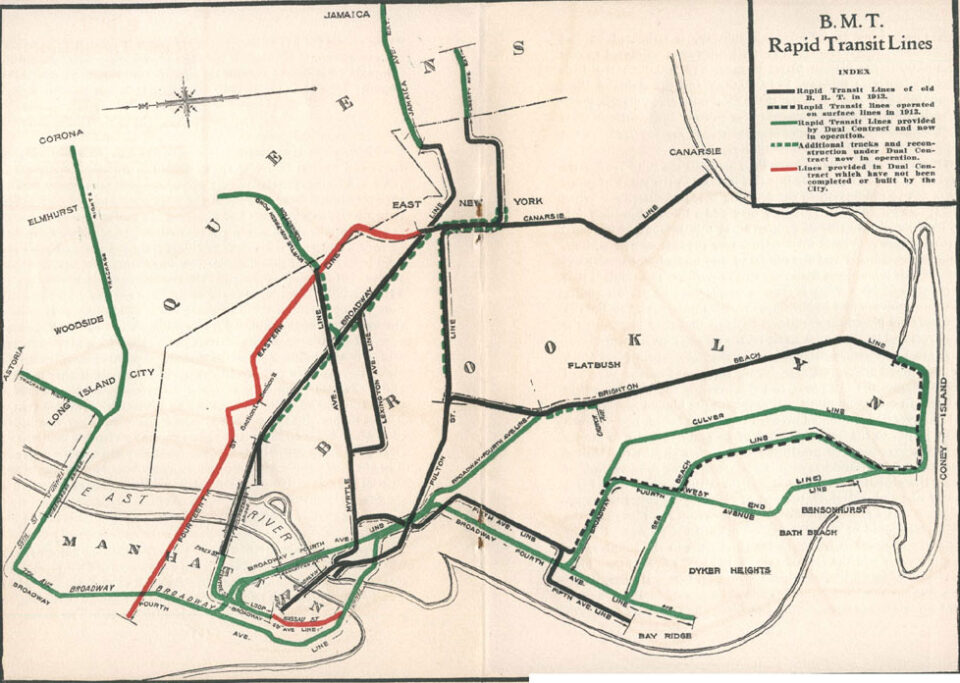

The subway lines which serve Williamsburg and Bushwick, the J/Z, M and L trains, were once part of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. Eastern Division. At the time, all most all trains began in downtown Brooklyn and fanned out. Trains either headed south, part of the Southern Division, or east, the Eastern Division. Covered in the last post, many of the elevated lines were torn down, either replaced by subways, or not. The City, through the IND Subway, planned to replace the remaining elevated lines, but lack of funds and the rise of the automobile ended those plans.

Historically, Williamsburg and Bushwick were immigrant working class neighborhoods full of heavy and light industry. After World War 2, these areas were hit particularly hard by white flight, and industry moving out of New York. Because of this, ridership was never as high as in other locations. When the city began extending subway station platforms in the 1950s, the stations along the L, J and M were not touched. Even today, subway lines which run through norther Brooklyn rank as the shortest in the city: C, L, J, and M trains are all 8-cars long, and the G is famously 4 or 5-cars.

As the City began to dig itself out of fiscal poverty in the 1980s, population, and with it, subway ridership, stabilized and rebounded. Areas of Lower Manhattan that had once felt like bombed out slums began to gentrify, bringing new residents and jobs. As rents rose, people began to look outside of Manhattan for more affordable housing. In the early 1990s, Williamsburg was a neighborhood most people had never heard of. 30 years later, it has become the poster child for gentrification, so much so that people refer to the cool areas of any random city as “the Williamsburg of…”

Ridership on the J/M/Z and L trains began to grow as well. The L was the first subway line to have Communication Based Train Control, CBTC, signals installed to made service more reliable and run more often. In 2010, the M train, which had always run to Chambers St and been extended to southern Brooklyn at rush-hour, was rerouted up 6th Ave using the Chrystie St Connection between the Williamsburg Bridge previously used by the KK train. This shift acknowledged the ridership shift to Midtown from Lower Manhattan that had begun after World War 2.

While ridership growth has occurred at all stations, the stops closest to Manhattan see the highest ridership. Major transfer stations such as Myrtle-Wyckoff on the M and L, and Broadway Junction on the A/C, J/Z and L see the highest ridership. These nodes distribute riders from further out in Brooklyn and Queens, and serve a secondary network of commuters not heading to Manhattan. Broadway Junction is a major dividing line between riders heading to Brooklyn and Manhattan, and riders heading to Jamaica or JFK Airport.

Ridership on these lines is still somewhat unbalanced. Ridership on the BMT Canarsie Line, L train, is far higher than on the Jamaica Line, J/Z, or Myrtle Line, M train. This is due to the L providing a more direct route into Manhattan along 14th St. While the M provides direct service to 6th Ave, this is a recent routing. Until 2010, all J/Z and M trains served Chambers and Broad Sts downtown. Growth along the L train fed on itself, and it has only recently spilled over to the J/Z and M train corridors.

Ridership on the BMT Jamaica Line between Marcy Ave and Broadway Junction has seen a higher level of growth due to gentrification in Williamsburg, Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant. Ridership between Marcy Ave and Broadway Junction is higher overall than stations in East New York and Queens, which have been slower to develop. Additionally, Broadway Junction forms a de facto border between work shed areas: riders to the west are more likely heading to Manhattan, while riders to the east are more likely heading into Queens, though many still are going to Manhattan. Part of this imbalance could also be the more suburban, autocentric nature of Queens compared to central Brooklyn.

The ideas outlined in this post were originally developed as part of a larger report on deinterlining I was working on in 2019 and 2020. At this time, subway ridership had peaked and was slowly declining. This was due in no small part to maintenance issues causing cascading problems throughout the system. But this was seen as a bump in the road in terms of ridership growth. The COVID-19 pandemic changed the equation. Ridership plummeted and, while has been growing ever since, hybrid and remote work has kept overall ridership about 1/3rd lower than pre-pandemic levels. The capacity issues that were once blocking growth are now less important than they were, but are still present nonetheless. Therefore, the purpose of this post is not to propose changes that are needed now, but to point out the issues as they exist and propose solutions for when the time comes.

Description of the Eastern Division Lines

The Canarsie Line serves only the L train. It is a 2-track line running from 8th Ave and 14th St in Manhattan, across the East River to Brooklyn. In Brooklyn, it weaves through Williamsburg and Bushwick, passing briefly into Queens, before turning south to Broadway Junction. The line is entirely underground until the Wilson Av station, where the southbound track comes above ground before descending underground again. The line rises above ground before Broadway Junction and continues elevated through East New York to Canarsie. The last two stations are built at grade, and the terminal at Rockaway Parkway features the only train-to-bus transfer within the fare area.

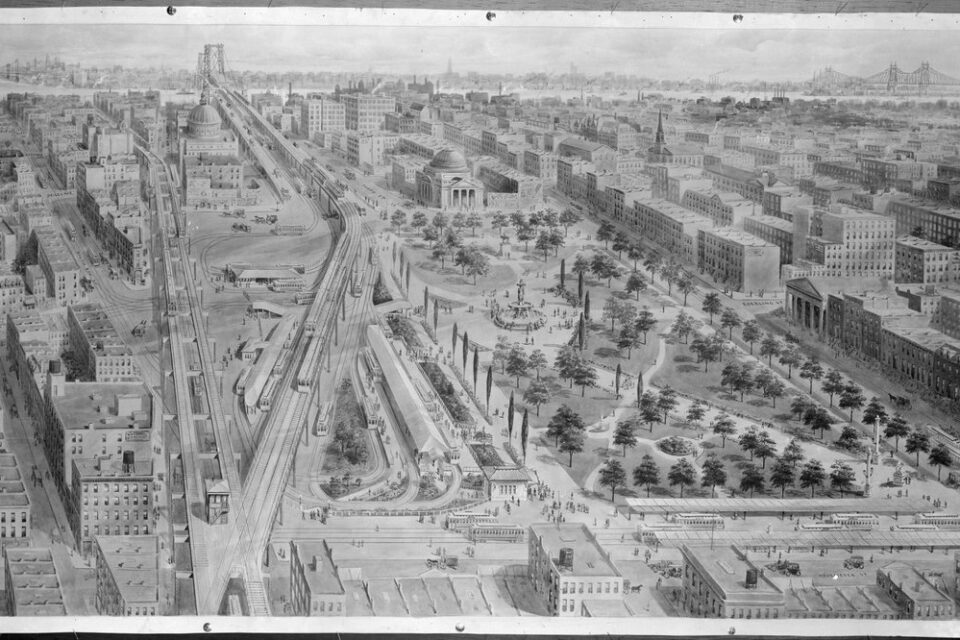

The Jamaica Line is a complex collection of different lines which were built at different times. The original 2-track elevated line ran from Broadway and the East River ferry in Williamsburg, along Broadway to Broadway Junction (which wasn’t the original name of the station). It was extended along Fulton St to Crescent St, turning north to a terminal at Jamaica Ave. The Jamaica Line was connected to the new Williamsburg Bridge when it opened in 1908 (though the bridge had opened 5 years prior), extending over to an underground terminal at Essex and Delancey Sts.

The Myrtle Line branches off the Jamaica Line at Myrtle Ave and Broadway, running elevated to Metropolitan Ave in Middle Village. This line once continued along Myrtle Ave to downtown Brooklyn, crossing the Brooklyn Bridge and terminating at Park Row. The 2-track line also featured a branch along Lexington Ave that connected to the Jamaica Line. Originally, the Myrtle Line elevated tracks ended at Wyckoff Ave, after which a ramp led to street level and the line continued north to Metropolitan Ave at-grade.

During the Dual Contracts era of subway expansion, both lines were upgraded and extended. The Jamaica Line was extended to Lower Manhattan via the Centre St Subway, a 4-track line that was designed to allow elevated trains from Brooklyn to loop back through Lower Manhattan. The elevated structure from Myrtle Ave to Broadway Junction were reinforced and a middle track was added for express service. The line was extended east along Jamaica Ave to 168th St in Jamaica Center. This extension was built with 2-tracks, but had space and provisions for a middle track to be added later. The Myrtle Line was connected directly to the Jamaica Line at Broadway, and a middle track was added between Broadway and Wyckoff Ave (this track was never used for express service, but was used for storage until it was eventually removed.) Finally, the elevated tracks were extended to Metropolitan Ave.

The track structure between Broadway Junction and Crescent St was not upgraded, as had been done to the west. To get around this, the BRT proposed building a middle track above the platforms and tracks, as was common on the elevated lines in Manhattan. At Alabama Av station, there exists a ramp with no tracks for the continuation of the express track. However, it is claimed that engineering reports from the 1950s show that the structure could not handle such an addition. While I have not seen this report myself, I will err on the side of its authenticity.

The Jamaica Line saw two more extensions in its lifetime. The plans for a subway loop in Lower Manhattan were delayed due to the difficulty of building lines under the narrow colonial-era streets near Wall St. The Broad St Line was finally opened in 1931 (though operated by the BMT, it was built by the IND), finally allowing J trains to loop back into Brooklyn through the Montague St Tunnel. Over the years the J, in some form, has served the Brighton Beach and 4th Ave Lines, while the M has served the Brighton Beach and West End Lines. In Jamaica, the Archer Ave Lines rerouted the elevated Jamaica Line (from 121st St to 168th St) into a subway to Parsons Blvd.

