The New York City subway is famously made up of three formerly private railroads; three distinct networks that were planned to be separate and, at best, to compliment one another. Looking at the subway map today, it’s hard to see the layers of history when then overall composition looks like a mess of spaghetti dropped over a map of the city. But each line has a story to tell, and each story relates to another.

Elevated trains are synonymous with New York City (and Chicago for that matter). A complex web of elevated tracks once covered much of Manhattan and Brooklyn. But with the advent of the subway, the city pushed to remove the els from its streets. Some els were built as part of the subway, and these were planned to stay. But the older els were not long for this world. Today, only a small section of pre-subway elevated tracks remain along Broadway and Myrtle Ave in Brooklyn. Like the Coelacanth, they somehow survived despite the odds.

The First Elevateds

The subway that we know today was not the first transit network the city had. Horse-drawn carriages, first with wooden wheels but soon with metal wheels running on iron tracks embedded into the streets, were the original mass transit. Private omnibus companies created chaos on the streets, with traffic jams so bad that, at one point, the city considered building pedestrian bridges over Broadway so that people could cross.

As the city grew northward, the increasingly long omnibus rides became untenable. While London had opened the world’s first subway line in 1863, it was a notoriously dirty and dangerous affair, as steam locomotives would quickly fill the tunnels with smoke and soot. Ventilation was primitive and non-effective, and it would be a generation before electricity could even be produced, let along used for train power.

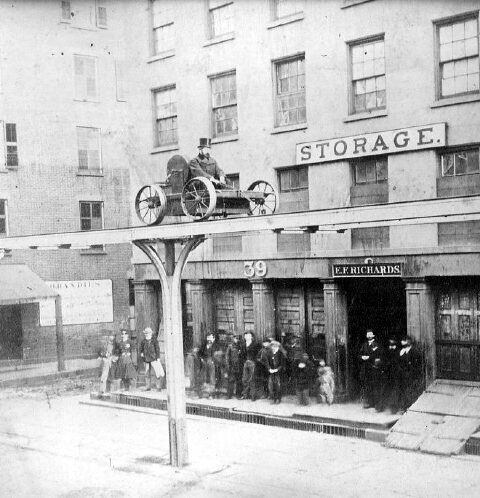

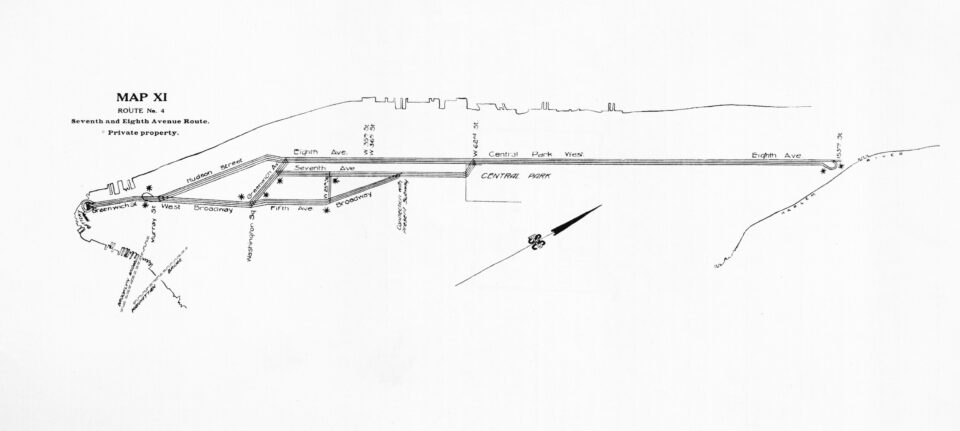

The only alternative, like so many things in New York, was to go up into the sky. The first elevated rail line, soon simply known as an “El”, opened in 1868 as little more than a technology demonstration. The single track was lifted above the sidewalk along Greenwich St and 9th Ave, between Battery Place and 29th St. The track was supported by a line of single columns made of steel beams, giving it the nickname of the “one-legged railroad”. The line used cable cars pulled by a mile long cable running along the tracks. Deemed a success, the West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway Co was given a license to extend its railroad all the way to Yonkers.

Despite this success, the railroad soon ran into legal and technological troubles. The cable car technology was inconsistent, and the mile long cables often snapped. The railroad was allowed to convert the line to steam power, and strengthened the supports. Ridership was low (due in part to the small number of original stations) and the railroad defaulted on three mortgages. In 1871 the railroad were sold at auction and reorganized as the New York Elevated Railroad (NYER).

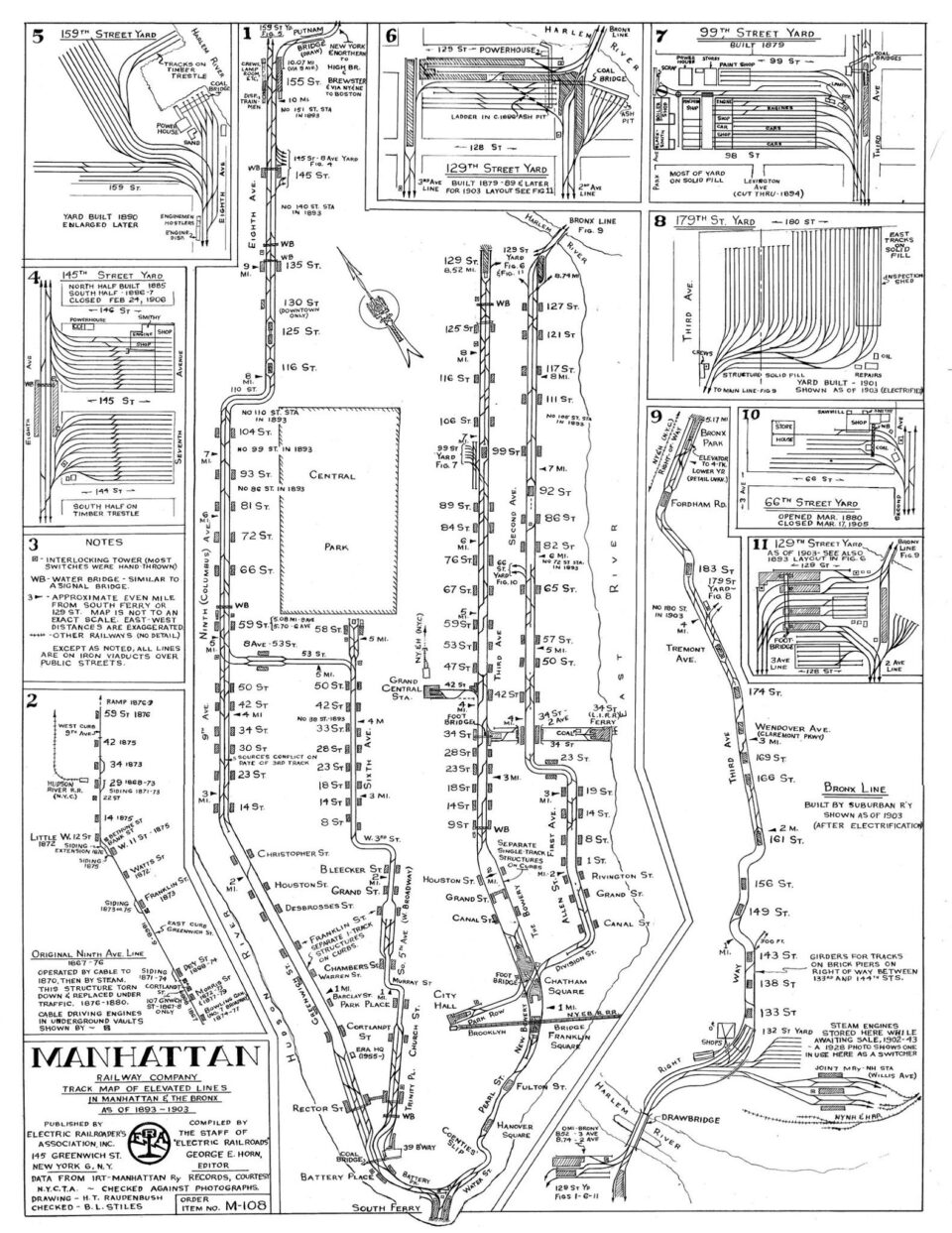

The NYER set about expanding the line. It added new stations and began extending the track northward. In 1878, the railroad began to double-track the line. By 1879, the line had been extended all the way to 155th St. The success of the NYER lead to a scramble to build other lines. In 1878, els along 6th Ave, 3rd Ave and 2nd Ave began growing skyward and northward from the tip of Lower Manhattan to Bronx Park in the Bronx.

