I hadn’t intended on revisiting the Southeast Queens Line after my two part series. But in researching Jamaica transit, I found myself down a rabbit hole looking at the IND plans in Jamaica. This post is therefore a prequil to those posts.

Subway service first reached Jamaica in 1918. Previously, Jamaica had only been served by the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) and, later, streetcars. There had been a hybrid elevated-streetrunning service which allowed Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) riders a one-seat-ride from the East River ferry to Cypress Hills via the Broadway El. Then, using a ramp, trains would continue on to 168th St along Jamaica Ave. Traffic slowed down the trains so much that this practice was cancelled, to be replaced with an extension of the elevated line in 1918. The BRT Broadway Line thus became the Jamaica Line.

With the introduction of subway service directly to Manhattan, the former farms of Queens began to be subdivided into bedroom communities. The Jamaica Line served an existing market of mostly bedroom communities flanking the LIRR Atlantic Branch. Thanks to the success of the new IRT/BRT Astoria and Corona Lines (which is how the 7 train was known as before its extension to Flushing), areas north of the glacial moraine were developing as well.

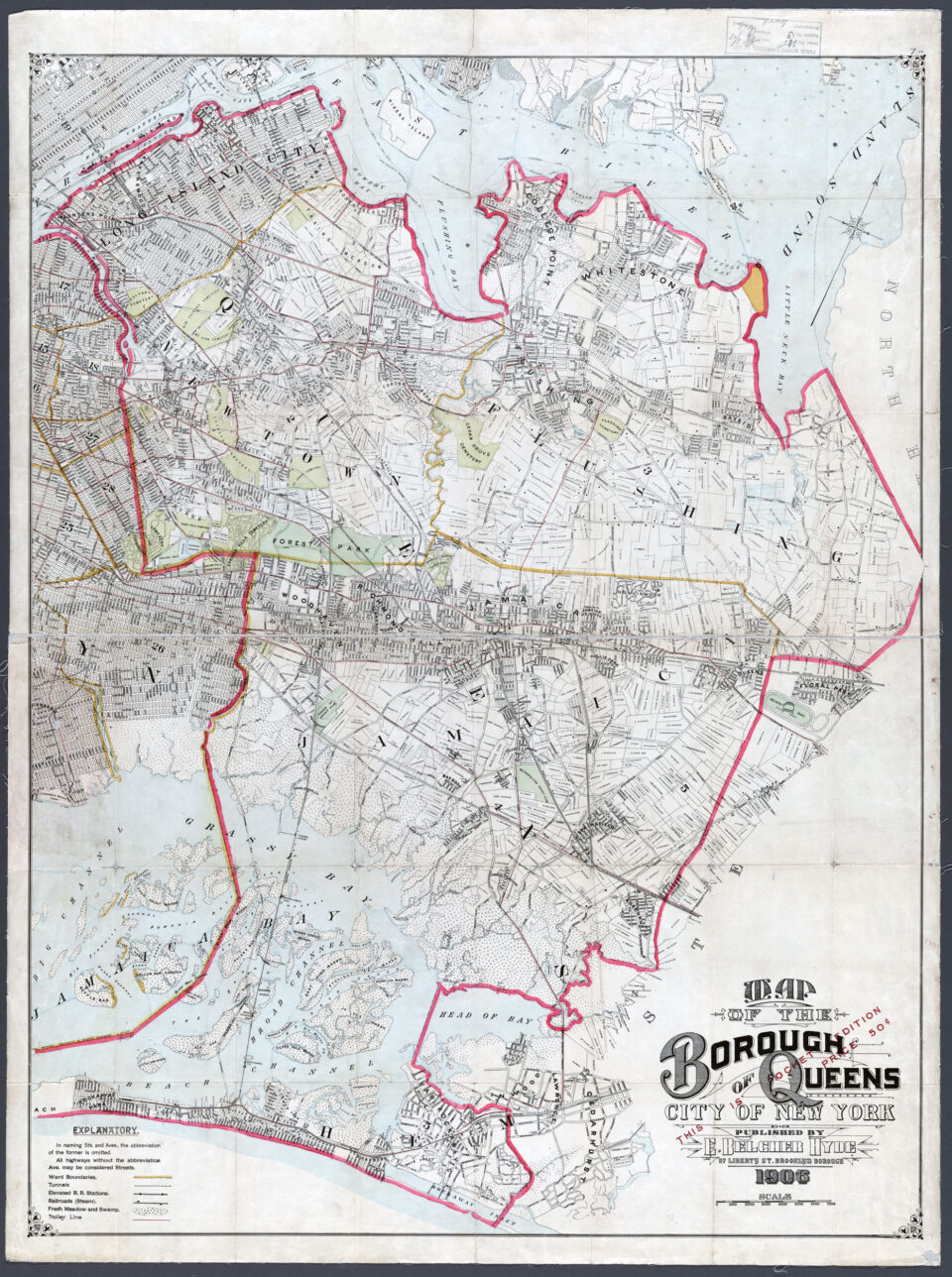

Queens, having never been an incorporated city, but rather a collection of towns, never planned its growth in the same way that New York and Brooklyn had. In 1898, Long Island City and the towns of Newtown, Flushing, Jamaica, and the Rockaways (which were part of the town of Hempstead) voted to join the City of Greater New York. Hempstead and Oyster Bay elected to stay separate, and the county of Nassau was created for them. Queens has its famous overly compicated numbered street system due in part to the original town having the same street names in completely different places.

The selling point for this union was infrastructure. Long Island had a small and finite aquifer system, but New York City, with its Croton Aqueduct system, had seemingly limitless water. New York could also build roads, bridges, and after 1904, subways to link the far-flung towns together with the growing city. In 1901, the Queensboro Bridge became the first grand connection between the boroughs, followed by the city laying down new streets and highways.