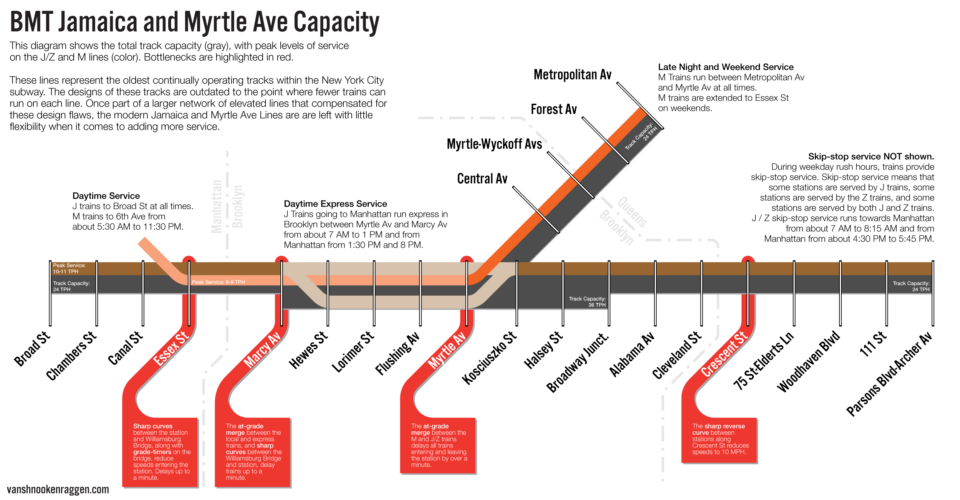

Service, and Bottlenecks

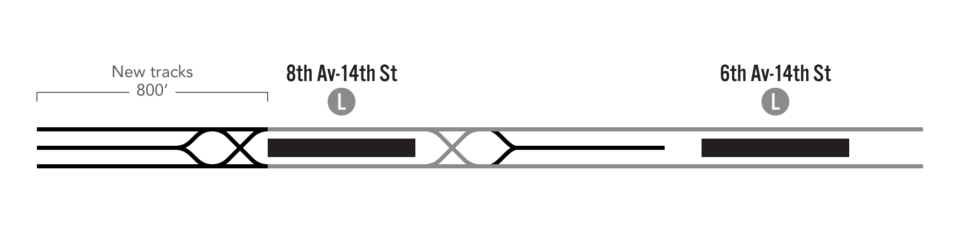

Because the Canarsie Line has only one train line, the L, service is reliable and frequent. The line is capable of running 24 trains per hour (TPH), and does at rush hours. At night, service is anywhere between 20-25 min between trains. The line has a third track for storage between 8th and 6th Aves, and between Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs and Halsey St. Drop-outs at Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs are common during mid-day service. The line has access to two yards, the East New York Yard at Broadway Junction, and the Canarsie Yard, between East 105th St and Rockaway Parkway.

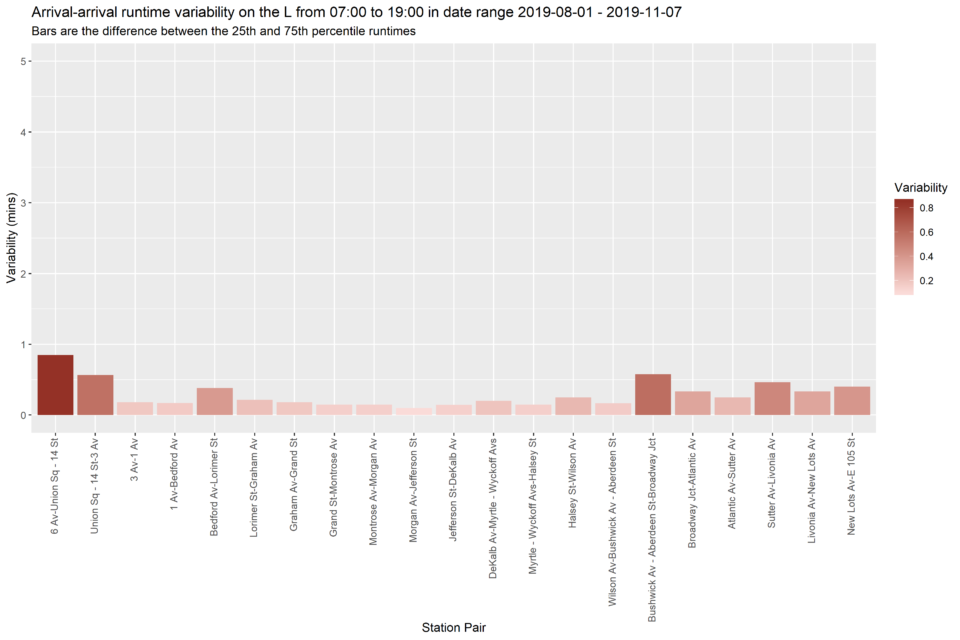

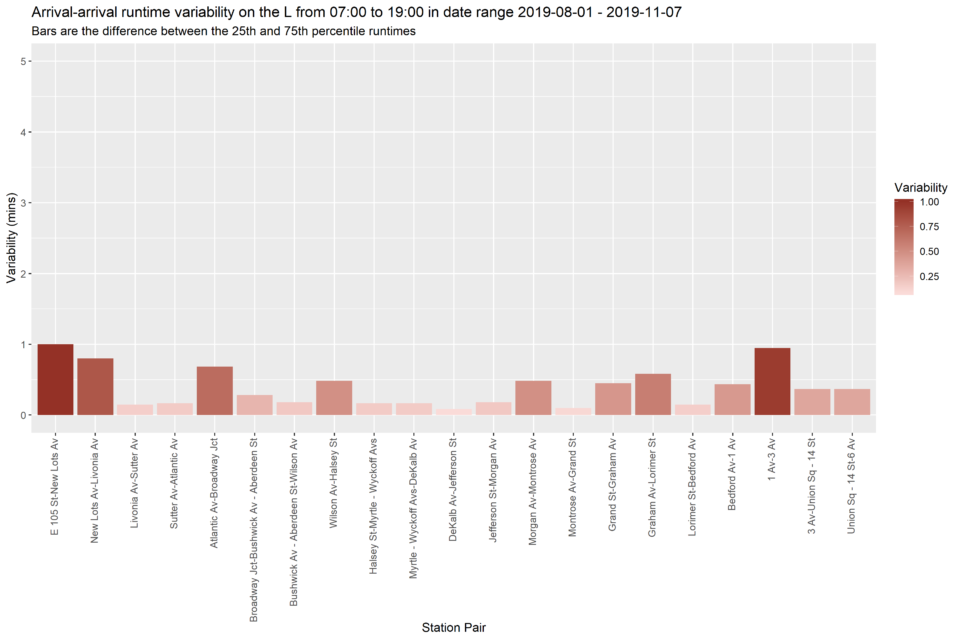

Because the L does not interline (share tracks) with any other service, delays come down to station congestion and non-revenue movements. The primary bottlenecks are between 8th Ave and 1st Ave where ridership is highest, often delaying trains in the station, and where in-service trains must wait for trains being taken out of service at Broadway Junction and East 105ht St. Some trains even start at East 105th St station rather than at Rockaway Parkway because trains must back out of the yard and reverse to pull into Rockaway Parkway.

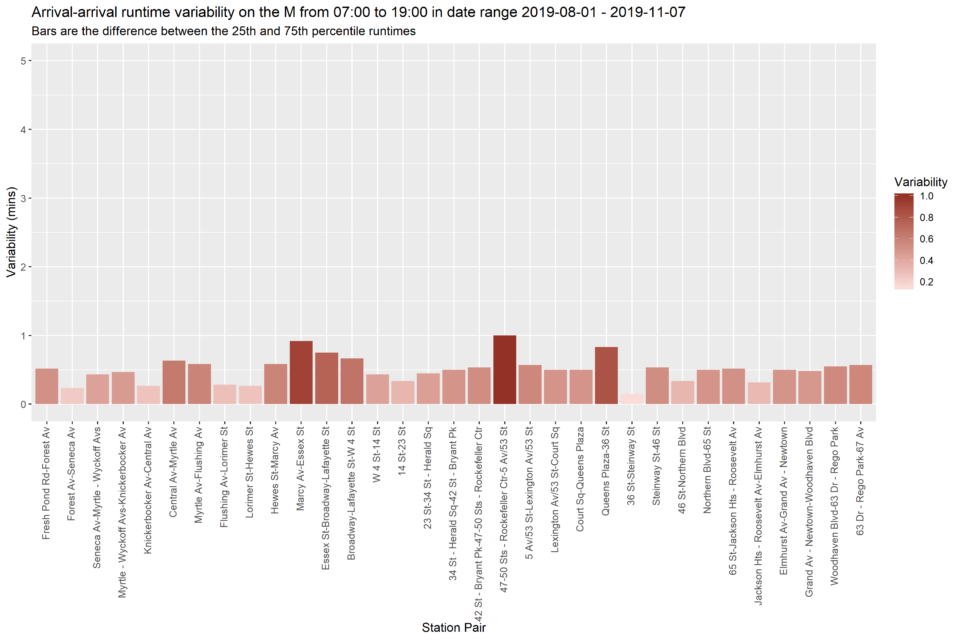

The Jamaica and Myrtle Lines, on the other hand, contain a number of bottlenecks which limit overall service. J trains run between Broad St in Lower Manhattan and Parsons Blvd in Jamaica at all times. At rush hour, J trains run express between Marcy Ave and Myrtle Ave in peak directions. Also at rush hour, skip-stop service is utilized. The J and Z trains trade off at stations between Myrtle and Parsons Blvd. Trains alternate stops, usually stopping at every other station. A select few stations are served by both the J and Z trains. M trains are added to the mix, connecting to the line at Essex-Delancey Sts and splitting off at Myrtle Av. The M only runs local, and only runs to Manhattan during the day. At night, it runs as a shuttle between Metropolitan Av and Mrytle Av-Broadway. During the weekend, M trains are extended to Essex-Delancey Sts.