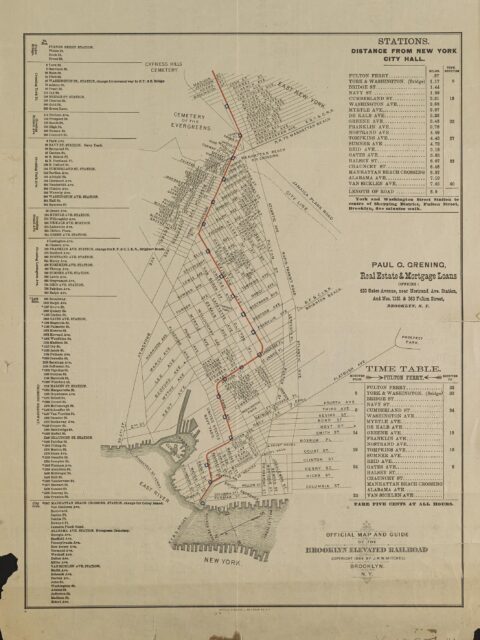

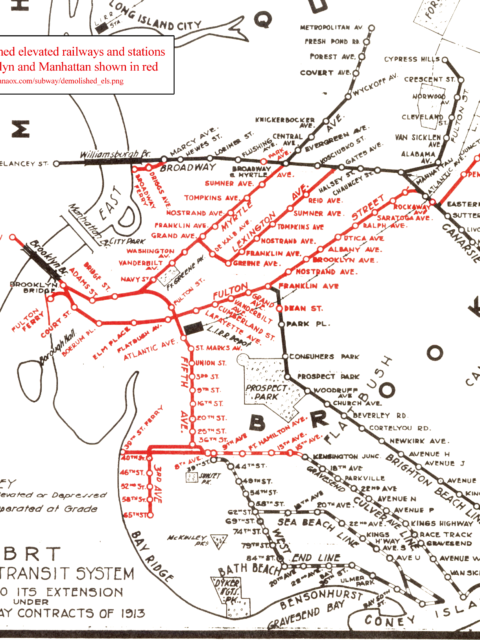

In 1883 the Brooklyn Bridge opened and the once sleepy suburb of Brooklyn began to grow into a city in its own right. Taking advantage of the new bridge, the Brooklyn Elevated Railroad opened in 1885, zigzagging from the base of the Brooklyn Bridge, along Myrtle Ave and Grand Ave through Fort Greene and Lexington Ave through Bedford-Stuyvesant (before it was called that), terminating at Broadway and the border of Bushwick. Three years later, the Union Elevated Railroad (UER) built a line along Broadway between Williamsburg and Cypress Hills. The UER also extended a line down Myrtle Ave, connecting all three elevated railroads.

In 1888, two additional elevated railroads opened to other parts of Brooklyn. The Kings Co. Elevated Railroad was extended along Fulton St between Fulton Ferry and today’s Broadway Junction, and the 5th Ave Elevated Railroad was extended south along 5th Ave, spurring development in Park Slope, Sunset Park, and Bay Ridge. These elevated lines connected with existing ground level steam railroads that brought riders to Coney Island.

Originally, all railroads were powered by steam trains. In the mid 1880s, inventor Frank Sprague developed a way for streetcars to be powered by overhead electric wires. The first functional electric streetcar line opened in Richmond, VA in 1887. By 1890, the streetcar network in Boston, MA had converted many of its horse-drawn lines to electricity. By 1903, the New York City streetcars and elevated lines had switched over.

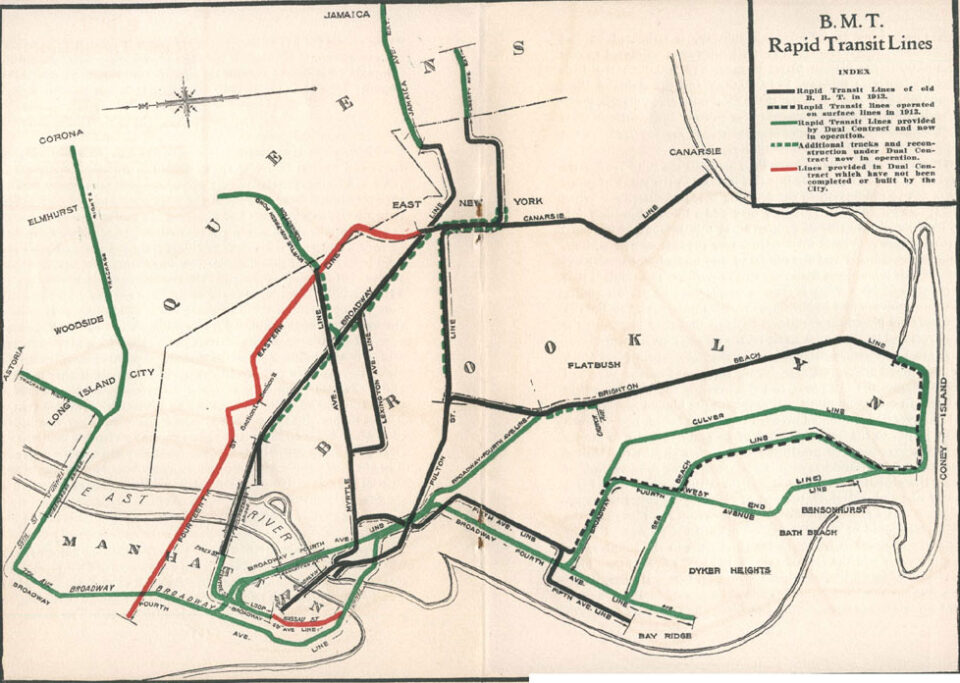

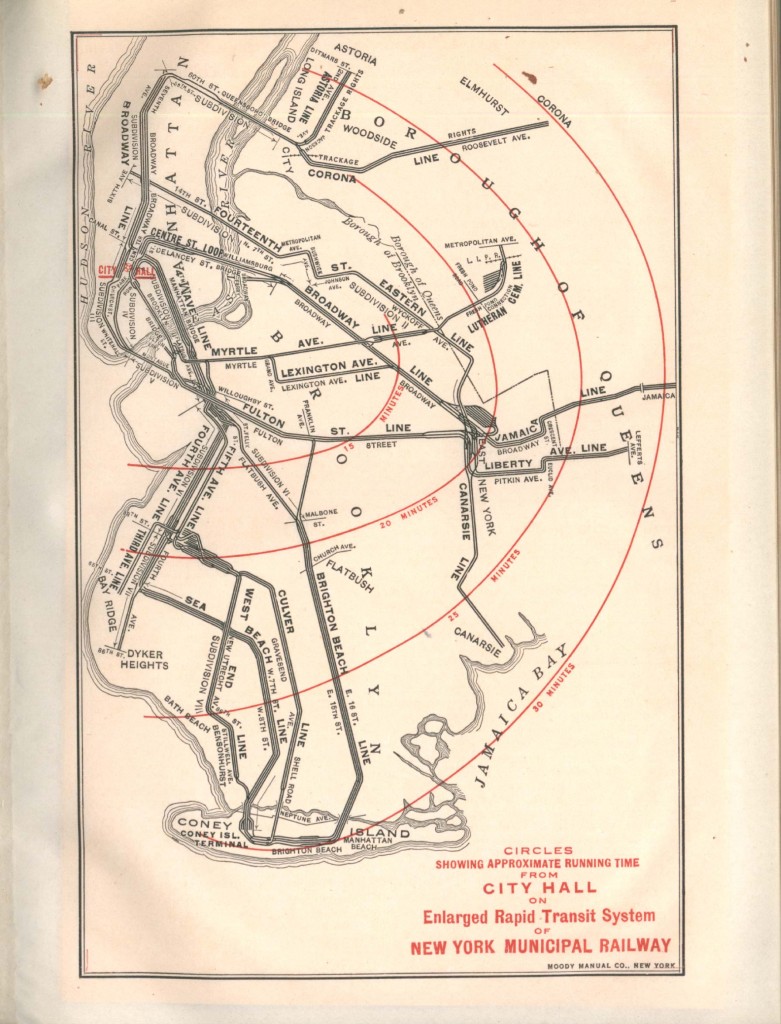

By the turn of the 20th Century, 40 years of growth had created the first modern mass transit system in the United States. In Manhattan and the Bronx, control over the elevated lines had consolidated into the Manhattan Railway Co. In Brooklyn, the complex network of streetcars, elevated lines, and steam trains headed to Coney Island had been consolidated into the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. (BRT).

Elevated Subways

Elevated lines can be broken into two types: pre-subway and post-subway. In 1897, the first electric subway operation in the United States started in Boston. New York saw this as the logical next step and contracted the newly formed Interborough Rapid Transit Co. (IRT) to build and run the first subway.

Pre-subway elevated lines were glorified streetcars in the sky. The cars themselves were made of wood and were relatively light-weight. Elevated cars were longer than streetcars and often had adjustable entrances to allow for low-level boarding or high-level boarding. After conversion to electricity, these trains could run using either third rail power or overhead trolley wire. The low-level cars ran a hybrid elevated-streetcar operation.