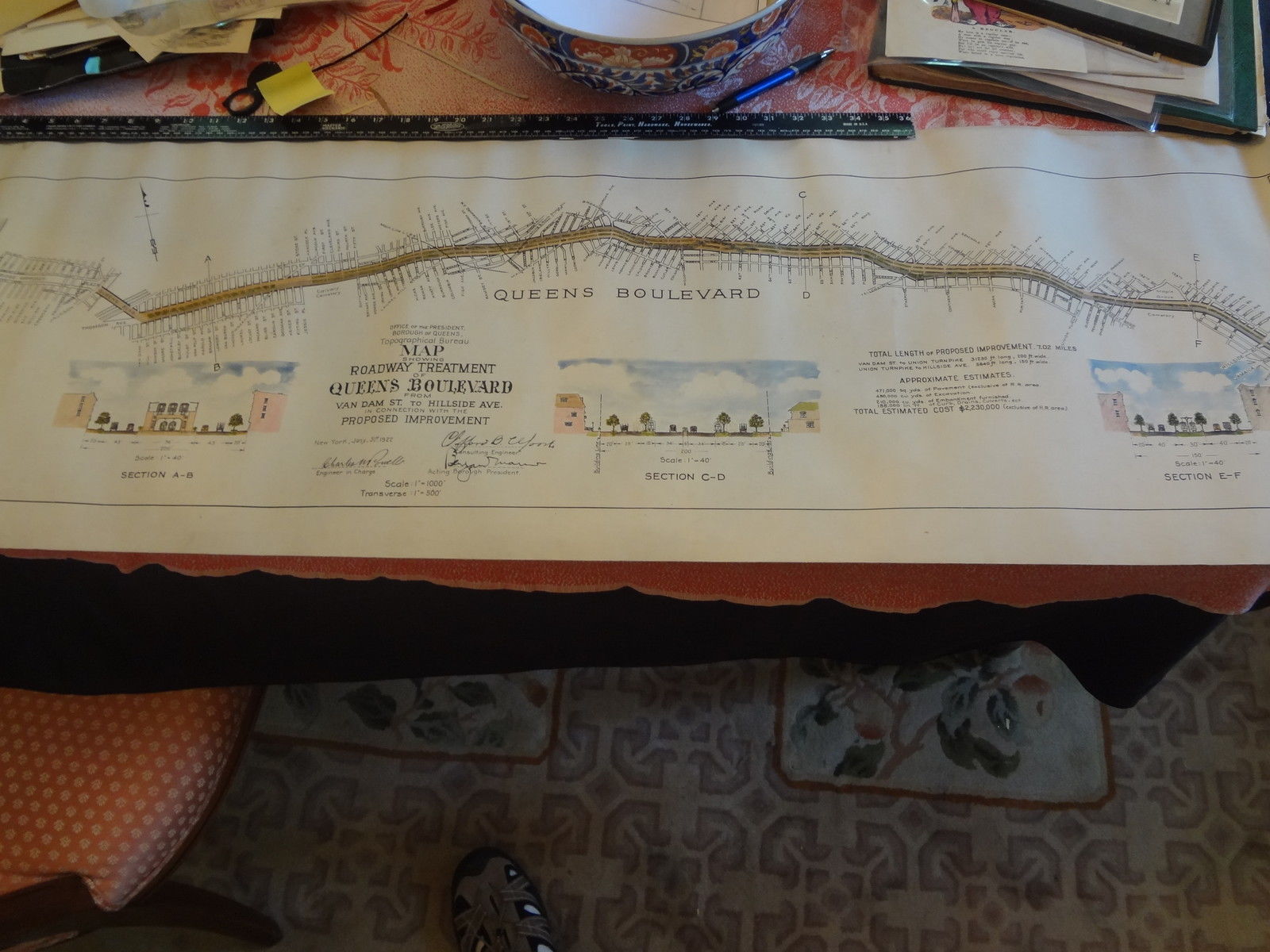

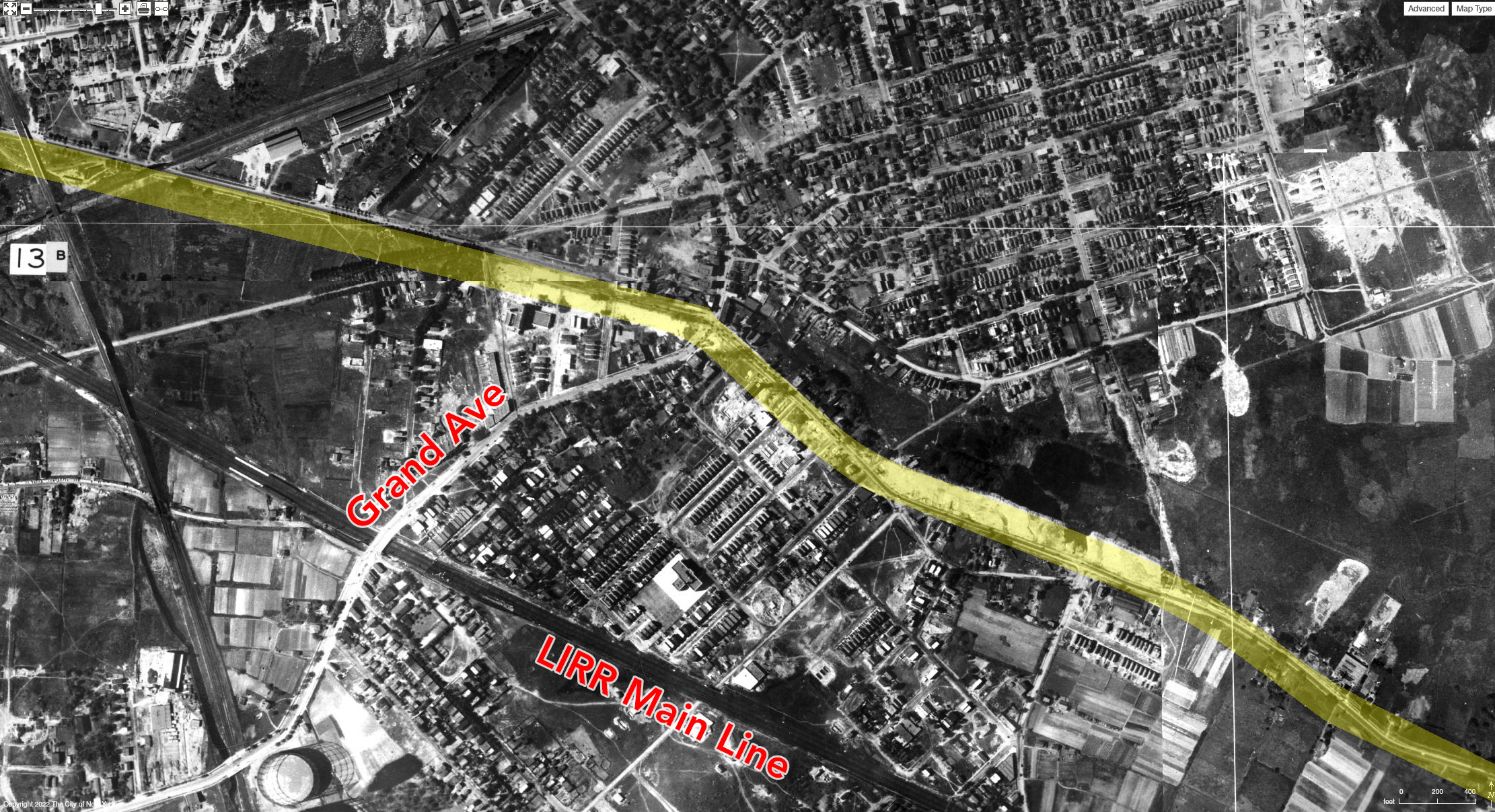

Growth brought more growth. The Dual Contracts had brought new subway lines into the borough, and the city began planning a new grand boulevard that would connect New York, via the new Queensboro Bridge, to Jamaica. This highway was envisioned as a compliment to the Grand Boulevard and Concourse, built in the Bronx between 1894 and 1907. The aptly named Queens Boulevard was designed with similar features: center through-lanes, flanked by local service roads which were separated by landscaped medians. Streetcars, which would use an underground terminal on the Manhattan side of the Queensboro Bridge, would run along the medians.

The first section, from Van Dam St to 48th St in Sunnyside, was built as part of the new Corona Line. Even today, this section of the subway is a great example of the value city builders put on new infrastructure. The concrete viaduct running down the median of Queens Blvd is an icon of both the borough and city in general.

Building Queens Blvd did not happen overnight. Much of the route was cobbled together out of existing roads, often two lane dirt roads which, only recently, had been traversed only by farmers bringing their stock to the city, pulled by horses. By the time Queens had been connected to the city, the car was quickly making its presence known.

At the time, the route of Queens Boulevard connected a collection of small developments with names that are all but lost to history now. Winfield was a relatively dense settlement which was located southeast of the present Woodside. The name lives on only for railfans (Winfield Junction is where the LIRR Port Washington Line branches off of the Main Line) and the members of St Mary’s Winfield Catholic Church at 47th Ave and 72nd St. Newtown was an incorporated town like Flushing and Jamaica, but today it’s been devoured by more modern names like Jackson Heights and Elmhust. Only those students who attended Newtown High School have any reverence to the name (although, if you are a true student of New York history, I recommend going out to see the Reformed Church of Newtown on Broadway and Corona Ave, now home to a Chinese denomination.)