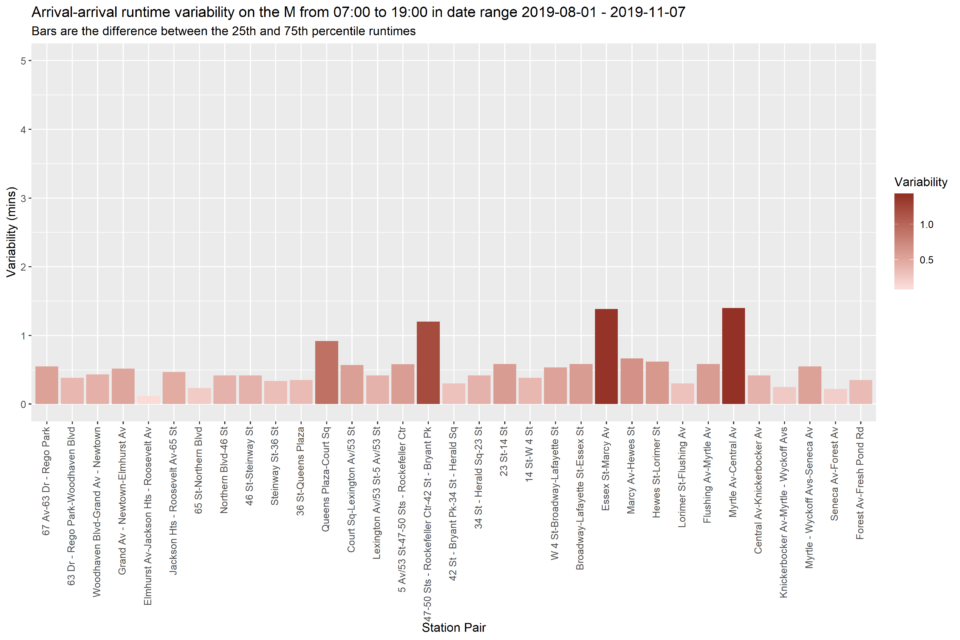

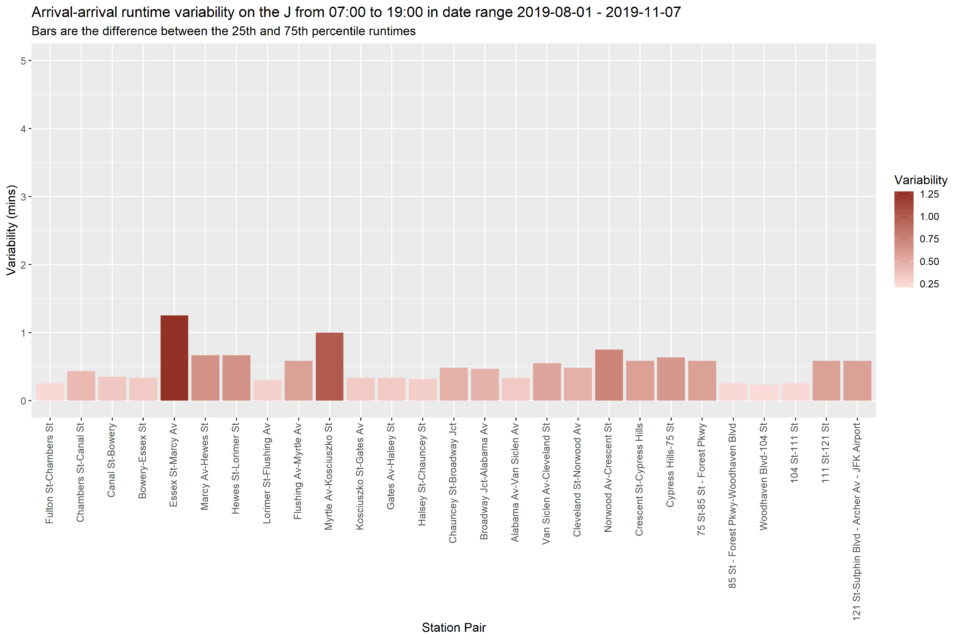

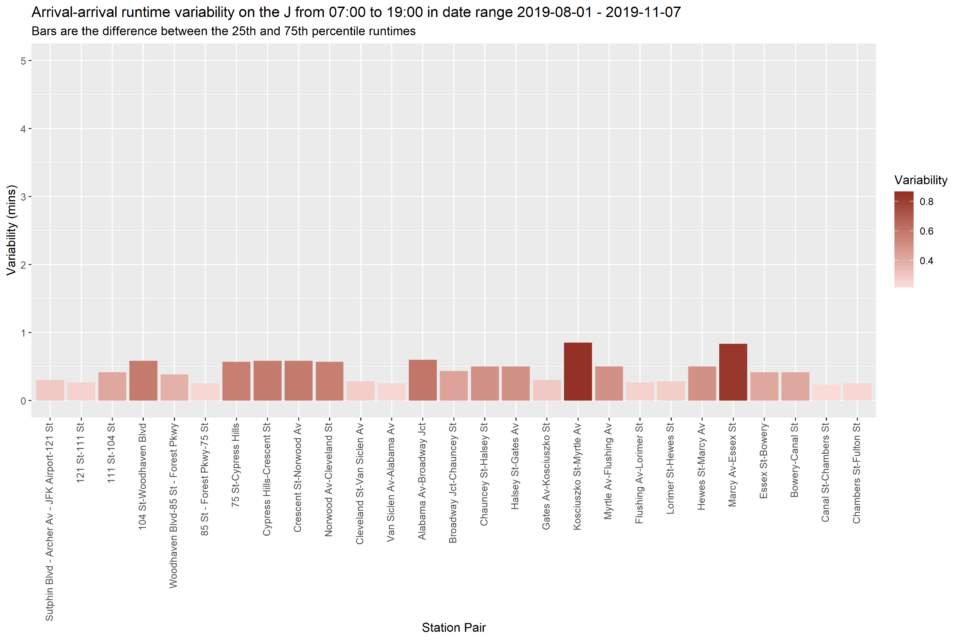

The interlining of local, express, and skip stop services all create delays from merging trains. But the tracks themselves present the larger issue. Major bottlenecks include:

- Reduction of 3 to 2 tracks between Essex St and the Williamsburg Bridge

- A sharp reverse track curve entering Essex St station

- Grade timers (speed restrictions) on the Williamsburg Bridge

- Sharp curves between the Williamsburg Bridge and Marcy Av station

- Local-to-express merge after Marcy Av station

- Flat, at grade junction between Jamaica Line and Myrtle Line at Myrtle-Broadway

- Sharp curve on Myrtle Line connecting tracks at Broadway

- Speed restrictions on elevated tracks between Alabama Av and Crescent St

- Sharp reverse curve between Crescent St and Cypress Hills stations

- Poor switch location at Parsons Blvd terminal

The speed restrictions over the Williamsburg Bridge are related to a bad crash that occurred in 1995, which injured 45 riders and killed the motorman. The NTSB found that the crash was primarily due to human error; the motorman was fatigued after an 8-hour shift. The MTA determined that the signal blocks on the bridge were spaced too close together, meaning that trains were allowed to operate closer to one another. They spaced the blocks further apart and placed grade timers on the signals, which would stop the trains if they went too far over the limit.

This is probably one restriction which, for the sake of safety, won’t be changed. But the MTA was famous for using grade timers like duct tape all over the system. Instead of paying to replace the aging signal system, they simply slowed trains down all over. This network wide slow down literally impacts capacity because it reduces how many trains can cycle through per hour. One of the positive lasting impacts from Andy Byford’s short tenure was the creation of a task force that goes line by line to find timers that can be removed, thus speeding service and increasing capacity.

This is a relatively cheap fix. But the age of the Jamaica and Myrtle elevated track structures still limits speeds. Additionally, the poor interlocking and curve designs along the line are real hindrances to speed and capacity. Upgrading signals is relatively simple, but only more expensive solutions to the physical bottlenecks will truly open up the capacity potential of these lines.

Phase 1

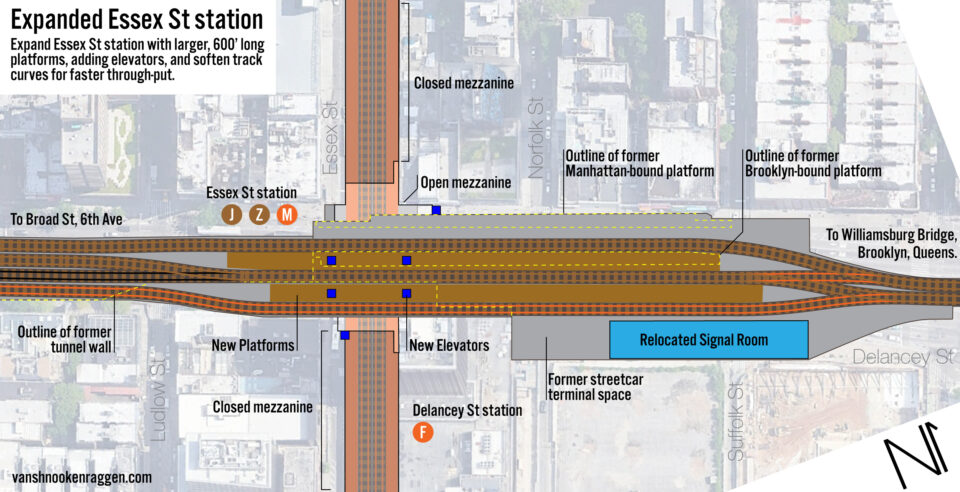

Expand Essex St station

The second most detrimental issue facing the Jamaica and Myrtle Lines is located at the Essex St station. Essex St station was originally built as a 3-track terminal for elevated trains coming from Brooklyn. The terminal was built on the north side of Delancey St, while a second terminal for streetcars was built on the south side. This required the Broad St-bound track to have a sharp curve as it enters the station. This track was softened a bit, leaving a small portion of abandoned platform at the far end of the northern platform.

When the Chrystie St Connection was opened in 1968, 6th Ave local trains were directly connected to the Essex St station. This creates a merge, which is a source of delays. However, the 3-track layout makes this merge more manageable, as it allows M trains to enter the station on the southern track, while J trains enter on the middle track. The delay occurs when there are two trains in the station, and one must wait for the other to leave first.

Rebuilding Essex St station will not fix this merge, but it would allow the sharp curve to be removed, and it would allow the station to be extended for 600′ trains. Extending all Jamaica Line platforms to hold 10-car, 600′ trains is not necessary for Phase 1, but extending all stations at which the M train stops should be. The M train runs along the 6th Ave and Queens Blvd Lines, which have much heavier traffic. But the shorter trains reduce capacity on the M by 25%. Essex St would be the only underground station that would need to see such an extension for longer M trains, making it a cheaper first step.

What makes expanding Essex St station more practical is that much of the underground area which it would need to expand into is already open. The long abandoned streetcar terminal has been sitting vacant for decades. The MTA has used some of this space for back-of-house facilities, but these can be moved to parts of the vacant terminal that are away from where the new platform would go.

The northern platform and current southbound track would be abandoned. The current middle track would replace the southbound track. The existing Brooklyn-bound platform would be expanded over the Brooklyn-bound track, creating a platform that is now ADA compliant with space for elevators to the lower level. This platform would be the new southbound platform. The new Brooklyn-bound platform and track would be built through the vacant streetcar terminal, as well as require excavation between Ludlow and Norfolk Streets.

The tracks entering and leaving the stations would be shifted to reduce their curve radii. The station would function the same as it does now. While speeds over the Williamsburg Bridge might not be increased, trains can enter the station at higher speeds, increasing throughput.