For instance, el trains ran between the Broadway Ferry at the East River in Williamsburg to 168th St in Jamaica. Trains ran elevated until Cypress Hills, then used a ramp to reach streetcar tracks on Jamaica Ave. This operation was stopped after a few years due to street congestion delaying trains. Similar operations were run using the 5th Ave El and many of the ground-level steam train lines to Coney Island.

Post-subway elevated lines were designed to carry the larger, heaver trains that would be used in the new subway. In Inwood and the Bronx, which were less developed, the IRT built their subway lines as els. Pre-subway els often used 2 or 4 car train sets. The subways would use 5-car sets for local service and 8-car sets for express trains. The new subway trains also had faster, but heavier, engines.

As part of the next phase of subway building, known as the Dual Contracts, both the IRT and the BRT were given allotted new subway lines to build and operate. The IRT had taken over operations from the Manhattan Elevated Railway Co, and began connecting their elevated lines with new lines in the Bronx. The 9th Ave El was extended over the Harlem River and connected with the new IRT Jerome Ave Line while the 3rd Ave El was connected to the IRT White Plains Rd Line at two places: at 149th St and at Gun Hill Rd.

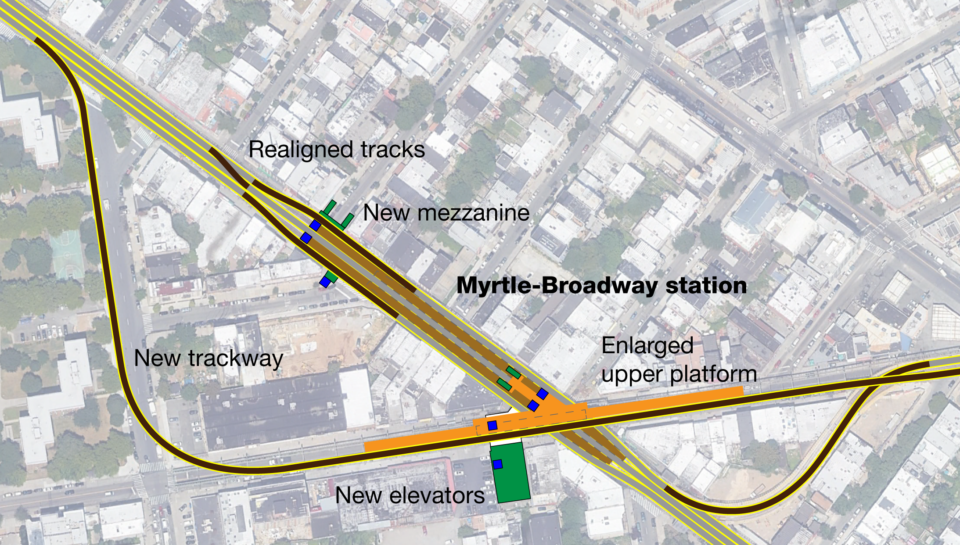

The BRT was given the right to upgrade older elevated lines and convert the old steam lines to Coney Island into new elevated lines. The BRT added third tracks to the Fulton St El and Broadway El. They added a third track to the Myrtle Ave Line between Broadway and Wyckoff Ave, and extended the elevated tracks along a steam-dummy through Ridgewood to Metropolitan Ave. It converted the West End and Culver Lines to els, and built trenches for the Sea Beach and Brighton Beach Lines, all of which were then connected to the BRT’s new trunk subway along 4th Ave and over the Manhattan Bridge.

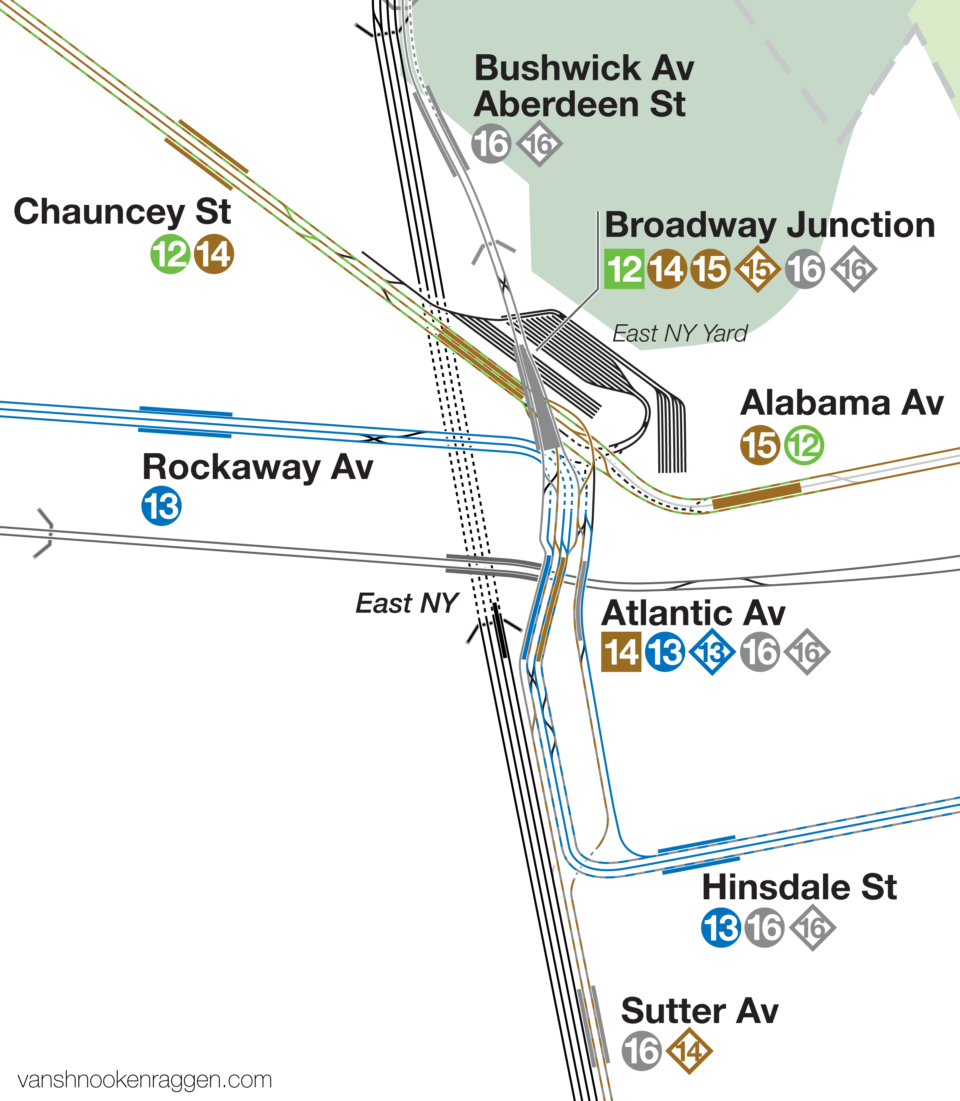

The BRT also built out a new subway for northern Brooklyn, the 14th St-Eastern Line (today’s L train). This subway would connect to the existing elevated network at Broadway Junction. Previously, the Canarsie Line had been a steam railroad branch off of the LIRR, running to the edge of Jamaica Bay where riders could change to steamboats to the Rockaways. The BRT had electrified the line in 1906 and connected it to the Broadway and Fulton St Lines. In 1924 the BRT connected the 14th St-Eastern Line directly to the Canarsie Line. While doing this, they greatly expanded the Atlantic Ave station in East New York. Riders from the Fulton St Line, Broadway Line, and now 14th St Line could make cross-platform transfers, or trains could reverse branch along other lines.

Both companies made it a point to differentiate lines which were elevated and which were subways. The lighter el trains could run on the new subway-el structures, but the heavier subway trains could not run on the older elevated tracks. In Brooklyn, the Fulton St El and Broadway El were upgraded with stronger support beams and third tracks for express service. The Broadway El had been connected to the new Centre St Subway, and the Fulton St El was planned to connect to the 4th Ave Subway at DeKalb Ave, but this connection was eventually dropped due to a lack of capacity.

The End of Els

El trains were never popular with the city. The large structures dominated the street, casting them in shadow at all times of day. The early trains would spew soot and smoke directly into people’s windows. The noise was infamous.

Much of the noise comes from the structures themselves, which act as amplifiers. Heavy concrete or earth track structures absorb and deaden noise. The steel beams shake with the vibration of the train, making them louder.

But for 40 years they were a necessary evil. When it proved feasible to put trains underground, city leaders immediate began dreaming of a world where the els were gone. But for the companies which built and operated the subways, the els were moneymakers, and they had no plans to remove them.

The els were so hated that in the more built-up sections of the city their expansion was outright blocked. The BRT had intended on building their 14th St-Eastern Line as a subway through Williamsburg and then elevated through Bushwick along the LIRR Evergreen Branch, a narrow gauge railroad running through city blocks between Wyckoff and Irving Aves. The neighborhood fought the BRT until they agreed to run the line underground along Wyckoff Ave. The original Crosstown Line, running from Long Island City, through Greenpoint, Williamsburg and Bedford-Stuyvesant to Crown Heights, was fought to a standstill by local communities.