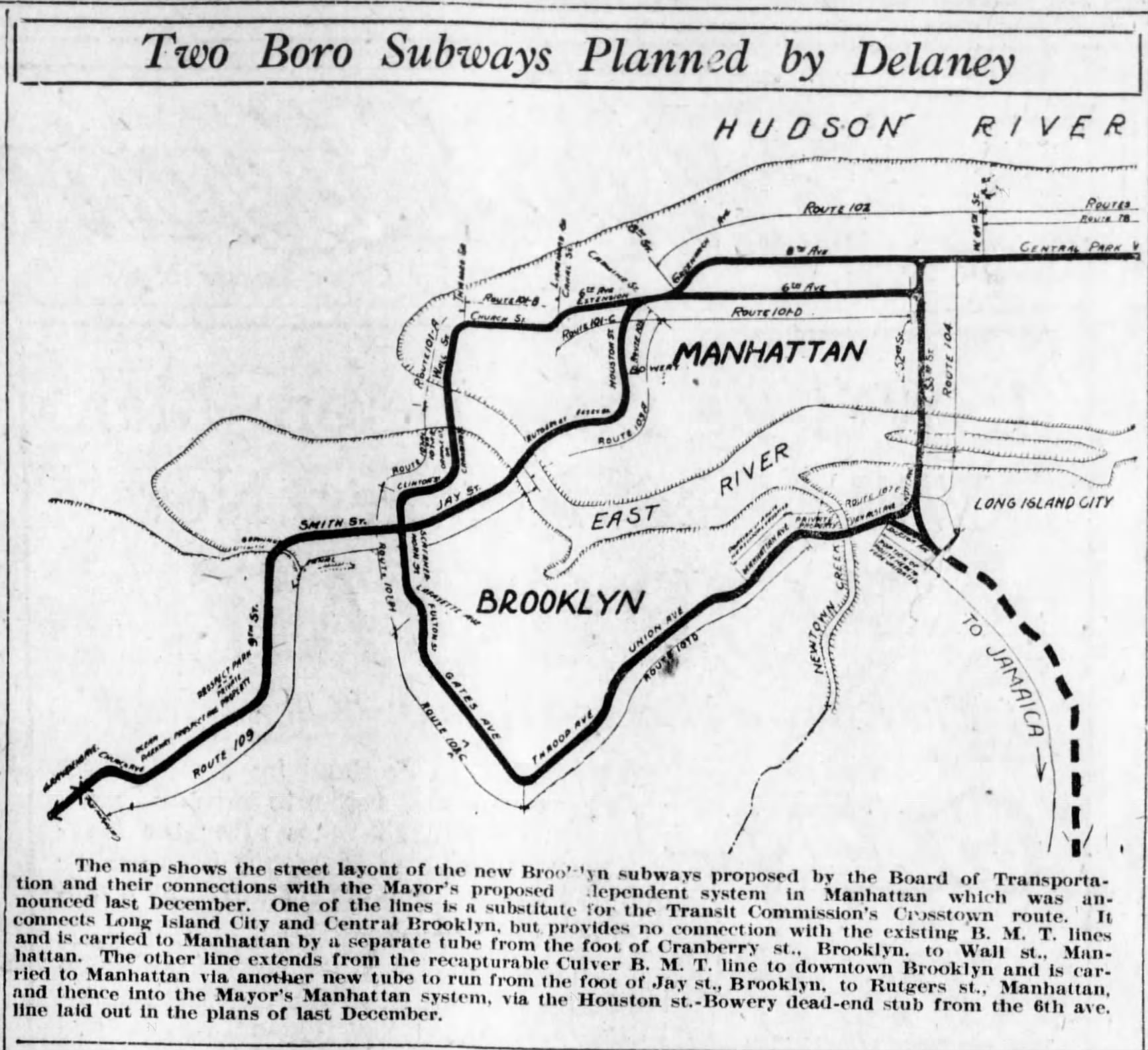

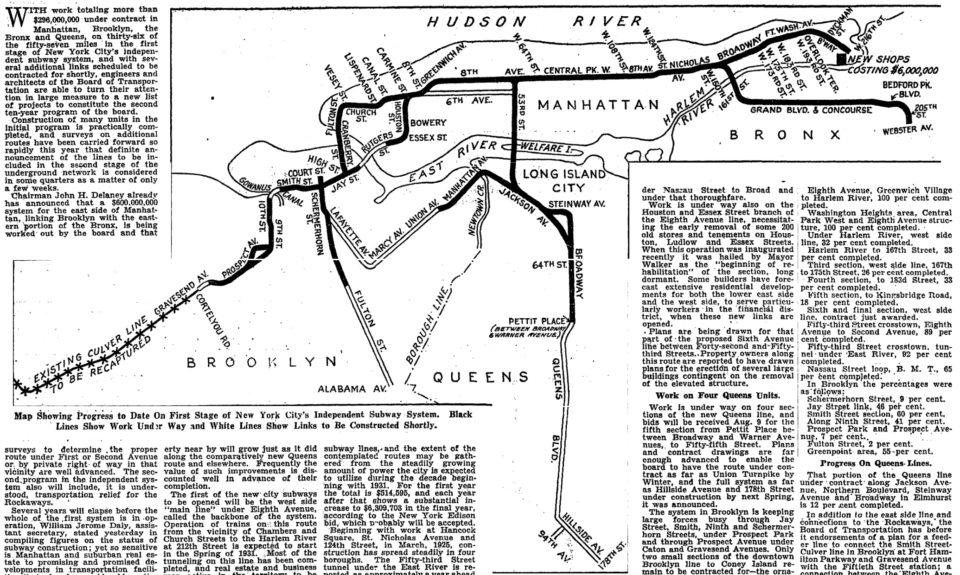

At the same time that the boulevard was being built, the city was embarking on a new round of subway building. Mayor John Hylan had chosen to block both the IRT and BMT from expanding in favor of building his own, city-run subway. This new system, the Independent System (IND), would be responsible for building the planned 8th Ave and Crosstown Lines. These lines had been first proposed in 1912. Many of the 1912 plans were focused on Manhattan, the Bronx and Brooklyn. Queens had only begun to develop and the city hadn’t planned any new subways for the borough.

Pre-IND subway plans had proposed extending the IRT Corona Line (which wouldn’t be extended into Flushing until 1928) to 8th Ave, then connecting to the 8th Ave trunk line. Running south, it would either connect back with the BMT 14th St-Canarsie Line, or continue south to Lower Manhattan. No mention was made about the difference in train car widths between the two lines. This proposal would be built upon by the IND, which proposed their own Queens Line to connect with their 8th Ave trunk line at 53rd St.

The early focus for the IND was on 8th Ave and the Crosstown Line running through Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Bed-Stuy, Fort Greene, and downtown Brooklyn. The initial concept was for this line to loop through Manhattan via the 8th Ave Line, and later the 6th Ave Line (a dual avenue trunk line had also been proposed back in 1912, and the IND finally put it into the design in 1925). The new East River tunnel between 53rd St and Long Island City was originally proposed to be 4-tracks wide, with 2-tracks continuing deeper into Queens, and 2-tracks looping through Brooklyn. The Crosstown Line would also branch into Queens, connecting Brooklyn and Queens.

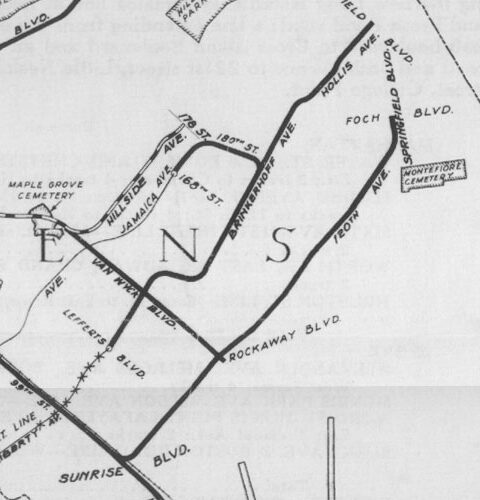

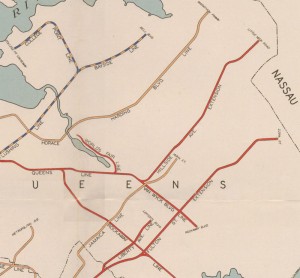

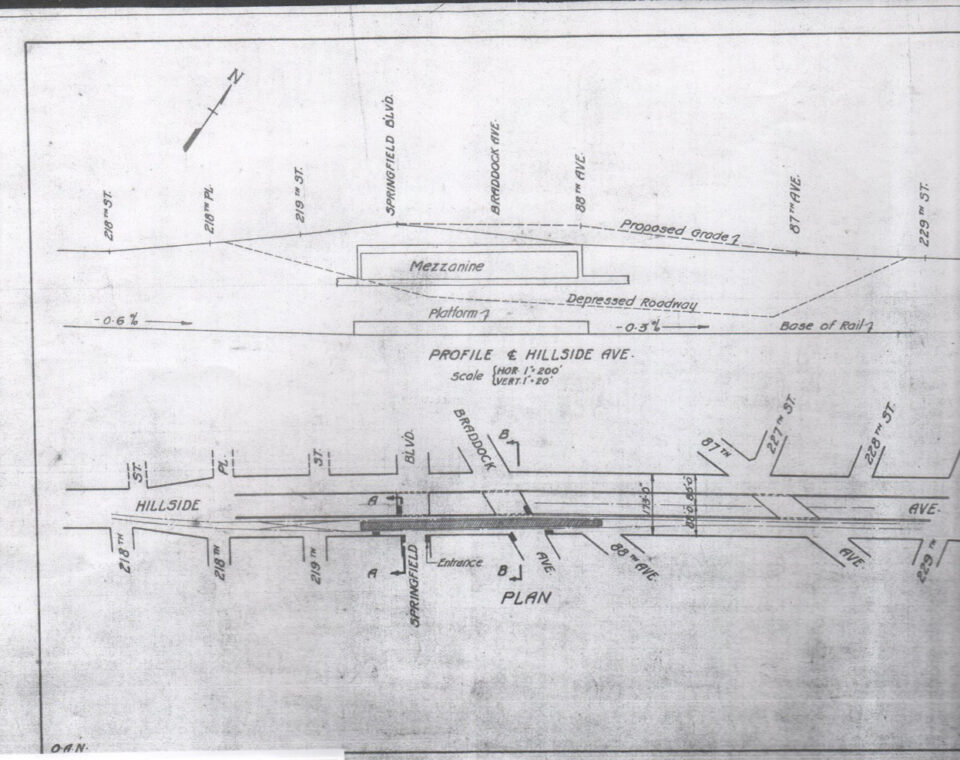

By 1925, the city had decided on the route for most of the new Queens line. From Long Island City, the 4-track line would run up Jackson Ave to Northern Blvd. At Steinway St, the local tracks would diverge: the local tracks were to run up Steinway St and turn east under Broadway while the express tracks were to continue along Northern Blvd until Broadway where both would link up again. From here, Broadway would be extended through Woodside to Newtown. At 69th St, the local tracks would diverge once again, turning south under 69th St, while the express tracks would continue east under Broadway. The local tracks would turn east at Queens Blvd. Both lines would meet up again where Broadway curves south and meets Queens Blvd at Grand Ave. The 4-tracks would continue heading east until they reached Union Turnpike, at which point the lines would split for the final time. The local tracks would turn off of Queens Blvd and run along Kew Gardens Road, skirting the southwestern border of the Maple Grove Cemetery, until it reached Hillside Ave, where it would turn northeast and run along Hillside Ave until 178th St. The express tracks would continue along Queens Blvd until Van Wyck Blvd, at which point they would cut through private property under the neighborhood of Briarwood, making a direct line to Sutphin Blvd, running south to Archer Ave and the LIRR station at Jamaica.