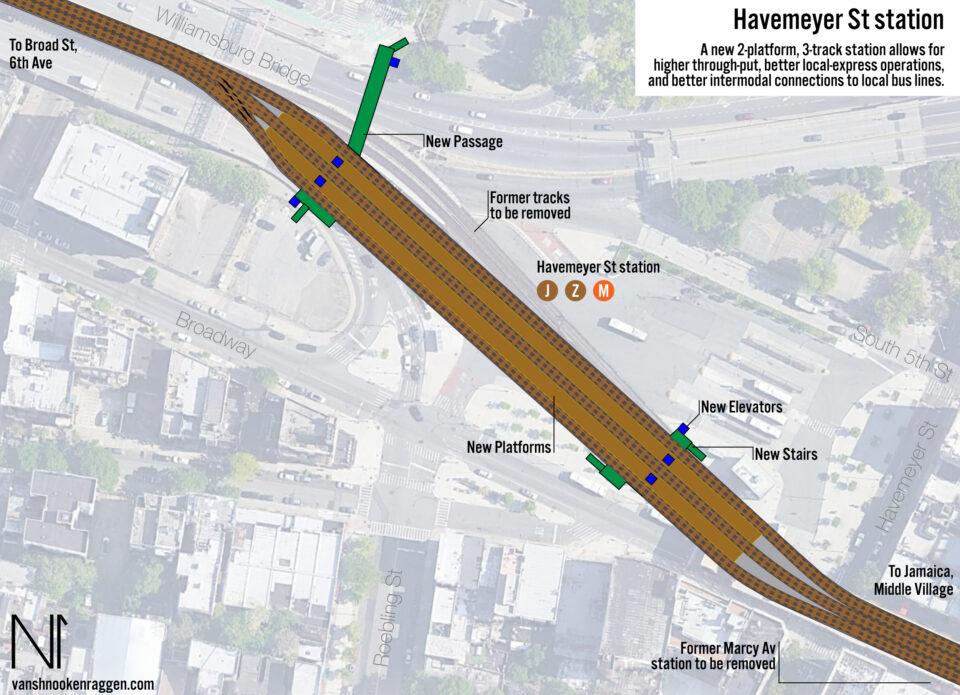

New Havemeyer St station

After the Williamsburg Bridge opened, the elevated tracks that ran along Broadway to the East River were connected directly to the bridge with an 800′ S-curve structure. Thankfully, these curves are much more forgiving on speed. But trains still must slow down between the bridge and Marcy Av station. East of Marcy Av station, trains merge to and from the express track, forcing local trains behind them to stop. This means that there are three slow spots: the first curve, the second curve, and the station. What if we could combine them into only one?

If there was a 3-track station built at the point of the curve, or rather, on the straight track between the two curves, the delays would be negated. Instead of creeping into and out of the station, trains would simply slow to stop as they would at any other station. Softer curves at either end of the station would improve speeds when trains enter and leave the stations. A new middle track would be added to allow express trains to split or merge without backing up local traffic behind them. The new station would have the added benefit of being located directly above the Williamsburg Bus Plaza, opening the door for better multi-modal transfers. The station could have a passage built crossing over the bridge roadbed to South 5th Pl, providing better access to residents north of the bridge.

Building this station while keeping existing trains running would be tricky, but not impossible. The Brooklyn-bound track and platform would be built first, connecting to the bridge tracks and Broadway elevated. All service would shift to these two tracks while the existing track structure is removed. Then the Manhattan-bound platform and track would be added. The Marcy Av station would be removed.

Like the expanded Essex St station, the new Havemeyer St station would feature 600′ platforms and be ADA accessible.

Williamsburg Bridge station?

With the continued development of the Williamsburg waterfront with high-density residential buildings, some have suggested that a station on the Williamsburg Bridge be added. I’ve heard conflicting reports that elevated trains once stopped at the Manhattan anchorage, which was accessible by elevators. However, I’ve never seen this confirmed. There were no stations planned or built on the bridge, on either side. In fact, the grade on either side of the bridge is too steep for an ADA-compliant station to be built. The tracks between anchorages are flatter, but without a major redesign of the bridge, it would not be feasible to add a station here.

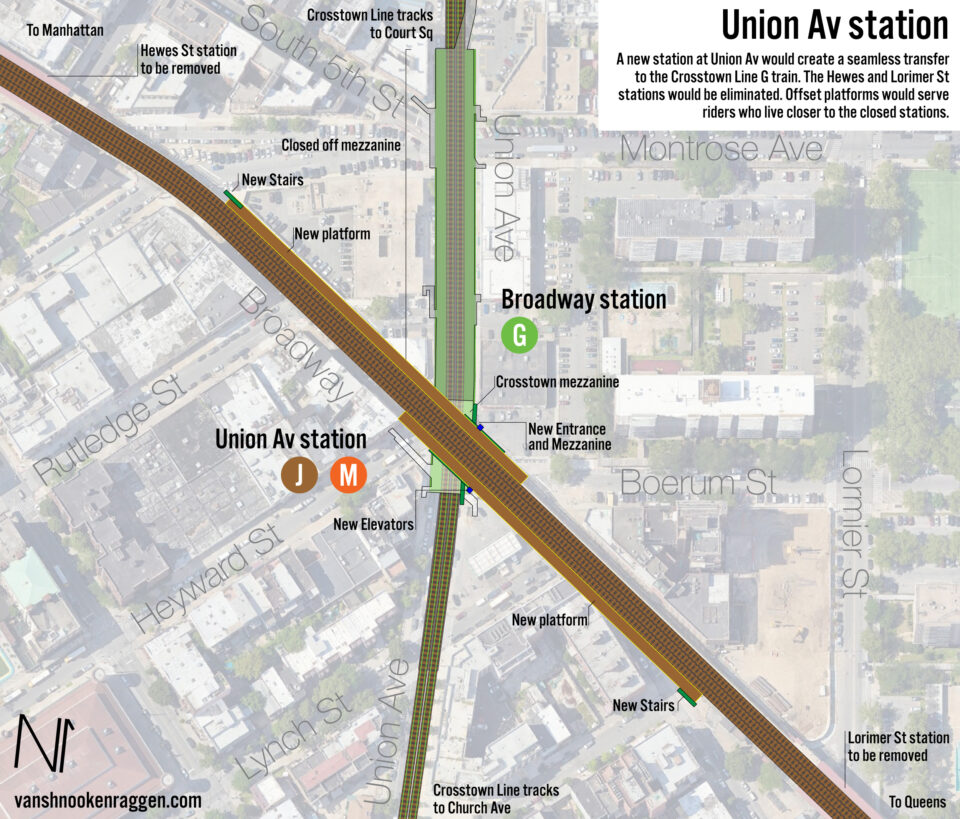

New Union St station

When one looks at a subway map of Williamsburg, you will notice that the J/Z and M trains pass right by the Crosstown G train without stopping, while the G provides a transfer to the L train at the next stop. The lack of a transfer between the Jamaica/Myrtle Lines and the Crosstown Line is no mistake. When the IND built the Crosstown Line in the 1930s, it did so with future ambitions to replace the Jamaica and Myrtle elevated lines with subway tunnels. Perhaps one day a new line will be needed. But with construction costs being as high as they are, rehabilitating existing lines to get more out of them is the preferred alternative. Providing a free transfer between the J/Z, M and G trains would be an investment that would reduce crowding on the L and increase ridership on the J/Z and M.

The most affordable connection would be to provide a free out-of-system transfer with the new OMNY fare system. This was done with Metro Cards during the reconstruction of the Canarsie Tubes. However, the closest Jamaica Line stations to the Crosstown Line are both over a 600′ walk away. This is not the most pleasant of urban streetscapes either. This type of transfer is less attractive for a healthy individual, and worse for those needing wheelchairs or canes.

Relative to other Jamaica Line stations, the Hewes St and Lorimer St stations have low ridership. It is therefore recommended to combine both stations with a new station above Union Ave that will provide an in-system, accessible transfer between the J/Z, M and G trains. The platforms would be offset, so that there is one entrance closer to the old Hewes St station and one closer to the old Lorimer St station. Lorimer St station also serves the B48 bus, which runs a north-south crosstown route. This route could be adjusted so that it runs up Union Ave before turning down Montrose Ave (or back on Boerum St) to get back to Lorimer St.

Combining two stations into a new transfer stop would further speed up local trains, while also increasing ridership. Running one station is cheaper than two. Like the previous stations, the Union Av station would be 600′ long and be ADA accessible.

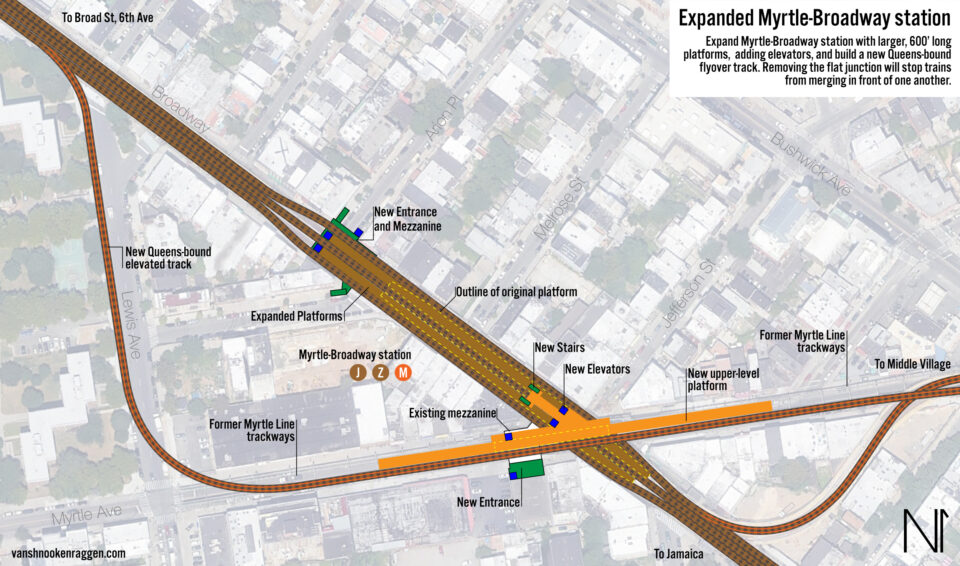

Expand Myrtle-Broadway

If Essex St is the second worst issue on the Jamaica and Myrtle Lines, Myrtle-Broadway is the first. These days, the MTA calls this station simply “Myrtle Av”, but I will use the longer name to avoid confusion. This would be the worst junction in the entire subway if it wasn’t for the Rogers Junction (also known as Nostrand Junction) on the IRT Eastern Parkway Line. Myrtle-Broadway features a flat junction, where M trains must pass in front of all local and express Jamaica trains. Worse, the curve between the Jamaica Line and Myrtle Line is very tight.

To complicate matters, when J/Z trains run express on the Jamaica Line, they only do so between Marcy Av and Myrtle Av stations. So local trains must also wait while express J trains merge back on the local track. This may seem strange given that the express track extends to Broadway Junction, but ridership on the local stations between Myrtle Av and Broadway Junction is relatively high, meaning that the extra service is necessary. With three tracks, it should be possible to use different tracks to limit merge delays. But express trains foul this up.

Visiting Myrtle-Broadway, you notice immediately a large structure hanging over the station. This is the former Broadway platform and trackways of the original Myrtle Line. Initially, the lines were separate, though transfers were provided. The connection was built during the Dual Contracts, and actually increased service to Metropolitan Av since capacity on the Myrtle Line was limited due to it sharing tracks with the BRT Lexington Ave Line. As part of the Dual Contracts, the track structure and stations along the Bushwick and Ridgewood portion of the Myrtle Line were upgraded and expanded for subway service, but all stations west of Broadway remained smaller and lighter for the wooden elevated trains. Service on the downtown portion ended in 1969, and it was soon torn down. The MTA saw the line as too expensive to rehabilitate, and many locals wanted to see the elevated line removed to improve property values.

The structure that remains at the Myrtle-Broadway station does so because it is necessary to keep the station standing. The entire complex was engineered together, so removing the abandoned sections would require strengthening others. All together, it’s an expense the MTA never viewed as essential.