Early subway lines complemented the elevated system. Now, with subways proving their worth, new lines were planned that would replace the els.

In 1918, John Hylan was elected Mayor of New York. The Hylan mythology is that he was fired as a motorman from the BRT after missing a stop while driving an el train. Supposedly, he vowed to seek revenge on the private subway companies. Once Mayor, he paused all subway expansion and sought to create a municipal subway company that would drive the private companies out of business.

While this makes for a great story, the truth of the matter is more complex. Many, many people hated the private companies at the time. Service was bad, trains were crowded and dirty, and many areas of the city had no service as the companies didn’t deem expansion a worthy investment. The BRT had, in fact, already begun to face hard times after the Malbone St wreck killed 93 people, and declared bankruptcy in 1918. It restructured as the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Co. (BMT) in 1923. The city, for its part, wanted to rid itself of the hated el trains as they saw them as an impediment to growth and higher property values.

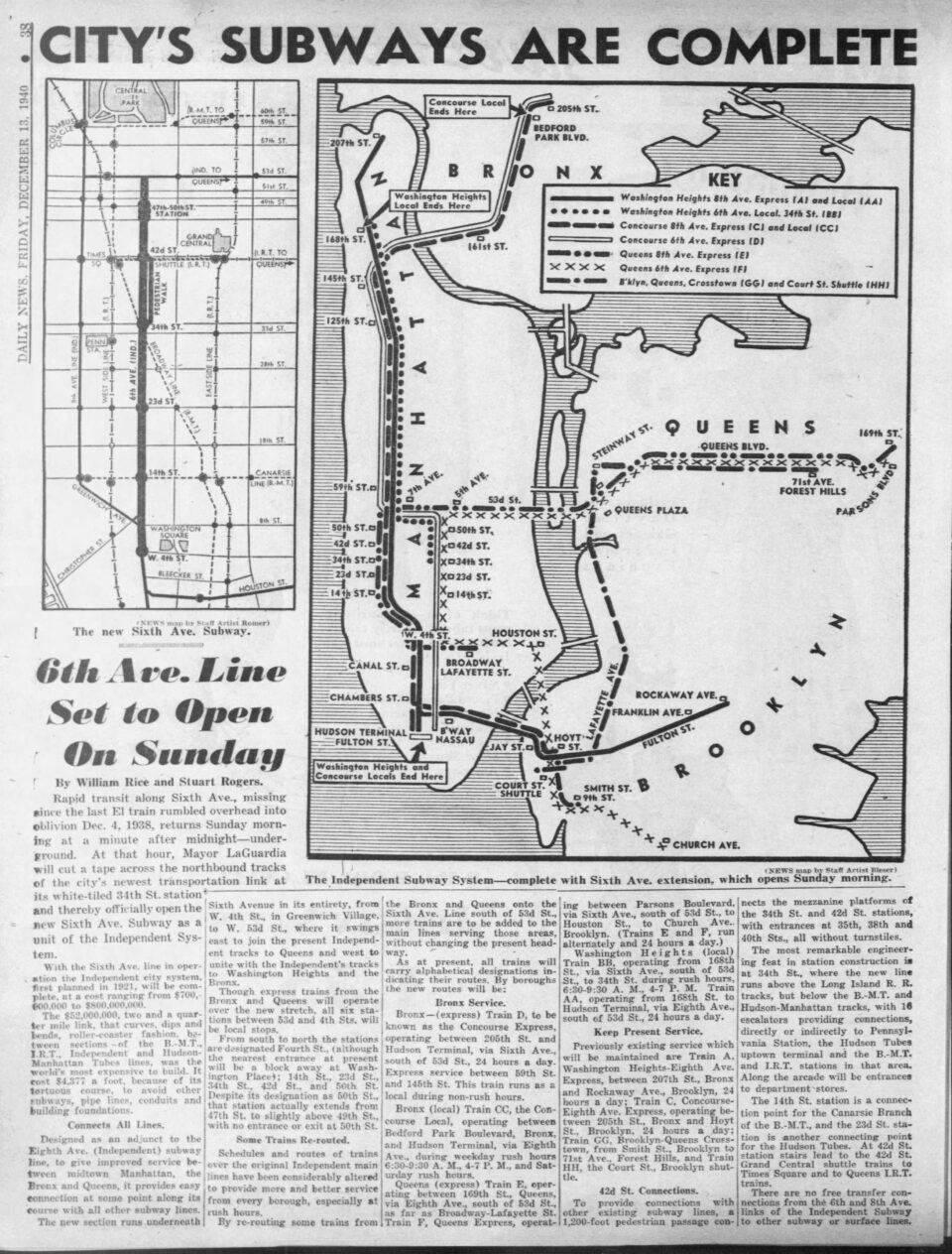

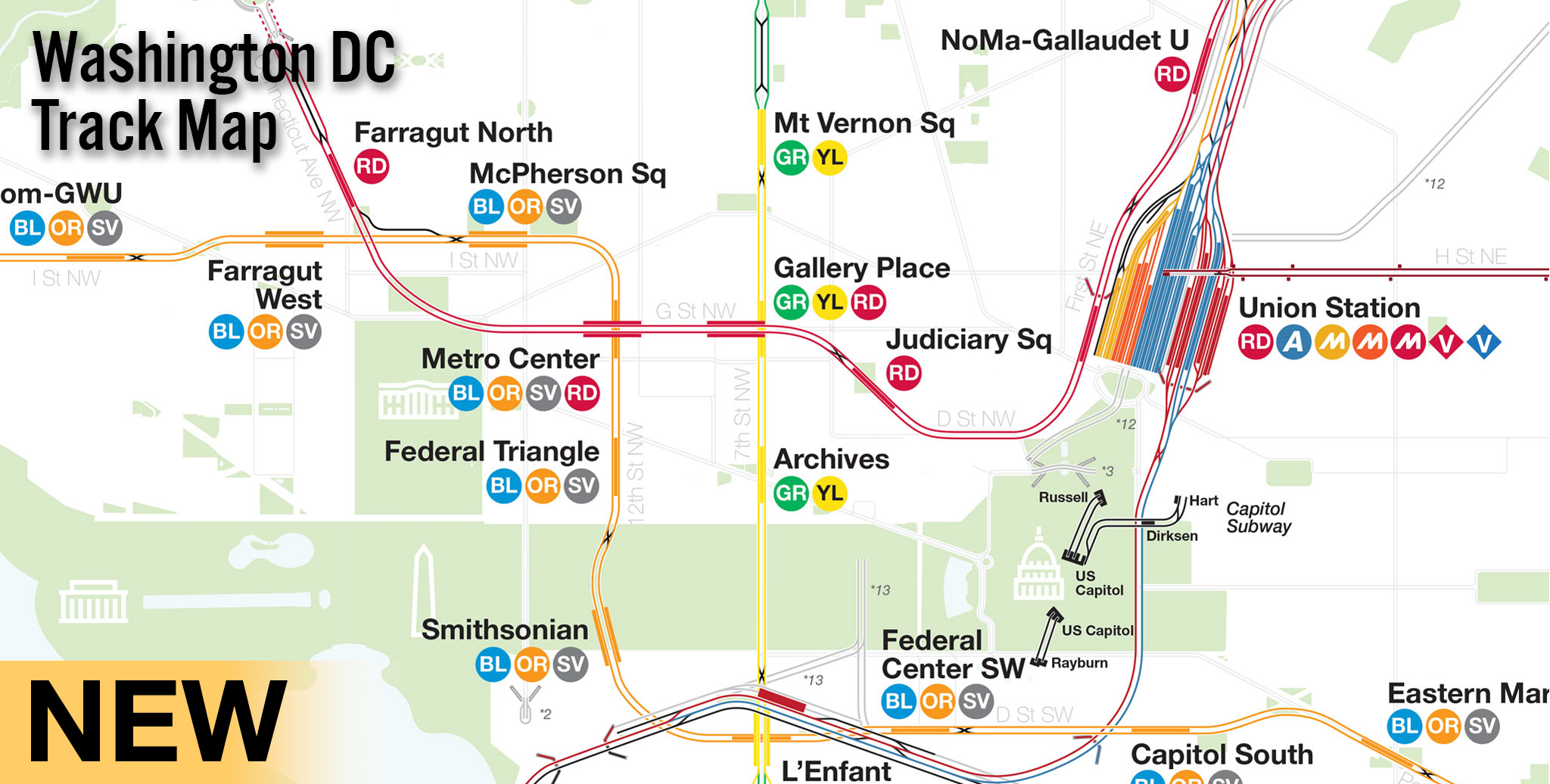

Hylan created his own subway company, the Independent City-Owned Subway (IND), which was specifically designed to replace existing elevated lines. In Manhattan, the ancient 9th Ave and 6th Ave Els were to be replaced by the IND 8th Ave and 6th Ave Lines. The 9th Ave El had been extended into the Bronx when the IRT built their Jerome Ave Line, on which it ran reverse branch service. Since the IND couldn’t run trains on the IRT, they opted to simply build a parallel subway under the Grand Concourse.