In Brooklyn, the IND planned to build a line south to Coney Island by recapturing the BMT Culver Line which had been build during the Dual Contracts. When the Fulton Line was added to the mix, the added service required for the new lines meant that space for the Crosstown Line to enter Manhattan had to be sacrificed. The 53rd St Tunnel was reduced from 4-tracks to 2-tracks, eliminating the ability for the Crosstown Line to directly reach Manhattan. Service on both the South Brooklyn (today, the F/G) and Queens Blvd Lines would be limited so that only the express tracks being able to cross into Manhattan.

When New York City had been confined to Manhattan Island proper, all elevated lines had terminated at the tip of Lower Manhattan. When the subways were built with the new local-express concept, they were designed so that the local tracks would continue to terminate in Lower Manhattan, while the express trains crossed into the outer boroughs. This pattern had been similar for Brooklyn elevated trains, with some terminating at the banks of the East River, and some crossing over the new bridges as they went up.

The IND figured this could work for their subways as well. By connecting the South Brooklyn local tracks and the Queens Blvd local tracks directly to the Crosstown Line, the IND could kill two birds with one stone. Express trains on both lines would run into Manhattan, but the locals would stay between Brooklyn and Queens.

As planning progressed, the Winfield diversion along 69th St was cut. The odd route had been chosen due as a way to serve already developed areas, so that ridership would be higher. But the reality of building two lines instead of one meant it would also cost more. Extending Broadway through Elmhurst and compensating landowners drove the cost of construction up, so the tunnels were simplified along one route.

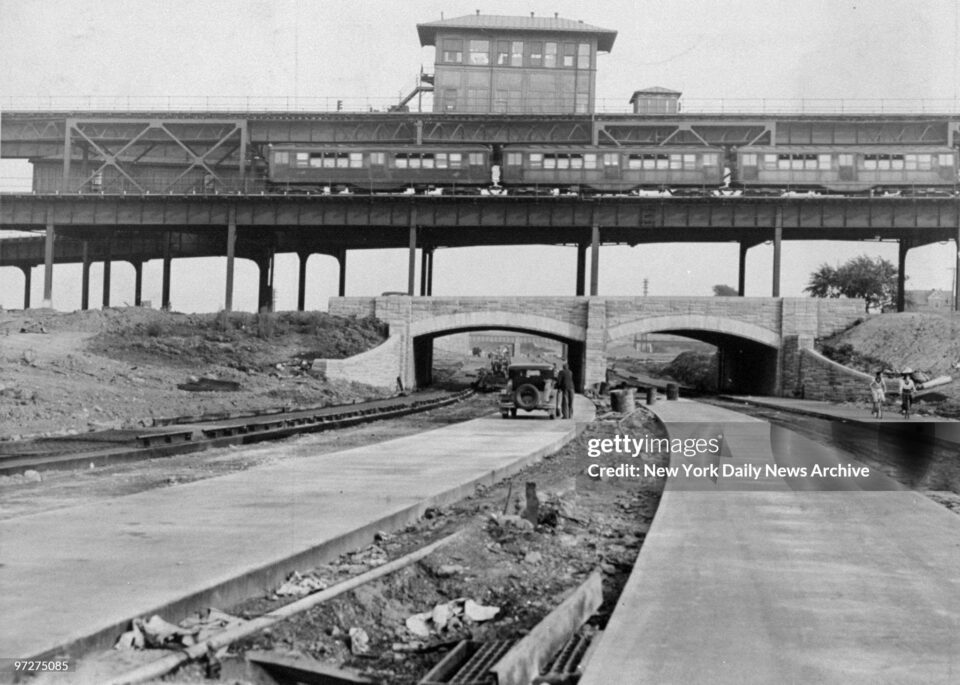

The initial design of Queens Blvd was closer to that of Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn. By the time the IND began digging the Queens Blvd Line in 1927, the art of highway building had evolved to include large over and underpasses for major roads to separate through traffic from local traffic. Queens Blvd, being built with center through-lanes and outer local-lanes, would take advantage of this new design by lowering the center lanes as the road passed the newly built Woodhaven Blvd and Horace Harding Blvd, both of which were new arterial highways knitting the borough together. The Queens Blvd tunnels were built with these underpasses in mind; The 4-track subway runs under the center lanes of the road, and are far enough below ground that these lanes could be lowered if need be.

Van Wyck Blvd Line

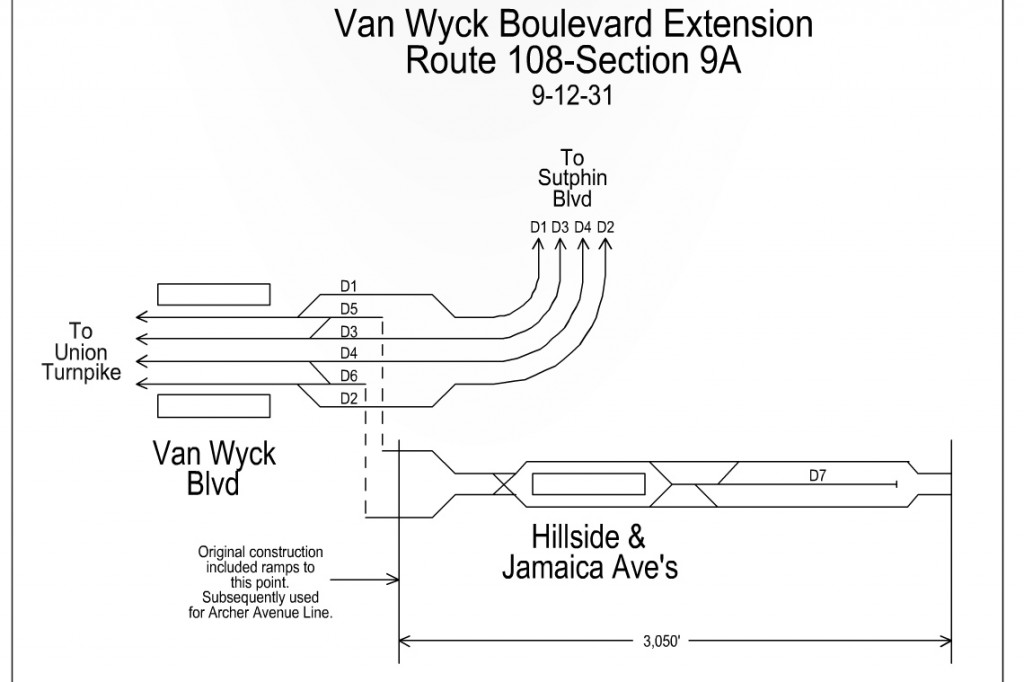

Plans evolved and were finalized as construction began. In Kew Gardens, the two branch split was redesigned so that the 4-track trunk line continued along Queens Blvd only, turning south at Van Wyck Blvd, before turning east at Hillside Ave. When the tunnel turned east, two tracks would branch off and turn south, as per the original plan. But instead of using Sutphin Blvd, the branch would run south along Van Wyck Blvd.

In 1929, a group of local business and civic leaders held a public meeting to debate the plans, and 600 residents showed up. The Sutphin Blvd supporters claimed that it made more sense to serve the LIRR station, which had helped create a commercial center. Chairman of the Board of Transportation John Delaney (which was the city agency planning and building the IND) responded that Sutphin Blvd already had transit facilities, and that the Van Wyck alignment would serve more of Jamaica, which was lacking transit. The choice came down to what would be easier to construct, and running the new line under an existing road was easier, and cheaper, than cutting across private property, whose owners would need to be compensated‘.

Once the IND had settled on the route, a local booster began a campaign to get the branch along Van Wyck Blvd included in the next round of subway extensions. Joseph A Coyle was the president of the Dunton Civic League. Dunton is another neighborhood name lost to history, but existed around the area of 134th St and Van Wyck Blvd (hence the strong support). Coyle, who was once described by Mayor Jimmy Walker as a “Little Napoleon of Civics”, made it his mission to promote the line. Between 1929 and 1940 would write letters to any newspaper that would print them, hounded John Delaney, and even petitioning Mayor LaGuardia on the issue. Dunton claimed that the subway would support itself through real estate development.