This structure offers an interesting solution for the Myrtle-Broadway junction. It’s only the Queens-bound M trains which pass in front of other trains. Therefore, it is only the Queens-bound track which needs to be relocated. Chicago recently rebuilt a similar junction between the Brown Line and Red/Purple Lines at Belmont. The new Belmont fly-over required the demolition of a number of buildings, even though the alleyways of Chicago provide more room to work. In Brooklyn, the Myrtle track connection took over a number of back yards, and the local residential streets that run along Broadway are not suitable for running new elevated lines along.

The solution comes on the other side of Broadway. A new Queens-bound track would branch off from Broadway along Lewis Ave, then curve onto Myrtle Ave, connecting to the upper level of the Myrtle-Broadway station. Queens-bound M trains would use this track, and stop at a rebuilt and expanded upper level platform. They would then use the existing trackways to continue on to Metropolitan Av. Manhattan-bound M trains would continue to use the existing connection, though the curves could be softened a bit since only one track is needed.

The entire structure would need to be heavily reinforced, but this could be an opportunity to remove unneeded supports and bring more light onto the street. As before, the platforms would need to be extended to hold 600′ trains. This would be accomplished by extending the station westward, adding a new entrance at Arion Pl/Stockton St, and replacing the existing entrance with a new ADA compliant head house on Myrtle Ave, possibly using an existing power substation building. The longer trains would use more power, so it may make sense to simply repalce this substation with a larger one, allowing the space to be reused. The upper level station would only use the Queens-bound track way, leaving the former downtown Brooklyn-bound track way open for platform space and direct access to the lower level platform.

Late night, M trains run as a shuttle between Myrtle-Broadway and Metropolitan Av. This would likely continue, which means that access to the existing middle track would remain. Service levels late at night are such that merging trains don’t cause delays. But this would mean that the upper level would need to be taken out of service, requiring extra work for station agents to do so.

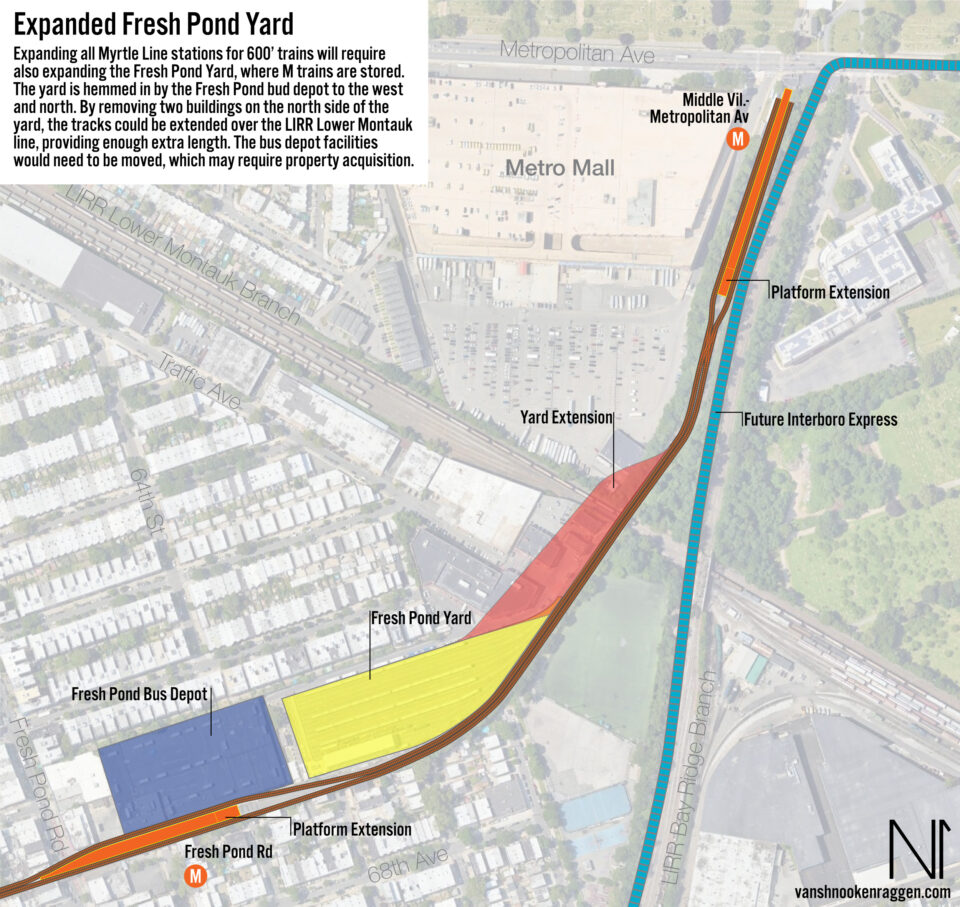

10-car Myrtle Line platforms and Fresh Pond Yard expansion

The final section of Phase 1 would be to extend the remaining Myrtle Line station platforms to accommodate 600′ trains. The Central Av, Knickerbocker Av, and Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs stations were rebuilt during the Dual Contracts and have enough space for such extensions. The Seneca Av and Forest Av stations are more hemmed in, threading through homes built close to the tracks. Platform extensions at these stations are possible, though they may require slight track readjustments. Fresh Pond Rd station has more than enough space to the east for an extension.

The final stop, Middle Village-Metropolitan Av would need to be extended further south, straightened out, and have a new double crossover switch installed. The north end of the platform should be moved about a dozen feet to the south to allow slack track at the end of the line. This slack allows trains to enter the station at slightly higher speeds, giving the train just enough space so that it does not slam into the bumper blocks.

The last consideration is the Fresh Pond Yard. The M train utilized the Fresh Pond Yard in Ridgewood and the Jamaica Yard in Kew Gardens. The Jamaica Yard, built by the IND, easily handles 600′ and longer trains. But the Fresh Pond Yard, built by the BRT, can only hold 480′ trains (and not every track in the yard can handle trains this long either.) Directly to the west of the yard is the Fresh Pond Depot, a large bus maintenance facility. To the north of the yard are other maintenance buildings for the depot. If these can be moved, then it would be possible to expand the yard to the north, across the LIRR Lower Montaunk Line.

Phase 1 Service Improvements

Current max-frequency on the J/Z at rush hour is 11.5 TPH, while frequency on the M is 8.5 TPH. Combined, 20 TPH runs over the Williamsburg Bridge, but not east of Myrtle-Broadway. Removal of these bottlenecks should allow for an increase of 4 TPH. M trains are limited by the Forest Hills-71 Av terminal. I outlined the issues with this terminal in a previous post. The extra capacity would be added to J/Z service. This is why it’s so important to extend M train station platforms, but less so for J/Z platforms. With existing 8-car trains and levels of service, 77,740 passengers per hour (PPH) can cross the Williamsburg Bridge in both directions at peak times. With 10-car M trains and more frequent J/Z trains, 101,676 PPH can cross, an increase of 30.8%.

Phase 1 improvements would be one of the best value investments the subway system could make. It’s hard to calculate exactly how much these improvements would cost. But based on costs taken from the MTA 2015-2019 Capital Program (and adjusting for inflation), a very back-of-the-envelope calculation for the entire phase would cost $1.5 billion. Most of this cost would be associated with expanding Essex St station, since it would require excavation, the Myrtle-Broadway expansion, and the Fresh Pond Yard extension. This estimate does not include new rolling stock.

CBTC is not planned to be installed on the Jamaica and Myrtle Lines any time soon. It should be installed, if it hasn’t already, as part of Phase 1. More reliable signals and higher speeds are surely welcome. But CBTC can’t fix the very real physical bottlenecks that currently exist.

Phase 2

10-car L trains and Canarsie Yard expansion

Like the Jamaica and Myrtle Line platforms, the Canarsie Line has stations only long enough for 8-car trains. Given the growth in ridership on the L train over the last two decades, it may seem odd that extending Canarsie Line platforms is in the second phase, but this is due to the investments previously made on the L. The L has modern CBTC signals which, in theory, allow over 30 TPH. What the service ceiling is will be based on a number of factors, but with current operations, the L train currently runs 24 TPH. With more efficient operations at 8th Ave and Rockaway Parkway, it may be possible to hit 30 TPH.

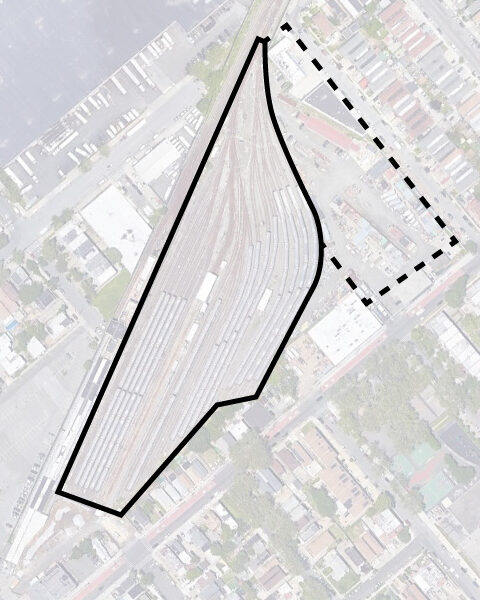

Another reason to focus on the Myrtle Line first is that the upgrades proposed are far cheaper relative to the increase in passenger capacity. For Phase 1, only one station is underground. The L train, on the other hand, has 17 underground stations and 7 above ground stations. If every L train station platform is extended to hold 10-car trains, the back-of-the-envelope cost estimate is $3.3 billion, not including yard expansion. The Canarsie Yard is constrained as well, and would require property acquisition on the northeast corner to allow for longer storage tracks.

Terminal Operation Delays

The main source of delays on the L are at either end of the line, where trains terminate. The 8th Av terminal features bumper blocks at the immediate end of the station. This means that there is no room for error when a train pulls into the station; the train can not over shoot the platform and be fine. Trains must enter the station slowly to not crash. There is a layup track between 8th Av and 6th Av stations. Most trains do not use this track, but in the case that one does, it will delay trains entering and exiting the 8th Av station. Because this is not a normal procedure, it does not warrant any large scale changes.

Should the Canarsie Line see platform extensions, it would be valuable to provide extra track space west of the station. Leaving enough space for trains to enter at higher speeds would be good. But providing layup tracks would be better, though more expensive. At the new Hudson Yard-34th St station on the 7 train, layup tracks were built south of the station, long enough to hold up to 6 trains, including 2 more within the station. This extra storage allows terminating trains to clear the station after they are fumigated quicker than going back into service. They allow just enough extra flexibility so that the additional track capacity that CBTC provides can be used.

The 7 train layup tracks are about 2,000′ long. If the same length of tracks were to be built at 14th St, the tunnel would extend into the Hudson River. A workaround would be to build three tracks, each extending to 9th Ave. This, along with a new switch, would provide enough slack to boost throughput above 30 TPH.

