doing so. He was of a generation that saw car ownership, and auto-centric lifestyles, as a progressive movement away from unhealthy urban areas.

This was not the end for far reaching expansion plans. The NYCTA kept a flame for the 2nd Ave Line, and worked on various proposals for a new East River tunnel. These were eventually folded into the Program for Action when the MTA took over in 1968. That is a story unto itself, but one which had the same problems and similar outcome of the previous plans.

Coda

Early streetcar and subway lines were built not so much to support existing demand, but to create new demand by opening up land just past the city core. But the private nature of these early transit companies meant that they were too focused on profits, not about service. There seems to be a misconception that we chose to dismantle perfectly good transit systems after World War II. In reality, these systems had been in a long decline due to deferred maintenance in favor of profit. The choice to drive over taking transit was a response to poor service.

American car consumption and driving exploded in the 1920 with the introduction of affordable, mass-produced cars. It was exactly when the New York City subways were being built and expanded that they were being undermined by the public choice to drive. Driving only made surface transit, both older streetcars and newer bus lines, worse. The desire to build new highways was a response to this demand, not the other way around.

Because the costs of running the subway have always been high, expansion has ended up on the chopping block when funds shrink. New York was not unique after World War II. Every US city had their own version of Robert Moses, and most thought that the benefits of a car-centric development pattern outweighed the costs of maintaining a transit system. Some at the time saw the limitations of this, but it wasn’t until a generation later when the general public began to realize what had been lost in the pursuit of progress.

Time and time again, leaders refused to understand just what it actually cost to run the system. Even today, in the midst of Congestion Pricing hearings, much of the riding public does not want to give one more cent to the MTA. And once again, not doing so will mean that the very system that keeps New York moving is in jeopardy of collapsing. The average rider only sees decrepit stations and late trains. Why should they have to pay more for such service? The unfortunate truth is that to really fix the subway, it would cost far more than anyone is realistically willing to pay. There will always be a tension between funding what we have and buying something new. Only when we are willing to be honest about the costs for both can we have our cake and eat it too.

Another excellent piece – and a really interesting read. You do an great job of “telling the story” beyond just maps and dates. Bravo!

Thank you!

I agree that this is a wonderful article. I think it is the existence of the station shells, such as at Utica Avenue and Fulton Street, that keep up the intrigue of what might have been with regard to the IND Second System. After all, they do still exist! It was also the legacy of the amount of construction of whole lines that was done around the Dual Contracts and the building of the IND that probably made people believe that the IND Second System would come into being, even though they could see the effects of Robert Moses and the Great Depression!

It really came down to budgets. The average person has no idea what a city or state budget looks like, not to mention an opaque state agency. The city, TA, and MTA have always played games to try and get more money. It’s a shame we don’t properly fund our transit in the US. But, at the same time, we spent much of the 20th Century investing in land use policies that directly led to the deterioration and abandonment of urban transit.