The short spur along Van Wyck Blvd to Atlantic Ave had always been included as part of the initial IND system. As construction went on, local civic groups began asking the city for new lines. This lead the IND to release an expansion plan to build support for new lines. As part of their IND Second System from 1929, the city proposed extending the Van Wyck Line further south to Rockaway Blvd. This gave fuel to supporters of the line, and advocates like Coyle soon began pressing the city build not just the short spur to 94th, but move forward on the entire line south to Rockaway Blvd.

It seems that, like so many of the expansion plans from the time, the Van Wyck Line was built only on wishful. As the Depression went on, the IND struggled to complete what it had started and looked for ways to save money. The original Van Wyck Line was to include a single station at Jamaica Ave, with tail tracks to Atlantic Ave. The station and tracks were cut, leaving only a partially built junction where the main Queens Blvd Line makes a turn east under Hillside Ave. Claiming that the line would be built as part of the next phase was simply a way of creating support for the next time the city had to ask for more money.

Hillside Ave Line

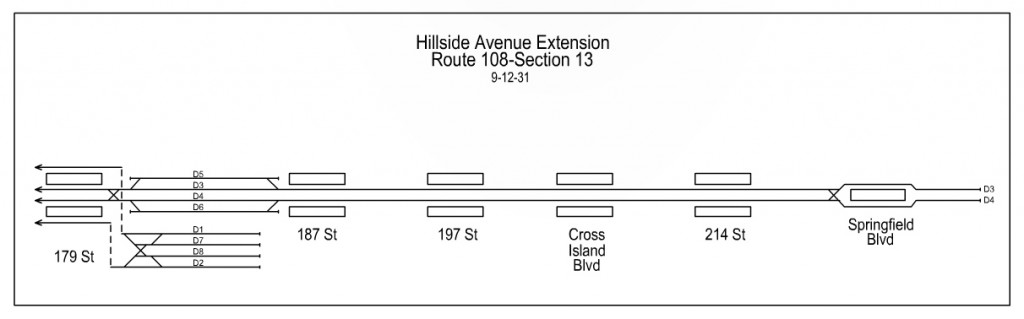

The IND was feeling pressure from other civic groups on the north side of Jamaica as well. The Hillside Ave Line had been planned to run to 178th St. The commercial area of downtown Jamaica was, at the time, centered between Parsons Blvd and 168th St. The original LIRR Jamaica station had been located at what is today Union Hall St, at the center of this area. Running the IND along Hillside Ave to 178th St meant that they could capture the northern half of downtown traffic, while also giving themselves a wider highway under which to build. Jamaica Ave is the only other fully East-West road in the area and already had an elevated train running over it.

Now, if you told the average person that the city was building a subway to 178th St, specifically, you could forgive them for thinking this meant that the last stop would be 178th St. But the IND was a bit odd. The maps which were published at the time drew the lines of the new tunnels right up until the very end of the tunnel, even when there wasn’t a station there. So, while the IND was building their new tunnel under Hillside Ave right up to 178th St, that didn’t mean that there was going to be an actual station at 178th St.

Once this was realized, civic leaders (and especially real estate developers) from areas north and east of downtown Jamaica (namely Jamaica Hills, Hollis, and even Queens Village) were up in arms and began petitioning the IND to build a station at 178th St. One local leader even claimed that a “temporary” station could be built until the IND extended the line further east. John Delaney claimed that a station at 178th St would be part of the next phase. As with the Van Wyck Line, it became useful to promote the extension of the Hillside Ave Line from 178th St to Springfield Blvd to build support for finishing the first phase.

Initial plans called for a 2-track extension to Springfield Blvd. But a later plan called for a 4-track extension to Springfield Blvd, then a 2-track extension to Little Neck Parkway as a future phase.

Like so many things with unbuilt subway plans, it all came down to money. The IND had begun building their system from Manhattan outward. The 8th Ave trunk line opened in 1932, and the first section of the Queens Line (8th Ave to Roosevelt Ave) and Crosstown Line (Nassau Ave, Brooklyn to Roosevelt Ave, Queens) had opened in 1933. Much of the construction of the initial system had ended up costing far more than was anticipated, and the city was soon to begin paying the interest on their bonds. The promise of expansion kept people buying bonds, and kept the money coming in.

The mythology of the New York City Subway is that it used to cost a nickel. The 5 cent fare was baked into the contracts with the IRT and BMT. Riders expected the same of the new city-run lines. But early on, it was clear that the system could never pay for itself on 5 cent fares. Because of the higher interest rates, the city would need to charge 7 or 8 cents to cover the debt service. The mayor refused to charge more than 5 cents, seeing that as political suicide. Once the subways began to run, they lost money, and construction ground to a halt.

Mayor LaGuardia had a special relationship with the new President, former New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt. Through Works Progress Administration loans, set up to get men back to work, the Mayor was able to finding the funding necessary to finish the subways currently under construction: the Crosstown Line, Fulton St Line, and Queens Blvd Line. The Queens Blvd Line was opened to 71st Ave-Continental Ave in Forest Hills in 1936, and a year later it was opened to 178th St, with the final station at 169th.

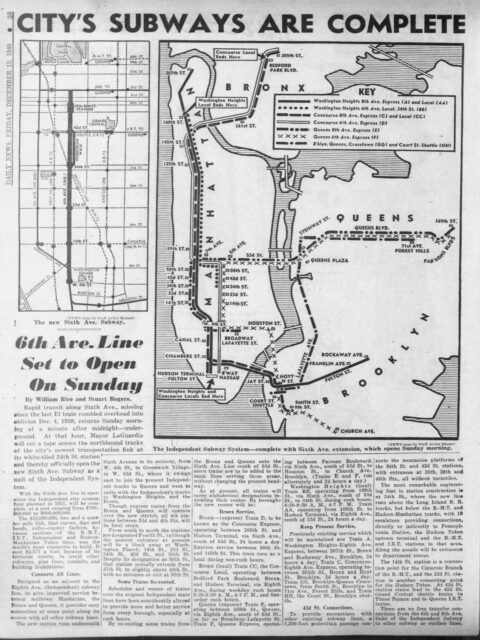

6th Ave Line

Because of the limited funds, the Van Wyck branch and 178th St station had been pushed back until the next phase of work. But these lines still wouldn’t have been useful without added capacity within Manhattan, as the 8th Ave trunk had filled up with service from the Bronx and Queens. The 6th Ave Line was needed to open capacity the new branches. This would allow service from Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx to have direct service to both 8th and 6th Aves. All remaining funds were shifted to finishing 6th Ave.