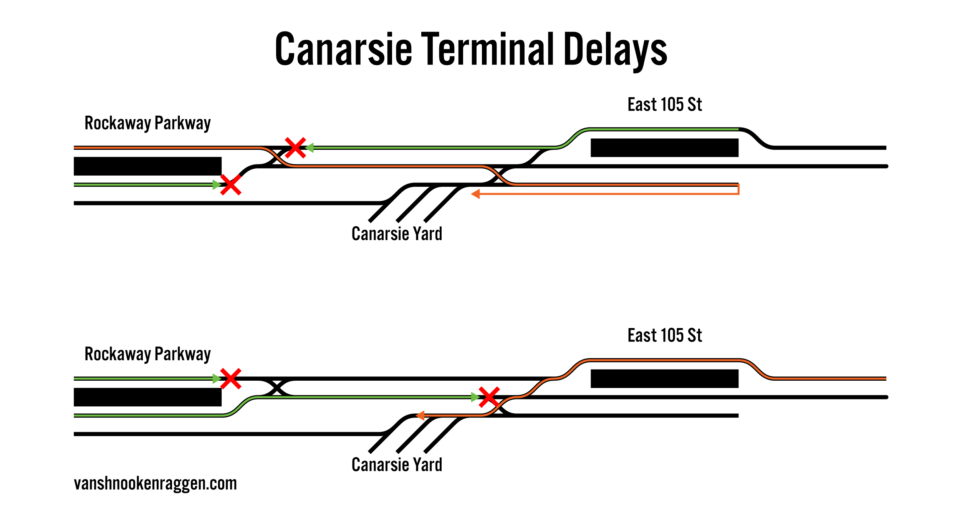

At the other end, the Rockaway Parkway terminal is a more acute problem. The terminal is built adjacent to the Canarsie Yard. This yard is the primary storage yard for the L train. The yard is only storage, so L trains are often deadheaded up to Atlantic Ave where they can access the East New York maintenance facility.

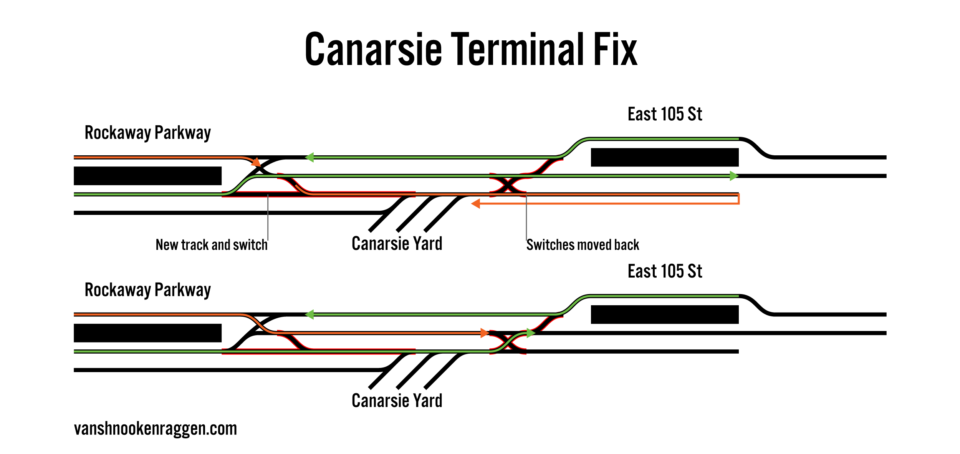

The issue at Rockaway Parkway is that when trains are done with their run, they must deadhead up to East 105 St station and reverse onto a layup track. While doing so, trains must pass directly in front of in-service trains. Often, trains are pulled into service at East 105 St so they don’t have to make this extra move. But trains are also pulled out of service at East 105 St, blocking trains at Rockaway Parkway.

A simple solution to this is the addition of one new track and switch, directly connecting Rockaway Parkway to the layup track. While trains will still need to pass in front of one another, the time spent on the in-service Manhattan-bound track. The existing Manhattan-bound track could also be used for quickly moving trains out of the terminal, while the new track allows Manhattan-bound trains to bypass the out-of-service train.

Rockaway Parkway is a very cramped terminal for trains. At modern terminals, similar movements would be made on grade separated tracks. The Rockaway Parkway station is only 900′ south of East 105 St, meaning there is virtually no room to build a flyover track. Worse, the line is hemmed in on both sides by development.

In order to boost service levels above what they are now, another terminal is needed. Currently, the only other station on the Canarsie Line which is used for short-turning trains is Myrtle-Wyckoff Avs. East of this station is a layup track that can currently hold 3 trains. Should the Canarsie Line start using 600′ trains, this would be reduced to space for 2 trains. Myrtle-Wyckoff is a less than ideal place to turn trains, since many riders out in Ridgewood and Bushwick are heading to Broadway Junction. Ridership drops off after Broadway Junction, but Halsey, Wilson, and Bushwick-Aberdeen Sts have seen dramatic ridership growth as this end of Bushwick gentrifies.

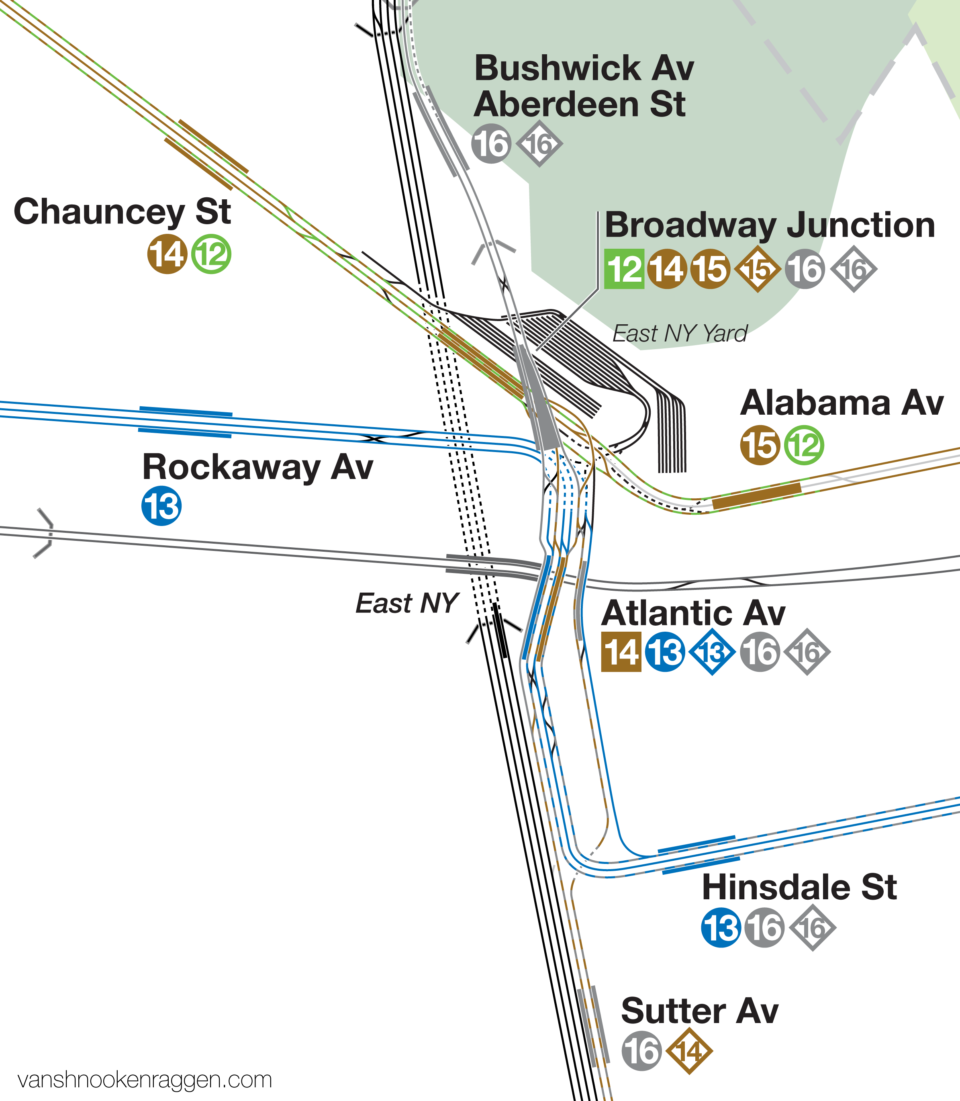

If one travels to the Broadway Junction area today, you will see one of the most complex webs of elevated track in the entire system. What’s impressive is that this is less than it used to be. Broadway Junction once hosted an additional elevated line, the Fulton St El, which was replaced by the A/C subway. When it was elevated, the tracks were designed in such a way that trains from different lines could reverse branch up other lines. When the Fulton St El was demolished in 1958, much of the connecting tracks were removed. However, some remained, and could be useful.

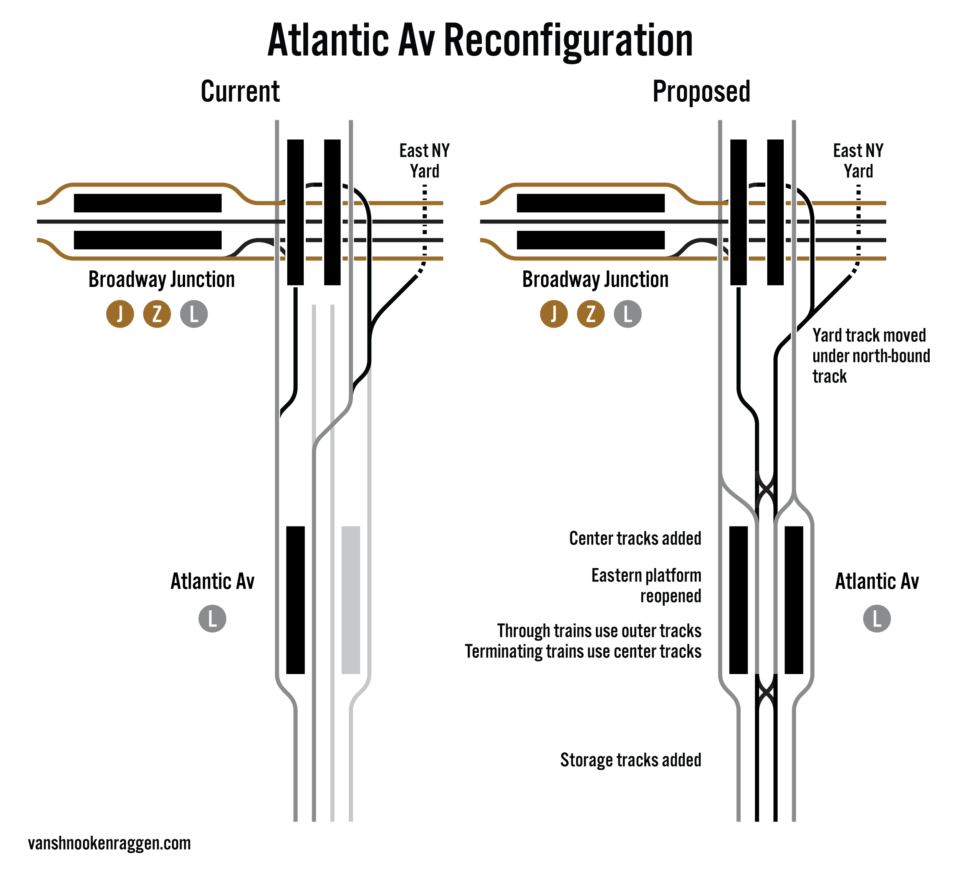

Atlantic Av station was once as much of an important transfer point as Broadway Junction is today. Here, a rider could take a train from Ozone Park and simply transfer across the platform to trains going to 14th St, downtown Brooklyn, or the Lower East Side. Today, the station has one platform in use, an entire platform abandoned, and the abandoned remains of a third, partially removed platform. Until the late 1990s, the L train actually served the two large platforms, but to save on maintenance costs, the tracks were realigned so that both Canarsie-bound and Manhattan-bound trains served a single platform. South of the station, you will see the remains of two abandoned trackways next to the active ones.