In northern Brooklyn, the Fulton St El was to be completely replaced with a subway. The route of this line evolved quite a bit. The IND originally envisioned a subway as far as Broadway Junction, but kept open the idea of connecting the Jamaica Ave and Liberty Ave Els at the eastern end of the line. Eventually, it was decided to simply replace the entire Fulton St El, creating a trunk line for southeastern Queens. The Myrtle and Lexington Ave Els were to be replaced with the new IND Crosstown Line subway.

The IND South Brooklyn Line (today the F and G trains) was developed to finally replace the 5th Ave El. This elevated line had been kept around after the opening of the parallel BMT 4th Ave Subway since the capacity constraints at DeKalb Ave were so great that additional el service was needed for the numerous branches in southern Brooklyn. By relocating service on the BMT Culver Line, the IND could open up space for additional trains on the BMT Sea Beach (N), Bay Ridge (R), and West End (D) Lines, allowing for the demolition of the 5th Ave El.

These lines, known posthumously as IND First System, eventually succeeded in replacing their respective elevated lines. The subways offered more speed and service, and were virtually invisible underground. The only sections of elevated tracks on these lines which remains today are the newer, post-subway expansion along Liberty Ave in Ozone Park, Queens, and along McDonald Ave in southern Brooklyn (along with the Gowanus Viaduct, the only section of the IND that was built as an elevated structure).

Even after this massive project, there were still a number of elevated lines still standing. On the east side of Manhattan, the 3rd and 2nd Ave Els had remained due to their reach into the Bronx. In Brooklyn, the Broadway and remaining Myrtle Ave Els had survived because they fed directly into the subway at Delancey St. The IND set their sights on these lines with their ambitious Second System plan.

An El Too Far

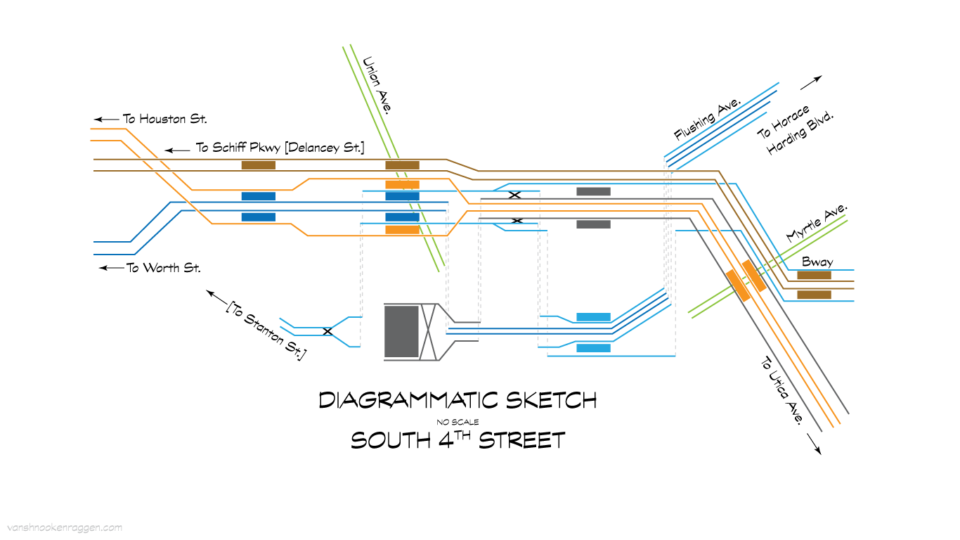

The Second System was designed around two core trunk lines: The 2nd Ave Line and the South 4th Line. From there, new branches into the outer boroughs would feed riders into Manhattan.

The city took the long view that removing the old els would be in the best interest of the city. The IND set about building on their initial plans for a second phase of work. They proposed a 2nd Ave Subway to replace the 3rd Ave and 2nd Ave Els from Lower Manhattan into the Bronx. This was also to reduce crowding on the IRT Lexington Ave Lines, who’s branches fanned out across almost all parts of the borough.

The IND South 4th Line was specifically aimed at replacing the oldest sections of the Broadway and Myrtle Ave Els, while also finally completing the Utica Ave Line, a branch through southeastern Brooklyn which, like the original Crosstown Line, had been proposed as an el but opposed by residents. This would be the core trunk of a network of new branches that would stretch across northern and southeastern Brooklyn, and into Queens.

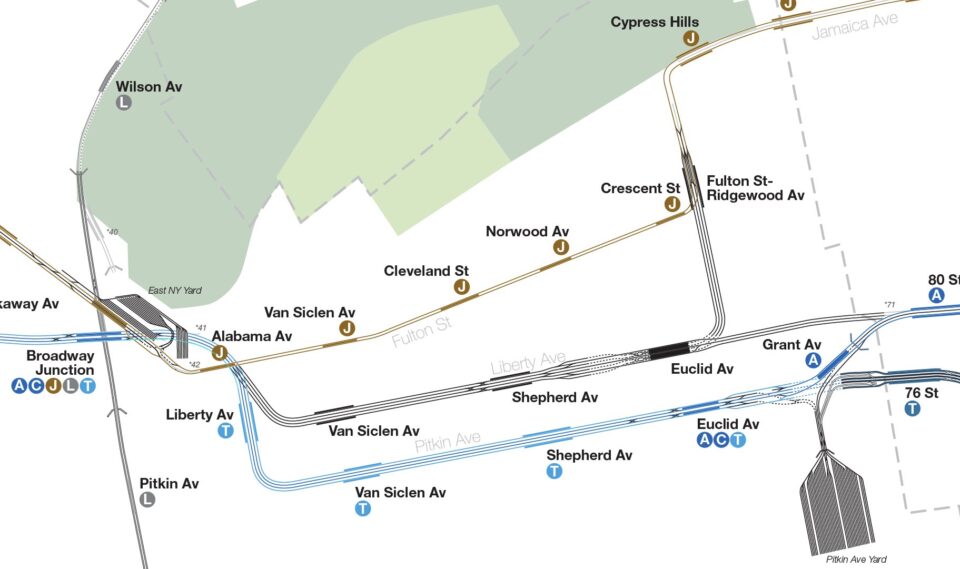

The IND Second System aimed to finally remove all pre-subway elevated lines. Unfortunately, as we know, that didn’t happen. With the “completion” of the first IND system, the city set about closing and removing the 9th Ave, 6th Ave, and 5th Ave (Brooklyn) Els. The Fulton St El was partially demolished from downtown Brooklyn to Rockaway Ave in 1940, but the remaining section along Pitkin and Liberty Aves was left running until the city was able to finish the IND Fulton St Line extension to Euclid Ave in 1948.