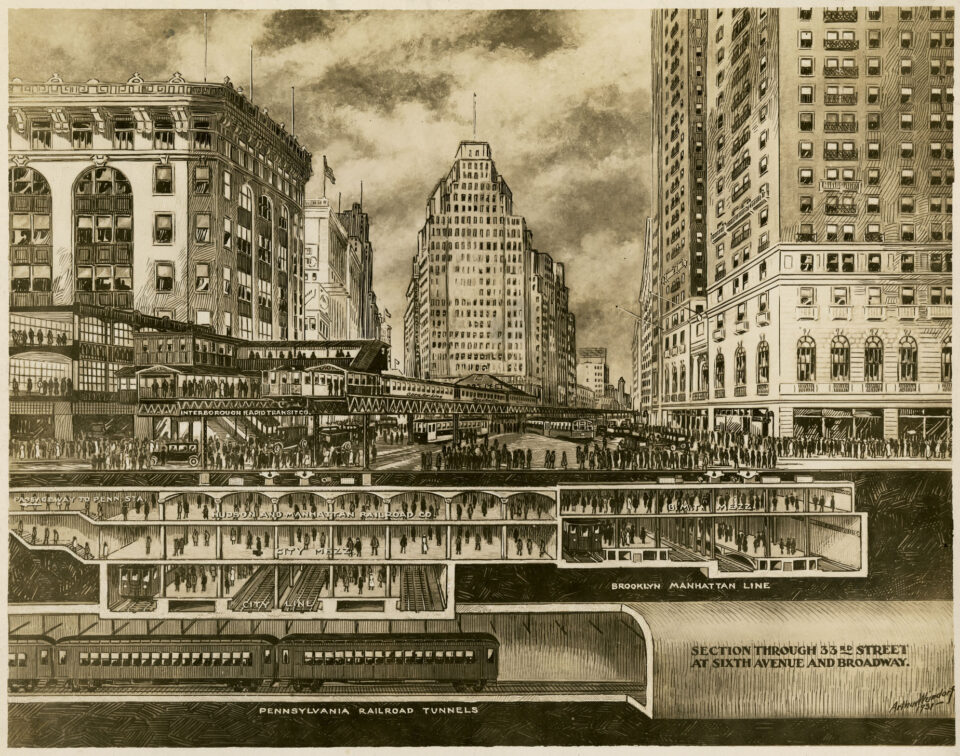

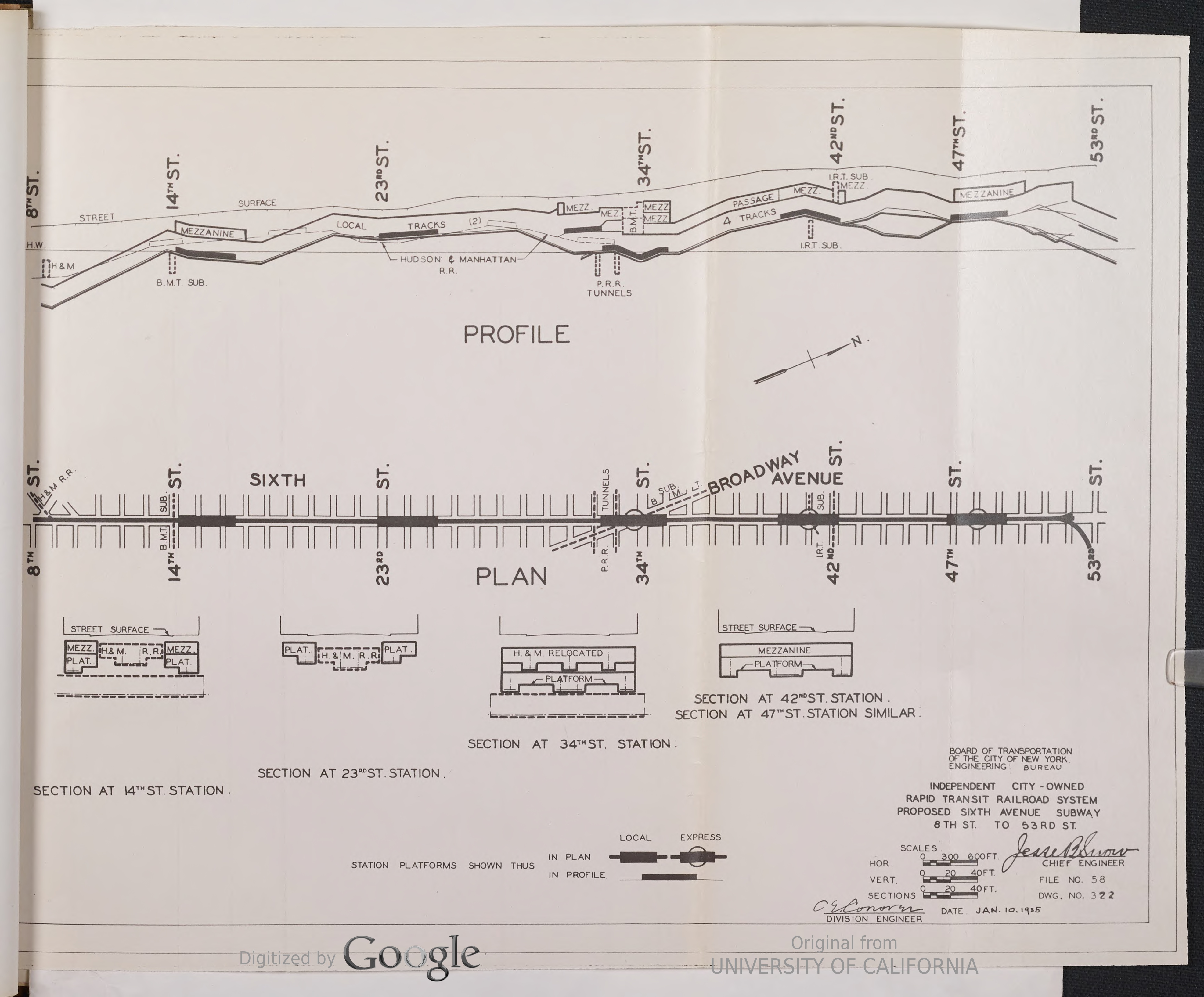

The 6th Ave Line proved to be the most challenging and costly of the entire system. 6th Ave hosted an elevated train that was vital to the Midtown central business district. The city had wanted to remove it priot to construction, but push back from local merchants and businesses forced them to build the subway under the street while supporting the elevated tracks above it (which had also be done for the building of the Fulton St Line in Brooklyn). At 33rd St, the IND had to snake the tunnel between the BMT 34th St station, the 33rd St terminal of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (H&M, today PATH), and the Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels.

Between 9th St and 33rd St, the H&M had built their New Jersey subway down the center of the avenue. Major department stores lined the avenue between 14th St and 34th St, and it would be far too expensive to buy out the landowners to expand build the new subway under private property (as they had successfully done further south in Greenwich Village and the Lower East Side.) The IND considered buying the H&M, but the H&M wasn’t interested in selling.

Facing high construction costs, the IND opted to punt. The 6th Ave Line would be built with 4-tracks between 53rd St and 34th St, 2-tracks between 34th St and 9th St, and 4-tracks between 9th St and 2nd Ave-East Houston St. The center tracks would be designed to angle down where they deadened so that a future tunnel could be built below the H&M. Express tracks would be used for trains to terminate rather than for throug service; B trains would termiante at 34th St, and E trains would terminate at Broadway-Lafayette St.

The 6th Ave Line opened in December 1940, and the IND was declared “finished”. This came with some huge caveats: the Fulton St Line had only opened as far as Rockaway Ave; Work at the East New York (now Broadway Junction) station lacked enough supplies to open, and the South Brooklyn Line ended at Church Ave and wasn’t connected to the BMT Culver Line. The city had only that year successfully purchased the bankrupt IRT and BMT, which was required in order for the IND to connect the lines.

It’s one thing to build a subway system. It’s another thing to operate one and keep it financially healthy. The IND was barely able to build its initial system, but the specter of the 5 cent fare would be its downfall. The city had successfully unified the three subways, but the private companies had long been running in the red, as post-War (World War I) inflation had decimated their profits. To compensate, both railroads had deferred maintenance for decades. By the time the city was able to buy them, the quality of their physical plant was far worse than what had been publicly known. The city now had to begin shoring up two failing subways right as it began paying back banks for the third system it had just built.

Then, all hell broke loose.

The United States entered World War II at the end of 1941. The call to war meant that many of the things that are needed to run and maintain a railroad (metal, oil, men) were soon to be consumed entirely by the war effort. Work on new lines ceased (at this time, the only line remaining unfinished was the extension of Fulton St Line to Euclid Ave.) Maintenance on existing lines was cut back even more. Ironically, because of oil rationing, ridership skyrocketed as commuters ditched their cars in for the train.

When the war ended in 1945, it wasn’t just Europe that was broke and in ruin. The subways were in worse shape than ever, and now with oil rationing ending, people began flocking back to their cars. And they never stopped.

Moses

The city had used building the IND as a way to create new highways through the city. Not only Queens Blvd expanded, but so to were Houston St (East and West), 6th Ave, Church St, and Essex St widened as part of the subway building. The holistic approach to transportation facility expansion changed after World War II, when Robert Moses was able to take control of public works.

In 1933, Moses had begun work on his first parkway within New York City, the Grand Central Parkway, which was designed to connect Nassau County through northern Queens and into Manhattan via the new Triborough Bridge. The Grand Central Parkway was an overnight success as it was the first limited access highway within the city. Trucks were banned, and the road was designed with park-like features for a more pleasurable experience. The road was designed to run along much of the glacial moraine that runs the length of Long Island. In eastern Queens, this means that it swung down through Briarwood, Jamaica Hills and Estates, and Holliswood; The very neighborhoods that had been calling for better subway service before the War. Their more affluent development meant that residents were more disposed to driving rather than taking mass transit.