If Atlantic Av was to be expanded back to something closer to its original form, and the southern trackways reestablished and extended for 600′ trains, then the station could be used for a new short-turn terminal. Through-trains would use the outer tracks, while terminating trains would use the inner tracks. The layup tracks south of the station could hold four, 600′ trains, while two more could be held in the station. The track connection between the station and the East New York Yard would need to be rebuilt to prevent yard-bound traffic from passing in front of in-service trains.

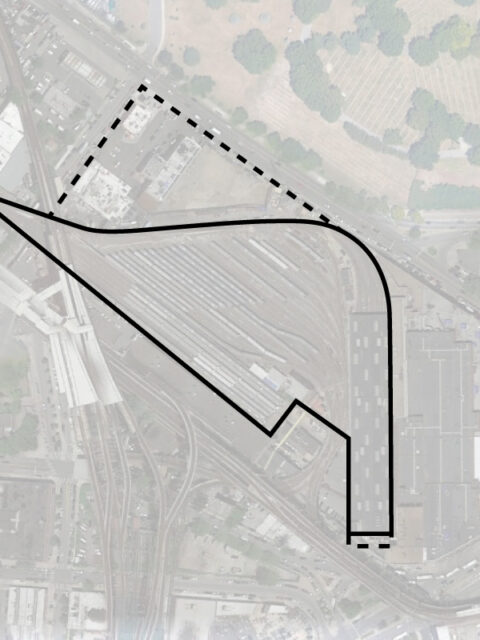

600′ trains would not be able to be stored in the East New York Yard until the next phase. But since L trains must access the yard to use the maintenance shop, the current shop would need to be expanded. This *should* be possible within the existing envelope of the site. But without blueprints of the building, I cannot know for certain. It may require an expansion of the property, which is something covered in the next phase. Should this not be possible, an alternative would be to upgrade the Linden Shops, a non-powered facility used by work trains, located on Linden Blvd and Rockaway Pkwy. Movements to this facility would foul up revenue service trains, so this is not ideal.

With these changes, the Canarsie Line should be able to see a bump in peak service from 24 TPH to 30 TPH, possibly more. With this total investment, 10-car trains and better terminal operations, rider capacity will rise from its present 93,312 PPH to 146,160 PPH in both directions at peak times, an increase of 56%. To put that into context, the first phase of the 2nd Ave Subway cost $4.5 billion and sees only 53,592 PPH in both directions at peak times (though, as designed, the line can handle twice that much, the MTA only runs the Q train at 11 TPH). These proposed changes to the Canarsie Line would buy as much of a capacity increase as the current 2nd Ave Subway, for less capital cost, and help far more people.

Phase 3

10-car Jamaica Line Platforms, East New York Yard Expansion

With all Canarsie and Myrtle Line platforms extended for 600′ trains, the final phase would be to extend the remaining Jamaica Line platforms. As mentioned above, this will require expanding the East New York Yard. The yard is hemmed in by development on the northwest side, and the massive East New York bus depot on the east. In order for the yard to be expanded, the private property on the northwest side must be acquired. As of this writing, these are all commercial properties.

The reasoning behind not extending Jamaica Line stations until the end is that there is a strong imbalance in ridership between stations west of Broadway Junction and east of the station. As covered in Phase 1, providing the J/Z with 30% more service should be more than enough to cover ridership growth for the foreseeable future. Phase 3 would only need to be implemented should ridership require the additional 25% capacity increase that 600′ trains would bring.

All remaining stations in Brooklyn and Queens are above ground and would be relatively cheap to expand. Broadway Junction would be the only station that would need extra work, given that the tracks would need to be adjusted. The two Archer Ave Line stations, Sutphin Blvd and Parsons Blvd, were built with longer platforms, so no work would need to be done underground.

The same can not be said for Manhattan. The remaining J/Z stations in Lower Manhattan would need to be extended, and it is these stations which will prove to be the most complicated and expensive to extend. Bowery stations should be straightforward, but the active side of the Canal St station is built below private property, leaving very little room to work with. The back-of-house facilities located at either end of the platform would need to be relocated, and this will still just barely cover it.

Chambers St station can only be extended northwards, meaning that the complex interlocking north of the station would need to be moved. This will require reengineering the tunnel to support the moved tracks. The tail track south of Chambers St, used for short turning trains, may need to be removed from service if extending it is not feasible.

Fulton St station is a bi-level station, where the southbound-platform is above the northbound. Here the southbound tracks rise up, before coming down to meet the northbound tracks south of the station. It should be possible to extend both platforms, but the grade at either end may be steep, possibly too steep for ADA compliance.

The Broad St terminal will be tricky as well. It appears that the platforms can be extended by using existing back-of-house facilities and existing passages (which currently act as egress points to the street and neighboring buildings). But the real challenge will be the layup tracks south of the station. Immediately south of the platform, the two tracks split into four, with the middle two tracks being used for storage and turning trains, while the outer two continue on to join the Montague Tunnel into Brooklyn. Passenger service on these connecting tracks ended in 2010 when the M was rerouted from Bay Parkway to Forest Hills.

Much depends on just how long these layup tracks are. There is a double switch which would, at the very least, need to be moved. It might be possible to move the switch to the southern edge of the platforms, but it also might need to be moved north of the station. It’s possible that the layup track tunnel would need to be extended south, though this might be a last resort option. If a feasible solution is not found, J trains may need to be extended back into Brooklyn through the Montague Tunnel, interlining with the R train.

Extending the remaining Jamaica Line platforms would run between $1.5 and $2 billion, not including yard expansion. There is more ambiguity on what would need to be done for the Manhattan stations. The yard expansion cost would depend on the real estate acquisition costs. Given the ridership on these stations, it may be a worthwhile investment, though one that could wait.

Jamaica Express

The final element of this plan is providing a true Jamaica Line express service from Manhattan to Jamaica. Given the limited number of additional trips that can be made over the Williamsburg Bridge, it is questionable if such a service is possible. Much like the F train as it runs through Brooklyn, there is higher ridership as one gets closer to Manhattan, meaning that any express service will help fewer riders at the end of the line while reducing service for more riders closer to the beginning. The major difference between the F and the J here is that the J is possibly the only train that can reduce crowding on the Queens Blvd express.

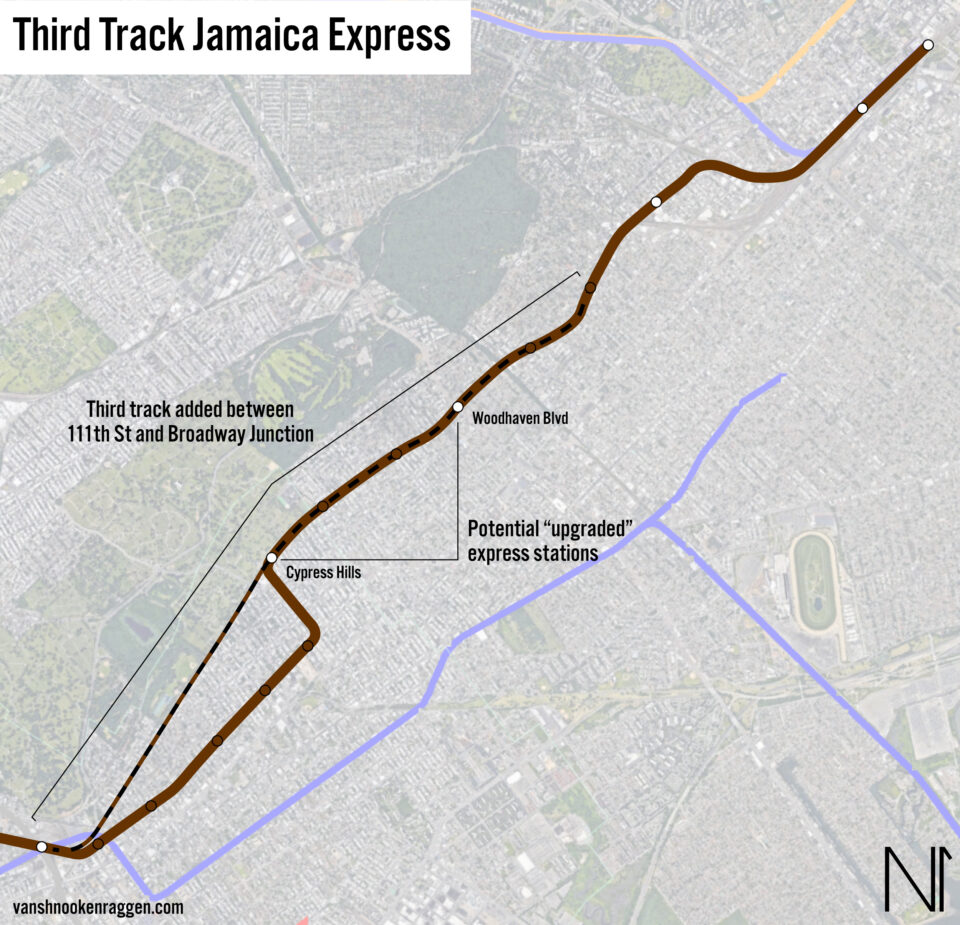

The early designs of the Broadway-Brooklyn El, before it was extended to Jamaica, were two tracks with island platforms in the center. The track section between Alabama Ave and Crescent St stations still features this design. A middle track was only constructed in key locations where storage was needed. But this space allowed for a future extension of a full middle-express track during the Dual Contracts.

As part of the Dual Contacts, the island platforms were rebuilt to the sides of the track, while express stops were built with dual-islands. The express track was only built between Marcy Av and Broadway Junction, while the Jamaica Ave El structure between Crescent St and 168th St was built with side platforms and provisions for a middle-express track to be added later. To overcome the space constraints along the East NY-Cypress Hills section, the plan was to elevate the express track above the local tracks and stations (which was a feature of the older els in Manhattan).

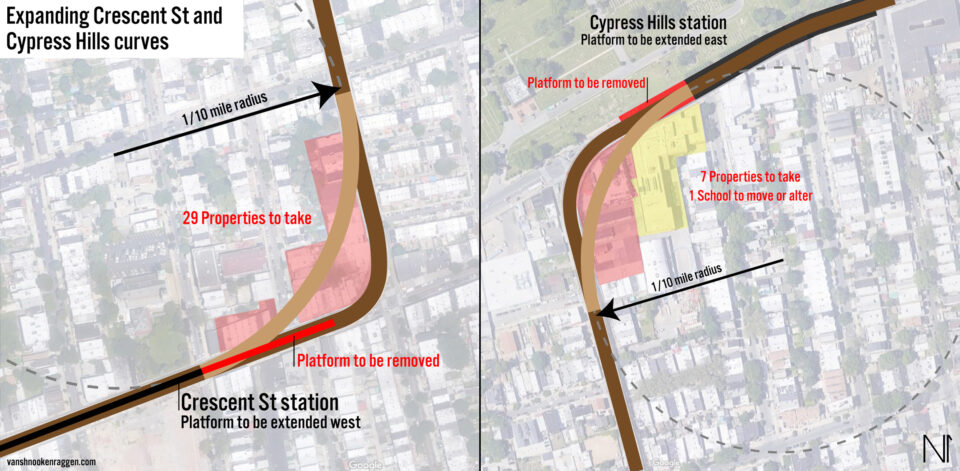

As mentioned before, the un-upgraded section between Alabama Av and Crescent St likely cannot handle the additional track. Additionally, the existing el track makes a famous S-curve along Crescent St, where the line moves from Fulton St to Jamaica Ave. These curves are some of the sharpest in the system and even if there were an express track running the length of the line, trains would have to slow down to make both curves, greatly reducing the time savings.