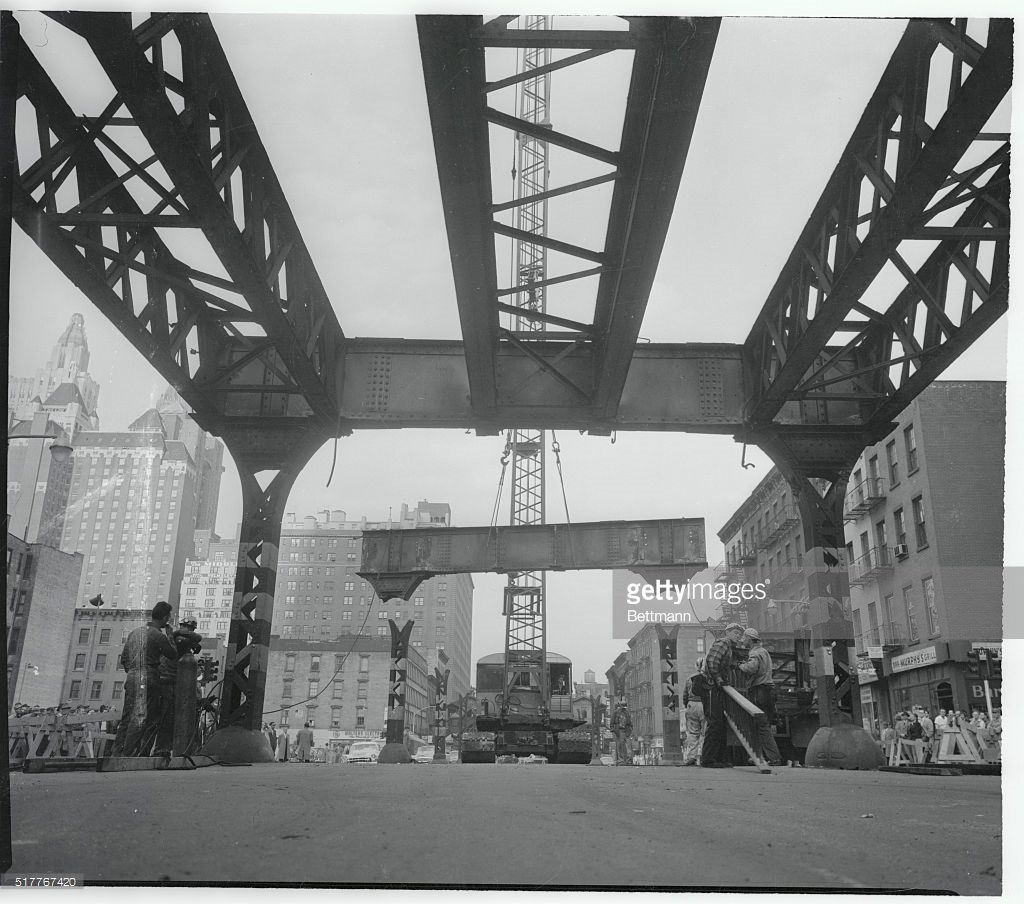

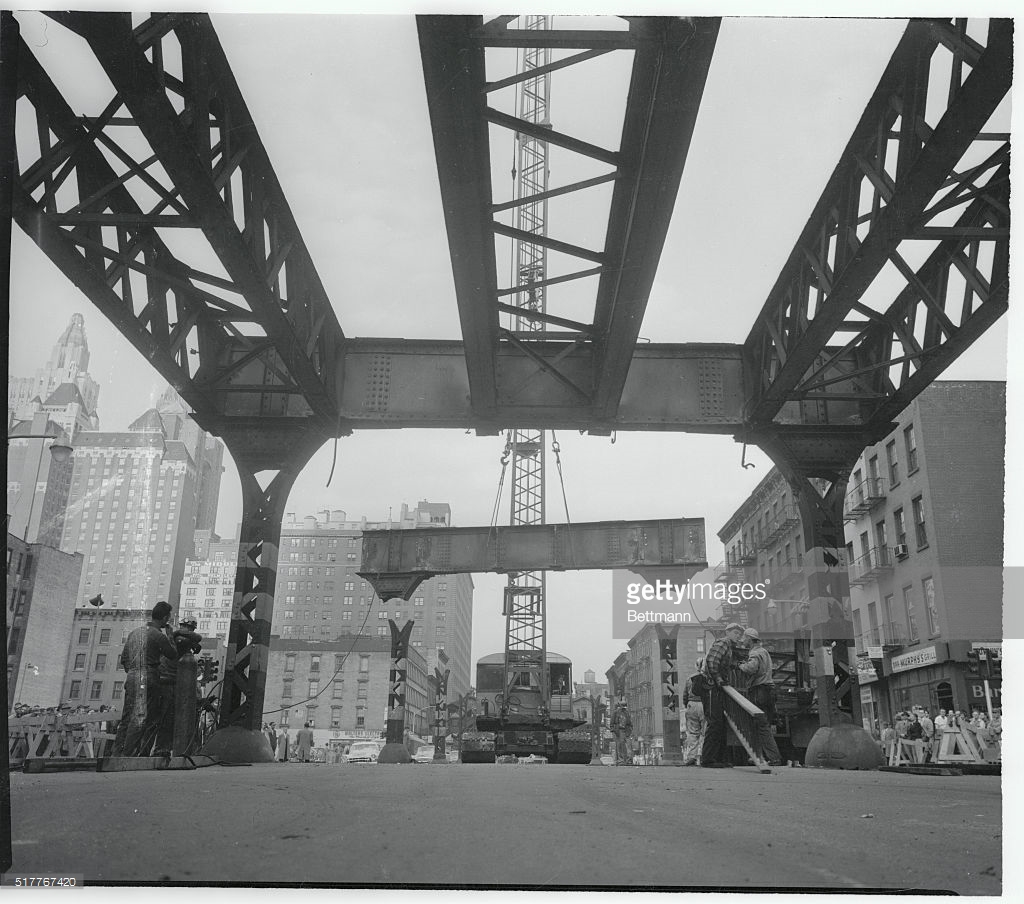

The plans for the IND 2nd Ave Subway led the city to remove the 2nd Ave El by 1942 even though there was no money for building subways. After World War 2, subway ridership saw the beginning of a long decline in ridership. The Lexington Ave El in Brooklyn was closed in 1950. That year, a $500 million ($6.3 billion in 2023) bond act was passed with the promise that work on the 2nd Ave Subway would begin. But the city acted too quickly and in 1955 began to pull down the 3rd Ave El, from City Hall to 149th St in the Bronx. It was then revealed that the costs of the subway were far higher than predicted, and the money was spent to shore up the existing system.

A few of the old els hung on a little longer. The Myrtle Ave El, from Jay St in downtown Brooklyn to Broadway, finally met its demise in 1969. The section of the 3rd Ave El in the Bronx held on until 1973, when it was finally demolished. The short Culver Shuttle, which had been the original connection between the BMT Culver Line and the BMT 4th Ave Line until it was cut off by the IND, was killed off in 1975. The very last el structure to be torn down was the end of the BMT Jamaica Line in downtown Jamaica, which was cut back between 1977 and 1985. This section of el was eventually replaced by the Archer Ave Line.

While plans for the IND 2nd Ave Subway slogged on, even after the 3rd Ave El was dismantled, the IND South 4th St Line didn’t make it past World War 2. The 2nd Ave Subway has had many variants, but the South 4th St Line only had a few basic components, with longer-term plans being more vague.

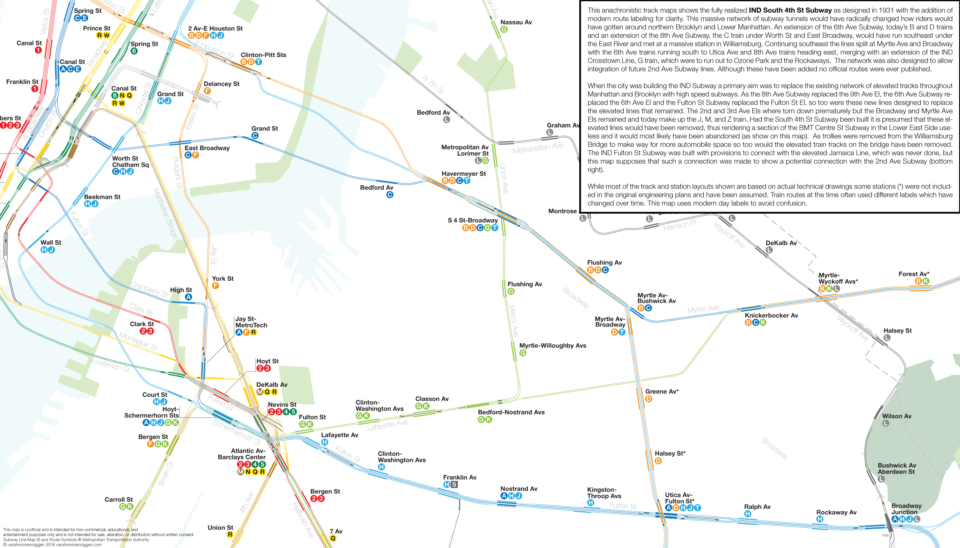

The IND South 4th St Line is the core trunk of a larger web of lines that were designed as a massive sorting machine. The original 1929 plans called for a 6-track subway along South 4th St in Williamsburg, from Havemeyer St to Myrtle Ave. The express tracks of the IND 6th Ave Line were to continue east past the 2nd Ave station and cross under the river to Grand St (Brooklyn), where they would swing down to South 4th St. Over on the IND 8th Ave Line, the line would branch off under Worth St, running up East Broadway to Grand St (Manhattan), then crossing under the river to Broadway, finally swinging up to South 4th St. Provisions would have been built for a third tunnel, which would have connected to the future IND 2nd Ave Line.

These 6 tracks would run east under a widened South 4th St, and then cut through private property between Union Ave and Beaver St. From Beaver St, the line would continue to Bushwick Ave, then split at Arion Pl, with 4-tracks of the IND Utica Ave Line turning south to Stuyvesant Ave, and 2-tracks of the IND Myrtle-Rockaway Line turning up Myrtle Ave.

Additionally, at the Bedford-Nostrand Aves station on the IND Crosstown Line, the layup tracks just east of the station would have been extended down Lafayette Ave to Broadway, then up Stanhope St to Myrtle Ave, where they would meet the IND Myrtle-Rockaway Line, continuing with 4-tracks down Myrtle Ave into Glendale. A line connecting the IND Queens Blvd Line and the IND Myrtle-Rockaway Line (the Winfield Spur) was proposed, but this seems to have been more for political support of the project rather than an actual plan.

Famously, the IND built many provisions for these lines in their first system: the express tracks and tail tracks at 2nd Ave station for the IND 6th Ave Line, and turnouts in the tunnels south of Canal St station and an unused middle level at East Broadway station for the IND Worth St Line. The Broadway station on the IND Crosstown Line has a half built, unfinished station complex at the northern end of the station where there were to be 6-tracks and 4-platforms. Even the Winfield Spur had tracks and a platform built for it at the Roosevelt Ave station on the IND Queens Blvd Line.