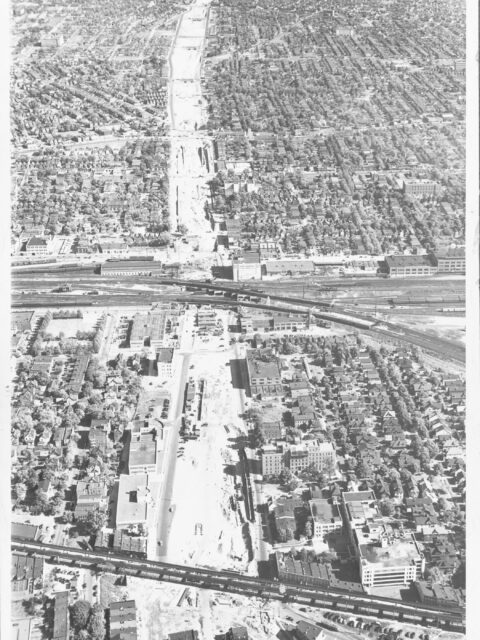

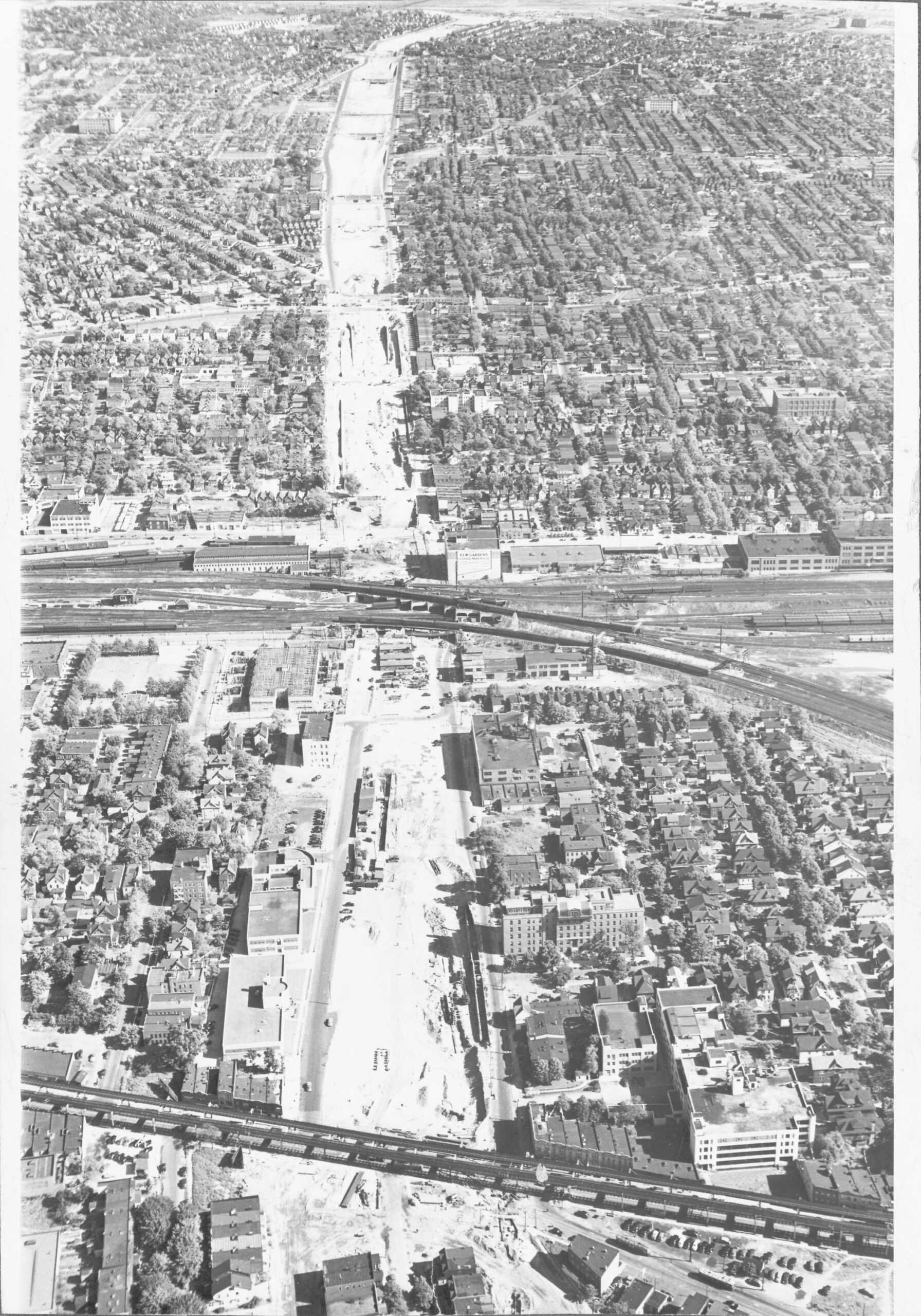

By taking over public works, and funneling traffic through his toll bridges, Robert Moses had the power and the money to dictate what got built. He had wanted to take over Idelwild Airport, which began construction in 1943, but had been usurped by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Still, Moses understood the economic potential for the airport and as soon as the war ended, he began building a new expressway from Queens Blvd and the Grand Central Parkway to the airport. His chosen route was along Van Wyck Blvd.

In 1946, the city began to relocate residents along Van Wyck Blvd and demolish their homes. The small neighborhood of Dunton was literally decimated. Some homes were put on trailers and moved to nearby vacant sites, and one four-story apartment building was lifted and moved. Ultimately, some 263 households were relocated, and the city demolished 355 houses.

Before the War, planners had been developing plans for integrating new highways with transit lines along their center medians. This had been done with streetcars, including along Queens Blvd. But the new highways would be wider and busier, and the transit would be heavy rail. Building new rail lines was becoming prohibitively expensive due to land and material costs. If cities were building new arterial highways by clearing land, it made sense to include space for transit. Chicago built their major interstates with center medians for transit; the Red Line was built along the Dan Ryan Expressway, the Blue Line was built along the medians of both the Eisenhower (formerly Congress) and Kennedy Expressways, and the Stevenson Expressway contains an unused median space.

Robert Moses did not like transit. He saw it as low class, a vestige of an ancient era that wasn’t needed in a world where everyone could drive; Drive on his roads, over his bridges, and pay tolls only to him. When city planners saw that Moses was clearing a path for his Van Wyck Expressway, they suggested that, like the roads before him, transit could be built along the road as well. If not now, perhaps space could be left for when funds were available. Moses refused, claiming that it would cost hundreds of millions more and require demolishing even more homes.

While this argument is technically true, Moses was never one to shy away from kicking people out of their homes. It’s also disingenuous, given that the southern section of the expressway features a large landscaped embankment that’s more than wide enough for a transit line. Had the Van Wyck Expressway been built by someone other than Robert Moses, the provisions for the Van Wyck Line could have been linked up with the median of the road, and South Richmond Hill, South Jamaica, and South Ozone Park residents would have direct express subway service. Like the Blue Line in Chicago, the E train could have extended directly to the terminals of JFK Airport.

Back in 1941, coming home from a civic meeting in Richmond Hill, Joseph Coyle contracted an unknown illness. The next day he died at age 49. The dream of the Van Wyck Line died with him, to be buried for good beneath the roads of Robert Moses.

178th, or 179th?

Supporters of at station at 178th St were luckier, although not because of their advocacy. The Queens Blvd Line had been a victim of its own success. Similar to the Astoria and Flushing Lines, improved transit brought massive development. Queens Blvd developed less like the art deco apartment-lined Grand Concourse than originally envisioned, but drove the development of garden apartments in new neighborhoods such as Rego Park and Forest Hills.

The choice to route all express trains to Manhattan and all local trains to Brooklyn proved to be a poor one. While downtown Brooklyn and the Navy Yard may have been large centers of employment before the War, after the War many firms packed up for Midtown, and the Navy Yard wasn’t needed. Heavy manufacturing, once the dominant industry in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, began moving out to more modern facilities, outside the city, and often outside the state. Fewer people needed to take the Crosstown Line into Brooklyn, while ridership on express trains to Midtown were at crush levels.

There was obviously a need for more service into Manhattan. The express tracks were at capacity, so a connection to the local tracks were the only option. This was noted as far back as the mid 1930s, when a second IND tunnel was proposed between the Upper East Side and Astoria. The 6th Ave Line would be extended north, under Central Park, turning east under 76th St, crossing under the East River and Roosevelt Island to Broadway in Astoria. From here, the line would continue southeast until Steinway St, where it would take over the local tracks from the existing Queens Blvd Line. The existing Steinway St station would have been converted into a terminal for Crosstown Line trains. None of this came about, although the city eventually revisited the idea when it built the 63rd St Tunnel.

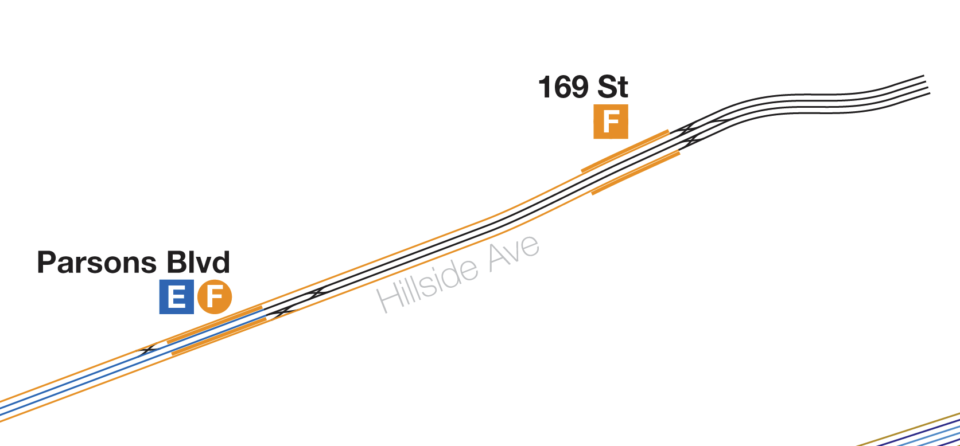

That added capacity also needed somewhere to go on the opposite end of the line. Because 169th St station was never really intended to be a terminal, the switch configuration greatly limited throughput. Express E trains would terminate at Parsons Blvd, one station prior, while the local F trains would terminate at 169th St. The tracks east to 178th St were used for turning and storage, but the inefficient layout reduced capacity.