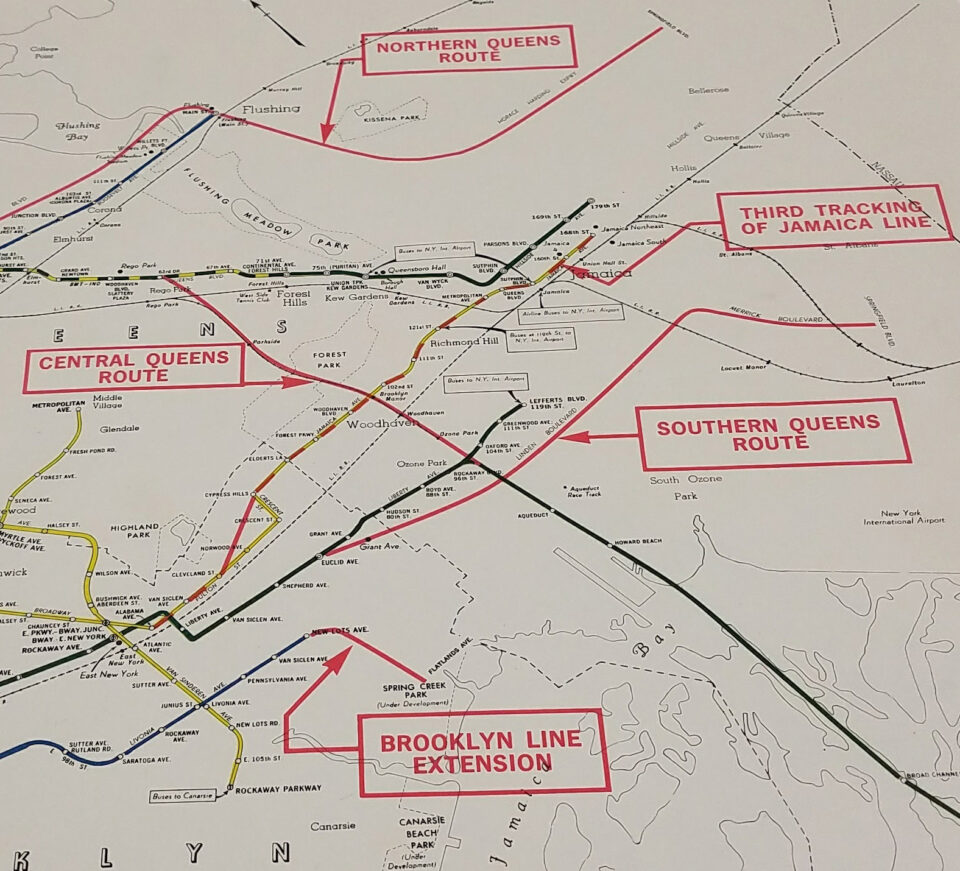

In the 1950s, NYC Transit Authority planners were looking at ways to reduce crowding on the Queens Blvd Line express trains. They reasoned that if the BMT Jamaica Line had an express track, then it could provide an attractive alternative for riders. They devised a scheme which built a third track from 168th St to Cypress Hills, at which point the express track would plow through some 70 homes along a diagonal route to the Cleveland St station, after which the track would run above the existing line as described before. Needless to say, this was rejected outright by the community.

Building an express track along a different route is probably still the only way that you could bridge the Cypress Hills section of the Jamaica Line. Even if the sharp curves along Crescent St were to be widened, using the same radius as that of the A train as it turns through East New York, it would require taking a number of buildings at either curve. There is also a school on Jamaica Ave which would be impacted. The Crescent St and Cypress Hills stations would need to be moved back. So building a single express track along Jamaica Ave, separate from the existing elevated tracks, may be the only way.

The track would begin at Broadway Junction, where the existing express track ends. It would rise over the local tracks, but instead of heading down Fulton St, it would turn down Jamaica Ave. Between Alabama Ave and Warwick St, the single track viaduct would run down the center of Jamaica Ave. After Warwick St, the structure would move to the sidewalk, along the southern edge of Highland Park. From here it would continue along Jamaica Ave until Euclid Ave, where it would move back to the center of the street and fly over the existing elevated tracks. The express track would descend to meet the existing structure east of Cypress Hills station, where it would continue along the existing structure until it meets with the middle layup track at 111th St.

Express service would run in peak directions at rush hour. Stations would be (east to west): Parsons Blvd, Sutphin Blvd, 121 St, Broadway Junction, Myrtle Av, Havemeyer St, Essex St, Bowery, Canal St, Chambers St, Fulton St, Broad St. “Upgraded” express stations in Woodhaven should be considered, possibly Woodhaven Blvd or even Cypress Hills. However, the value of this express service is its time competitiveness against the Queens Blvd express. Adding more time to the trip reduces its value.

Presently, the E train takes approximately 28 min to travel from Parsons Blvd to Lexington Av-53rd St. By assuming speeds of 40 MPH on the Jamaica express track, and adding in the current express service, a fully express J train could travel from Parsons Blvd to Essex St in approximately 25 min. The obvious difference is that the E train directly serves the Midtown central business district, while the express J would still require riders to transfer to the M or F train, and continue their journey. Additionally, the J express would be more time competitive to the Wall St area versus the express A train available at Broadway Junction.

Full Jamaica express is therefore a “nice to have” that should be left to a time when there is more demand. This is probably not as far off as one might imagine. Downtown Jamaica continues to grow in population, and the expansion of JFK Airport will no doubt fuel this growth. In a post-pandemic world, more people are moving away from the traditional 9-5 commute, meaning that there will be growth in non-traditional transit patterns. Only through investing in better outer borough transit can the system take advantage of this new reality.

Conclusion

Many of the ideas from this post were first developed in 2019 and 2020 as part of a deinterlining report that I was working on with Uday Schultz. The report was multifaceted, but the overall idea was to look at ways to increase capacity. The improvements to the Jamaica and Myrtle Lines focused less on pure deinterlining (given ridership trends, reverse branching the M and J are worth the delays) and more focused on fixing a very old piece of infrastructure.

Many of my old futureNYCSubway proposals included a new tunnel between Manhattan and Brooklyn in Williamsburg. The growth in population and in ridership justified it, I thought. However, when I realized that the Eastern Division is limited to 8-car trains, and that extending them to 10-cars would provide 25% additional capacity “overnight” (relative to the time it takes to build an entire new line), the benefits of fixing what we have over a new build were clear.

To clarify, adding two more cars seems like it would only add 20% capacity, but NYC subway trains are put together out of A type and B type cars. A types include a cabin for the operator, offering fewer seats. So an 8-car train would be set up A-B-B-A-A-B-B-A. A 10-car train would add two B types, which carry more riders. That’s where the extra 5% comes from.

Given current subway construction costs, it’s conceivable that a new-build subway under the East River would START at $10 billion. That assumes we know where it would go. Initially, this post was going to look at some options, but it was running long, and I didn’t want reads to get distracted from the fantasy. By spending half of what it would cost for a new line (probably far less than that), we can greatly improve service and capacity not only in Brooklyn, but also in Manhattan and Queens. This will likely provide more than enough room for growth for another generation or two.

I wouldn’t propose any kind of timeline for a project like this. Post-pandemic ridership is still 1/3rd lower than it was in 2019, so there is room for growth. These recommendations are more about starting the conversation about how we can use what we have more effectively. I’d also note that the site plans I’ve drawn up are rudimentary at best, and are not egineering documents. Many of these ideas might not be possible, but they should be considered. If these plans are worked out now, we can be more ready for them when the time comes.

Excellent article! the Williamsburg Bridge Transit plaza rendering is an exquisite find. Many thanks!

Phase 1 should be canarsie line capacity improvements, since it’s the most capacity strained part of the eastern division. Essex St might get packed during rush hour waiting for a delayed J train, but the J delays don’t come from overcrowding. As you pointed out, the canarsie line currently has issues with overcrowding in Manhattan which affects timely service. Union square gets dangerously crowded even with the L operating normally, and then goes to first av and has take all the passengers from this pretty busy station on trains that are already packed. The only part of phase 1 which might have an impact on current overcrowding is a new union av transfer to the G, which might reduce the transfers at met Lorimer. I don’t really ride the QB line often, but my understanding of the situation is that it’s specifically the express trains that are overcrowded and that the M ran light into Manhattan before the 63rd street closure. The M in Brooklyn is nowhere near capacity, and the trip between Myrtle – wycoff and 14 st – 6 av is a lot shorter and a lot more crowded on the L. Also, the crowding on the L extends, albeit to lesser extent, for more hours that on many other crowded lines, which suggests to me a lot of unmet demand.

Spot on! In my opinion, the addition of layup tracks west of 8th Ave is the most important part, followed by the change to Union Ave-Broadway.

What about the prospects of rebuilding the Canarsie line’s at-grade sections as elevated and extending to Seaview Av to better serve Canarsie? I thought about this, but I’m not sure if it is practical or pure fantasy. As for the Jamaica line, I am in favor of the infinite-money-glitch approach and just burying the entire line as a subway.

There’s no point in extending the L any further into Canarsie. Even if building another el line was politically palpable (which it probably isn’t), the ridership isn’t worth it. Buses serve the last mile (literally) better than one more stop on the L. It’s not like the area has land to develop that would make such an extension worth while.

These are definitely some really interesting ideas. I thought that the reason for the M to go up 6th Avenue was simply to cut down on one line to save money. Instead of having the M and the V, you only have the M. However, the cost of that was that the V could have 10 car trains while the M could only have 8. As a result, the passenger capacity on the Queens line was reduced. If the V were brought back, that passenger capacity on the Queens line could be restored. On the other hand, there are many riders today who like being able to take the M through the Chystie St. connection up 6th Avenue. If the V were brought back, then would come the question of what to do with the M. It could go back during rush hours to Bay Parkway, but as I understand it, there is really no need for that. In an unrelated direction, the idea that has been presented on this site previously that looked the most useful to me was the Northern Blvd. line, even independent of anything involving the 2nd Avenue subway. Not only, as it is shown, would it go to Main St. Flushing, easing the load on the Flushing line, but it would also go to places like College Point eventually. And it could be connected to the 63rd Street tunnel, which is underused now because there is insufficient capacity on the Queens Blvd. line for additional trains coming from there. Back to these suggestions, though, I like most of them. I think the big two for me are the improvements to the L, particularly establishing tracks beyond 8th Ave. for terminal use and the Havemeyer St. station!

I could see a benefit of having a station on flatlands rather than just Glenwood. Maybe in between the two. The situation now makes all the flatlands ave buses have a pretty difficult detour to reach the station