In essence, the combined IND Utica Ave and IND Myrtle-Rockaway Lines were to replace the remaining elevated lines of the BMT Eastern Division. Presumably, the Broadway El was to be closed, with service on the Jamaica Ave section tying into the IND Fulton St Line. Alternate IND plans suggest that this proposal was unpopular, as it would have cut off southeastern Bushwick and eastern Bedford-Stuyvesant from direct subway access. The IND Utica Ave Line would have run south along Stuyvesant Ave which is about a mile to the west of Broadway.

A larger South 4th Line plan called for keeping the Broadway-Jamaica Line, adding an eighth set of tracks to the trunk, with a terminal station built at Union Ave to support the extra trains that couldn’t fit into the East River tunnels. This alternative also moved the IND Myrtle-Rockaway Line to Flushing Ave. The Myrtle-Rockaway Line was planned to run down Myrtle Ave through Ridgewood, then out to Glendale and run along the LIRR Lower Montauk Branch until it met up with the LIRR Rockaway Beach Branch, where it would turn south and serve the Rockaways and Ozone Park. The Flushing Ave alternative, presumably, would have branched off at Flushing Ave and Beaver St, then run up to Maspeth where it would have either continued along the Lower Montauk Branch or kept running up to Queens Blvd.

The ambitions of the IND Second System were quickly extinguished when a month after it was published, the stock market crashed and sent the nation into the Great Depression. Work on the first system had only just started at that point, and it took another 11 years and millions in Federal dollars before the city could claim to have finished its subway.

The high costs of the new lines caused planners to quickly rethink their long term plans. The IND was legally required to make money within 3 years of opening, so planning new lines based on existing transit corridors was simple enough. But planning new lines into the farms of eastern Queens proved more difficult. The IND Myrlte-Rockaway Line was designed as a trunk line for branches into Ozone Park, South Jamaica, and the Rockaways. With exploding costs, these areas, which were still relatively underdeveloped at this time, would not be able to support the massive investments needed. Ironically, eastern Queens did see massive development after World War 2, but this was due to the rise of the car and highways.

Very quickly, the IND Myrtle-Rockaway Line was dropped entirely. The planned branches were instead grafted onto an extension of the IND Fulton St Line, whose route had finally been finalized by 1937. The proposed IND Rockaway Line itself (which, at this point, was still and active LIRR branch) would connect to the IND Fulton St Line in Ozone Park and provisions for a connection to the IND Queens Blvd Line were built in Rego Park.

The IND South 4th St Line hung around a little while longer as it was still the norther section of the proposed IND Utica Ave Line. It wasn’t until after World War 2 that transit planners finally dropped the IND South 4th St Line entirely, opting to return to the original Utica Ave proposal, a branch off of the IRT Eastern Parkway Line. Even that remains a dream deferred today.

Broken Network

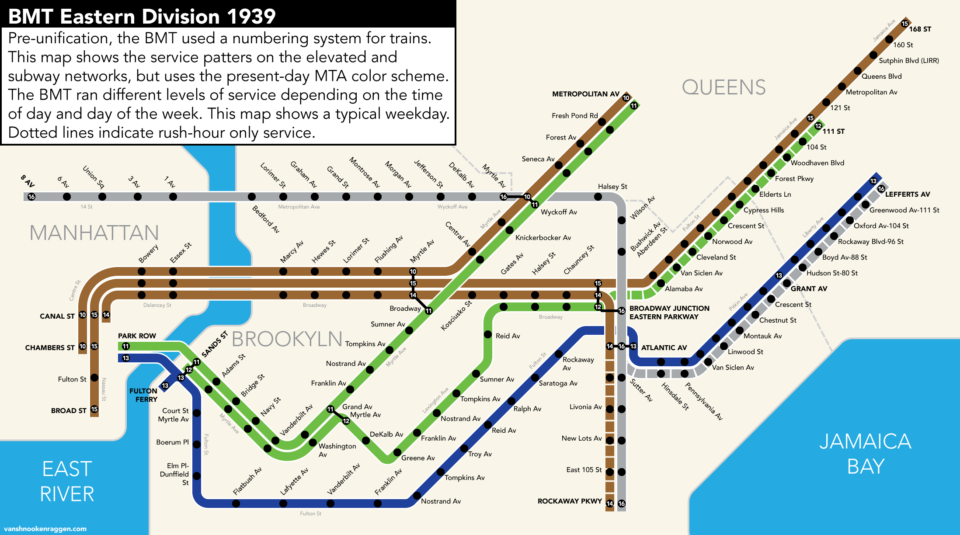

The problem with designing such an extensive network of lines is that when you ultimately only get to build part of the plan, the entire network suffers from missing the unbuilt parts. The BRT Eastern Division was not just a series of elevated lines, but an integrated network that worked together. At its height, the dual stations at Broadway Junction and Atlantic Ave sorted seven different routes, allowing riders one seat rides from southern Queens and east Brooklyn to Midtown Manhattan, Lower Manhattan, and downtown Brooklyn.

The BRT had divided its network into two sections: The Southern Division and Eastern Division. The Southern Division, as the name would suggest, connected southern Brooklyn (mainly Coney Island) with downtown. The Eastern Division was named so because it ran to the east of downtown.

The Eastern Division was in essence four branches: Myrtle Ave, Jamaica Ave, Liberty Ave, and Canarsie. Today the Myrtle Ave Line is served by the M train, the Jamaica Ave by the J/Z trains, the Liberty Ave by the A, and the Canarsie by the L. Because branches split service, today’s M, J/Z, and A trains all run with long headways and less than optimal service. The BRT solved this with a series of reverse-branch lines.

The Myrtle and Lexington Ave Els provided double the service on these branches. Myrtle Ave riders could take one train to Lower Manhattan or one to downtown Brooklyn. Jamaica Ave riders could take one train to Lower Manhattan via Broadway, or downtown Brooklyn via Lexington Ave. Liberty Ave riders could take one train to downtown Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan via Fulton St, and at rush hour take a train to Midtown via the 14th St-Eastern Division Line. Canarsie Line riders could take one train to Midtown via the 14th St-Eastern Division Line or get to Lower Manhattan via Broadway. Reverse branching has its problems; namely, when one train is delayed, the delay ripples on to other lines, which then ripple throughout the system. But reverse branching offers more service and more options for riders.

It wasn’t just money that ended the dreams of the Second System. Central Brooklyn, like many other parts of the city, began to see a massive population shift after the War. The former working class neighborhoods of Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant that were home to European immigrants began to change as those residents moved out to newer homes in Queens and Long Island. The new residents, often Puerto Ricans and Blacks from the deep south, came to New York looking for manufacturing jobs, which were now leaving the city as well. Neighborhoods along the Myrtle Ave and Broadway Els began to spiral into poverty.

Had they been built, the new subways wouldn’t have stopped this wave from crashing. The IND Fulton St Line had opened in 1936 and been extended to Euclid Ave in 1948. Bedford-Stuyvesant and East New York only slid deeper into poverty. As residents moved out, ridership plummeted. The Myrtle Ave and Lexington Ave Els were removed between Broadway and Jay St, and trains on the IND Crosstown Line were shortened to save money. Even today, the platforms of the J/Z, M, and L trains are all only 8-cars long when the platforms of all other B Division lines were extended to 10-cars long ago.

With the opening of the IND Fulton St Line extension to Euclid Ave, the city was finally able to remove the last sections of the old elevated tracks from Rockaway Ave to Euclid Ave. Where there was once a relatively simple cross-platform transfer at Atlantic Ave to trains on every line, riders would not be forced to make the legendary transfer at Broadway Junction with a new set of stairs and escalators. The Atlantic Ave station was dramatically cut back, and much of the elevated structure has been cut back over the decades.

Centre St

Even Manhattan was not immune to the loss of Brooklyn el service.