In 1947 the city embarked to finally fix the problem and construct a proper terminal. The new station would be built immediately to the east of where the tunnel walls ended. Past the station, a two level, 8-track storage yard would allow for added capacity and flexibility. The station opened in 1950 and boasted 12 entrance stairways for better egress. One test of service showed that the terminal could handle a throughput of one train every 57 seconds, or 63 trains per hour. It would never come close to that level of service since. The station would be a major hub for Long Island bus routes and is still to this day has the highest ridership of all the Hillside Ave stations.

Oddly, the station which had always been proposed as 178th St ended up being called 179th St. The station’s location to the east of 178th St probably had something to do with it. 179th St was the very last subway line that the city ever built itself (the Fulton St Extension had opened in 1948.) Deeply in dept, and with all infrastructure investment shifting towards highways, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) was chartered in 1953 to take over subway and bus lines. Public Authorities were seen as independent of city and state politics. This was important when it came to raising the fare, which had always been political suicide. The city had finally raised the fare to 10 cents in 1948, and the NYCTA raised it to 15 cents in 1953.

Public authorieis could also float their own bonds to raise money. With newly issued bonds, the NYCTA set about fixing up the aging system. They were finally able to connect the IND South Brooklyn Line to the BMT Culver Line, completing the dream of the early IND of having their own subway to Coney Island (and, more importantly, reducing the bottleneck along the 4th Ave Line at DeKalb Ave.

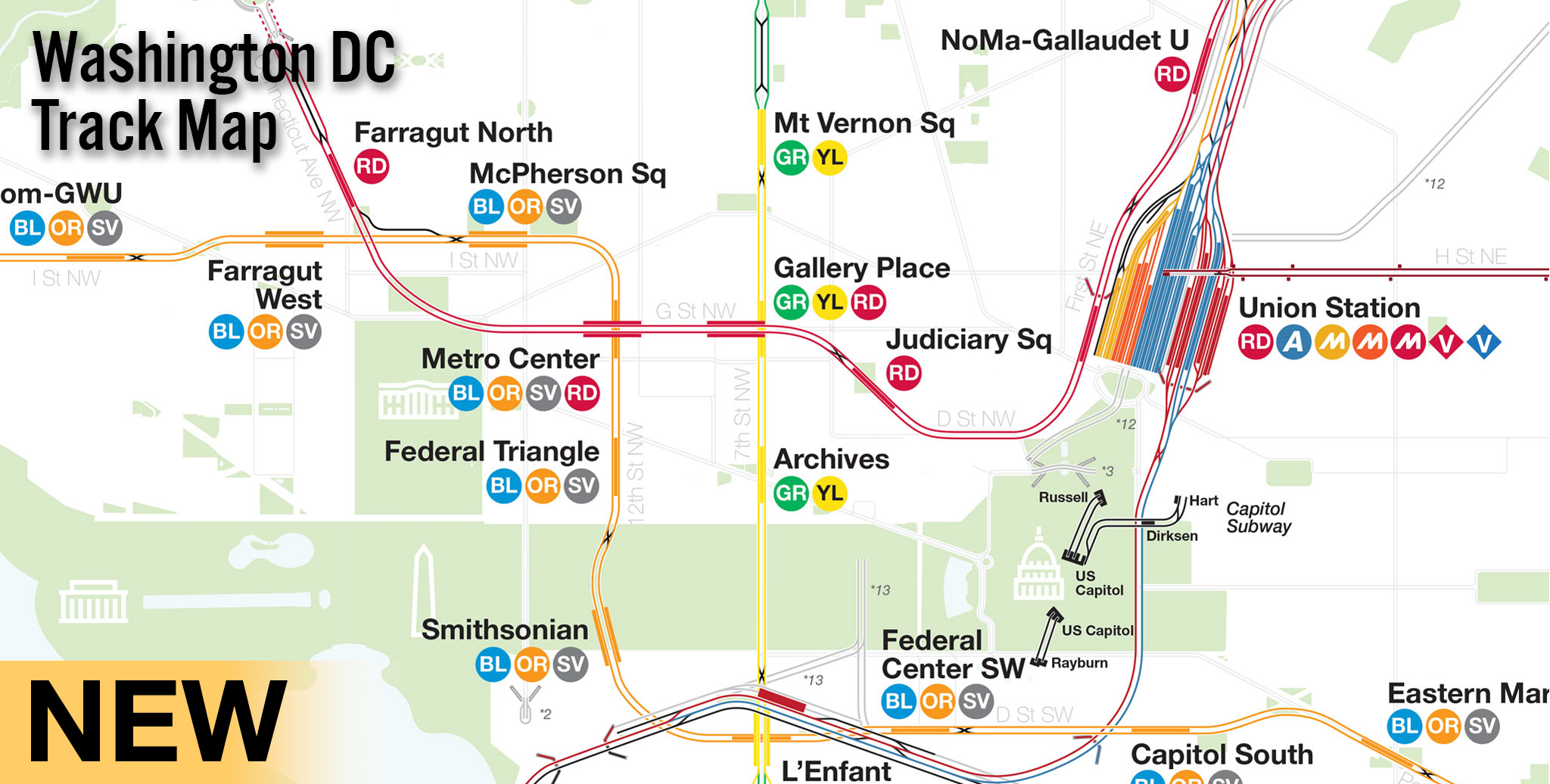

In 1955, they opened the 11th St Connection, 2-track tunnel connecting the BMT 60th St Tunnel between Midtown and Long Island City (which also serves the Astoria Line) with IND Queens Blvd Line at Queens Plaza. For the first time, Queens Blvd Line riders could have a one-seat-ride to Manhattan via the local tracks. Soon, this too was not enough.

The limited local service hadn’t proved sufficient for the levels of ridership. Riders still preferred the express trains, even when in certain instances they didn’t save all that much time. Riders at Roosevelt Ave, the first express stop past Queens Plaza, would crowd into express trains so much that trains would be delayed in the station. The massive new terminal at 179th St would never see anywhere near the 63 trains per hour that it was designed to handle because local riders east of 71st Ave-Continental Ave balked at having to transfer to the expresses when before the expresses would directly serve them.

Even if the city had been interested in extending the Hillside Ave Line further east, the ridership imbalance would have proved too problematic. Extending the express trains deeper into Queens just meant more packed trains in western Queens. When building the 179th St station, provisions were left in the walls at the end of the layup tracks so that a 2-track extension to Springfield Blvd, as envisioned by the IND Second System, could one day be built.

It is very unlikely that this will ever happen. Eastern Queens, in part due to the lack of subway lines, developed around the car and the highway. Hillside Ave, being at the base of the glacial moraine and with a high water table, has the unfortunate reputation for being heavily flood prone. In strong storms, rain washes down the hill directly into the subway. Even when the water disperses, the high water table means that it infiltrates the tunnels more than in other places. This means that, even if the MTA wanted to extend the subway, it might only make sense to build it elevated.

Proposing a new elevated line in New York in this day and age may very well be a non-starter. The only place it’s been pulled off, ironically, was along the Van Wyck Expressway. Finally, defying Robert Moses, in 2000 the Port Authority (one of the very few bodies that could ever successfully oppose him) opened the JFK AirTrain between the LIRR Jamaica station and the JFK Airport terminals. This light rail line was built along the median of the Van Wyck Expressway. With no space at ground level, the AirTrain is built on a concrete viaduct above the road. Residents at the time were wary of the system, but since it was running above the deafening roar of over 100,000 vehicles, the quality of life argument was harder to make.

John Delaney retired from the Board of Transportation in 1945. Delaney was not just a great builder of public works, he was a great salesman too. Delaney knew that in order to keep funds coming in for his lines, he would need to keep public support going. To do this, he used his planning powers to propose lines that he knew may never be built. The Van Wyck and Hillside Ave Lines were needed for continued support by Queens politicians in Albany. He sold the city a dream that we are still captivated by today. In another bit of irony, the Queens Blvd express tracks finally made it to Sutphin Blvd as part of the Archer Ave Subway.

Such a great piece with amazing history! (Need to read your blog more.) It is a shame though we don’t have a real subway line to JFK, especially given the way the Port Authority runs the AirTrain.

One minor knit: the AirTrain opened in 2003, not 2000. I remember because I rode the old shuttle bus from the A exactly once before the AirTrain opened the year I moved to New York.

Where did you find the “Profile of the IND 6th Ave Subway” diagram? I was looking for information about the depths of the tunnels in the NYT Museum Archive but they don’t have any high-quality scans. I searched for the “University of California” scans shown in the image but couldn’t find anything either.

I think this is something I found on Twitter. A lot of the info on the building of the IND isn’t digitized fully, or if it is, it’s behind a university pay wall.