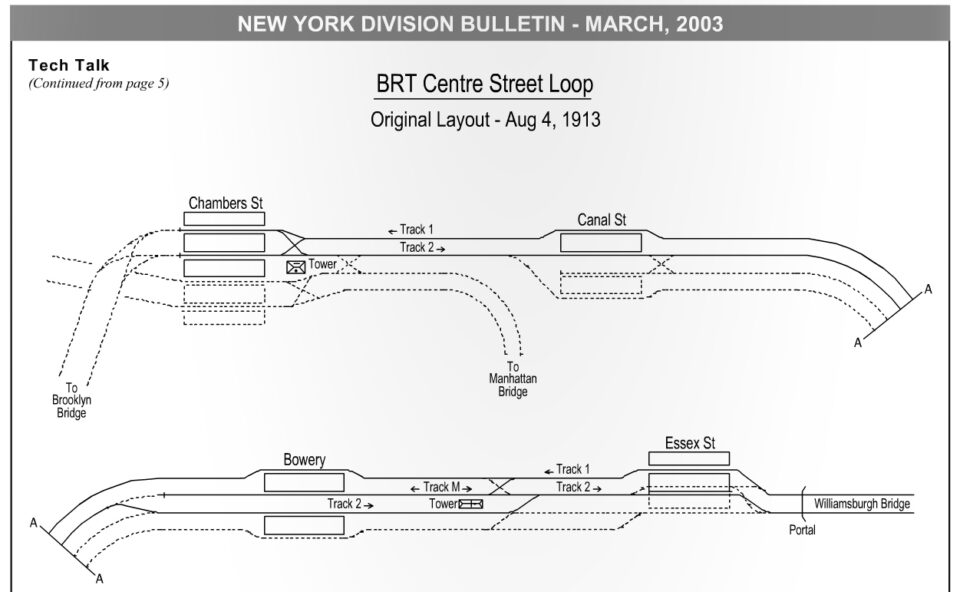

The Centre St Line, which extended the Williamsburg Bridge tracks from Delancey St to Chambers St, was one of the first subways planned as part of the Dual Contracts. When the Williamsburg Bridge was built, a branch of the Broadway Line was extended over the bridge into a subterranean terminal at Delancey and Essex Streets in the Lower East Side. This terminal served both elevated trains and streetcars. The new Centre St Line connected this terminal to a new 4-track subway to City Hall.

The Centre St Line went through a number of changes, as subway service over the new Manhattan Bridge had not yet been developed. Bridge service was initially to be a simple crosstown line running down Canal St, terminating at West St. Plans evolved to what was eventually built: the Brooklyn Loop Line. Trains off of the Williamsburg Bridge were to run down Centre St and then loop back into Brooklyn over the Brooklyn Bridge, while trains off of the Manhattan Bridge were to loop back along Nassau St and return to Brooklyn via a new tunnel under the East River.

The tunnel was built between Whitehall St in Manhattan and Montague St in Brooklyn, though the Nassau St Line and tunnel connection was not built until the 1930s. The connection to the Brooklyn Bridge was discarded, as the the sharp grade between the subway and bridge would have required using more powerful trains that would have been too heavy for the bridge to support.

Lower Manhattan was one of the densest places on the planet when these lines were built. Commerce, shipping, and manufacturing were all on top of one another, surrounded by tenements teeming with newly arrived immigrants. The subways were specifically designed to decongest these areas by allowing workers to move out of the slums and commute to work from new developments uptown and into Brooklyn. As time went on, this worked too well. The subways opened up vast stretches of the outer boroughs to development, but it also shifted the center of commerce. By the 1950s, Midtown was growing and the manufacturing jobs of Lower Manhattan were leaving the city all together.

The 4-tracks of the Centre St Subway are often misidentified as express and local tracks. In actuality, they were for terminating and through-running trains. Centre St allowed trains to terminate that were not going to loop back into Brooklyn. The center tracks ended at Canal St, while the outer tracks ran through to Nassau St and back into Brooklyn. The massive Chambers St Station, which features four tracks and, at one point, five platforms, is not an express stop as we think of one today but was simply two stations placed side by side, with two tracks intended on looping back over the Brooklyn Bridge and two going down Nassau.

With less ridership, this extra level of service was too expensive to run and was eliminated. To save money, the two southern tracks of the line were eventually closed entirely (closing their respective platforms as well) and the tracks which once ran downtown were relocated. In 1967 the tracks here were realigned so that trains that would formerly have looped back into Brooklyn would now continue on to Midtown, forever disconnecting these extra tracks from service. The MTA continues to use them for storage, film locations, and even a fashion show.

Archer Ave

There was one section of the old el network that was successfully replaced with a subway. In the 1960s, at the behest of Jamaica business leaders and politicians, the city began to plan for the replacement of the Jamaica Ave El through the heart of Jamaica. What we know of as the J today once ran to 168th St. The city was worried about white flight, and much like the IND Fulton St Line before it, thought that replacing the el with a subway would reverse this trend.

The plan involved rerouting the BMT Jamaica Line from Jamaica Ave to Archer Ave (which at its closest is 300 feet to the south), along with building a connecting to the IND Queens Blvd Line using a provision for the unbuilt IND Van Wyck Blvd Line. Archer Ave was designed to have J trains terminate at 168th/Archer Ave and Queens Blvd trains extend southeast along the LIRR Atlantic Branch to Springfield Blvd.

A groundbreaking was held on August 15th, 1972. At the time, the MTA had been promoting its ambitious Plan for Action, the largest transit expansion plan since the IND Second System. The city was also building the 63rd St Tunnel and 2nd Ave Subway. But it soon became clear that the costs of these projects would be much higher than the MTA initial thought, the condition of the subways was far worse than previously understood, and the toll revenues from the bridges and tunnels wrestled away from Robert Moses were nowhere near enough to cover everything.

The city was grappling with the fact that its debts were growing, and its tax base was leaving. In 1974, the MTA was able to win a $51.1 million ($380 million in 2023) grant from the Federal government for Archer Ave construction. Soon, Mayor Abe Beam announced that he was cancelling the 2nd Ave Subway. Work on the 63rd St Tunnel and Archer Ave would continue because the MTA had already spent the Federal money, which would need to be returned if the projects were cancelled.

While the city could not afford to keep building these lines, it could also, literally, not afford to stop.

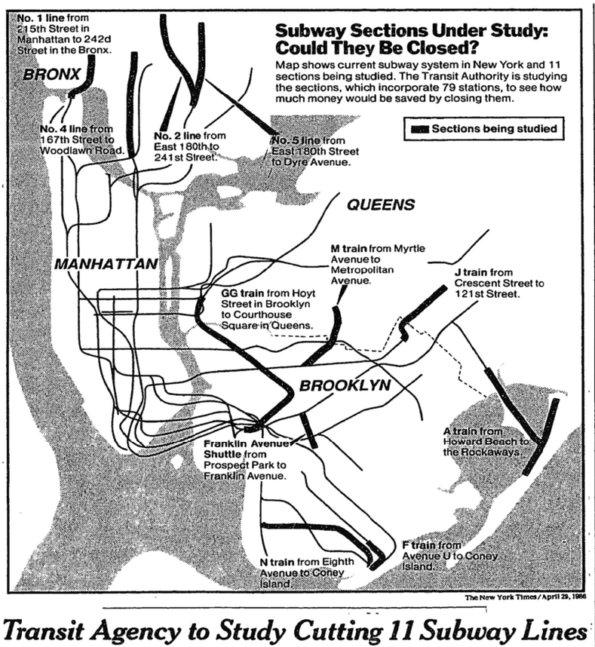

In the 1970s the city faced an unprecedented fiscal crisis. The state of New York had taken away the subways from city control in 1968 due to the city’s inability to property fund and maintain them. At its lowest point in the 1980s, the MTA considered eliminating a number of lines, including the entire Myrtle Ave Line and the Jamaica Line east of Broadway Junction.

The report was more of a scare tactic to raise funds rather than a real plan. Ultimately, the state and city agreed to fund the MTA’s new Capital Program which aimed to bring the system to a state of good repair by 2007. Investing in the system, along with greater economic shifts, helped bring people back to the system and ridership began to grow.

In the end, it was investing in the elevated lines rather than replacing them, which proved to be the right choice. While the remaining els still present the same quality of life issues that they always did, they nonetheless provide an incalculable value to the city overall. Even the hottest waves of gentrification the city has ever seen are no match for the iconic el train.

Work on Archer Ave continued slowly and in 1977 the Jamaica Ave El was cut back to Queens Blvd. Many thought that this would be a repeat of 2nd and 3rd Aves, which saw their els removed before a subway could be built to replace them. In 1985 the line was cut back to 121st St in preparation for a new subway portal to be built alongside of the LIRR Main Line. This connection between the subway portal and 121st station is the last time a traditional elevated structure was built for transit in New York.

The Archer Ave Line opened in December 1988, many years late and greatly over budget. But for the first time since 1940, an elevated train had been successfully replaced with a subway.

If you know where to look, you can see the ghosts of the pre-subway els in the Bronx and Brooklyn. All elevated lines that remain in Manhattan and Queens date from the Dual Contracts and don’t have as much of the lost infrastructure that is really the focus here (although, as you can see in the opening image, Queensboro Plaza used to be twice as large). I wanted to focus mostly on the Broadway El, as it’s the dinosaur of the system. In my next post, I’ll delve deeper into historical upgrades that the city has tried to make into the Jamaica Line, and some potential enhancementsthat would greatly improve service for relatively cheap. There will also be a long term plan which reenvisions the IND South 4th St plan for the modern day.

Well researched and written. I think replacing current El structures with the type of El structure used on western portion of the Philadelphia’s Frankfort Market Street line is a possible solution. That quieter type of El could be employed to expand service into the lower density areas of the city.

I agree, but the stigma exists and it’s going to be a hard sell.