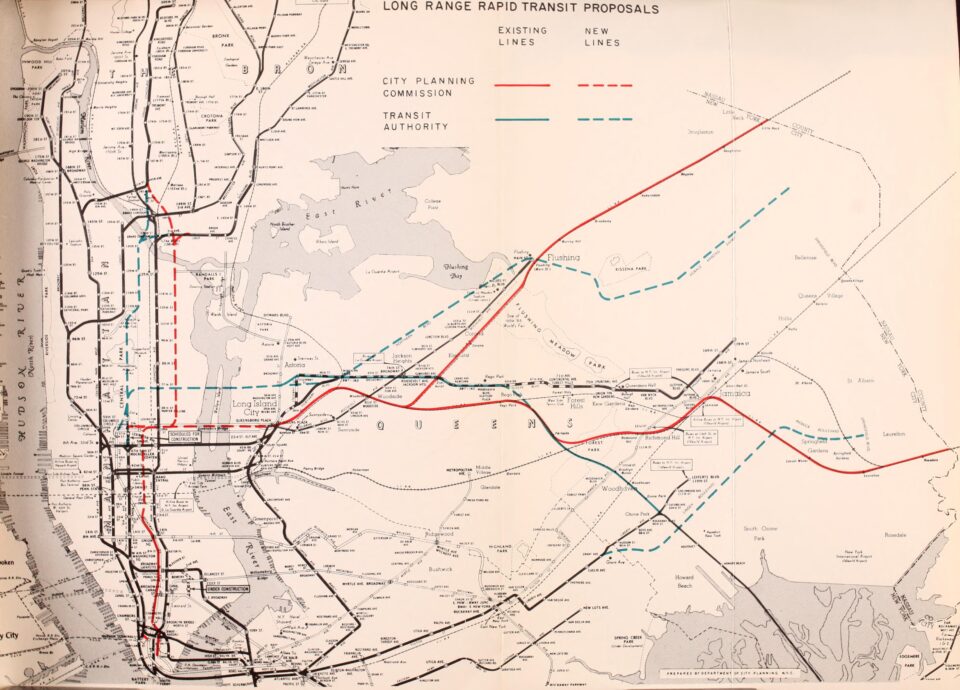

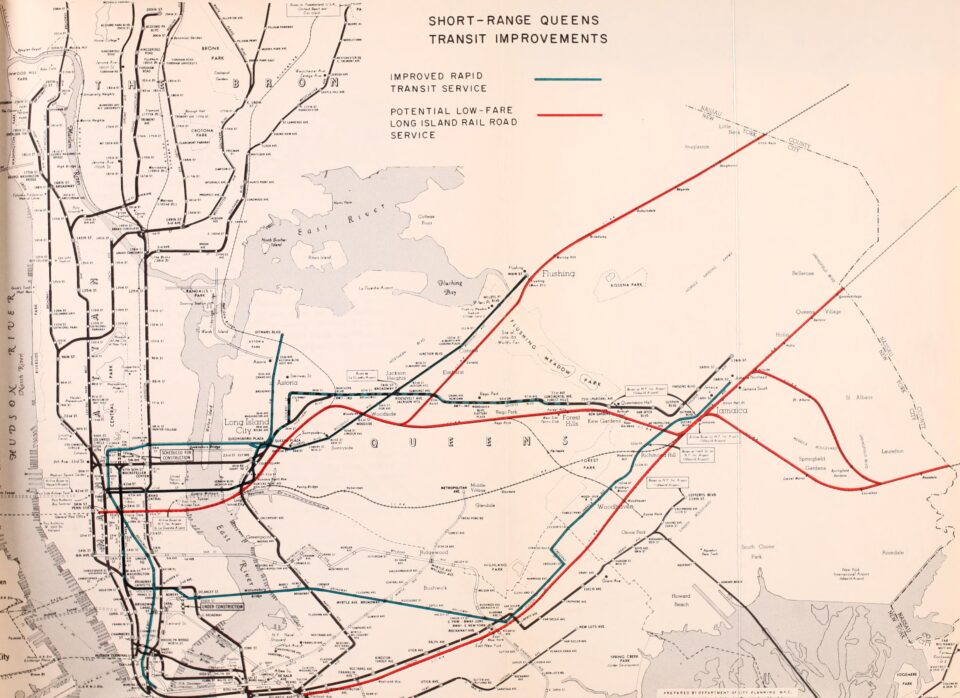

In part one of this series I looked at the long, tortuous history of Route 131 and how we ended up with only a few short miles of new subways in Queens. In this post I will go through the official report outlining the Southeast Queens Line and discuss if built it today makes sense.

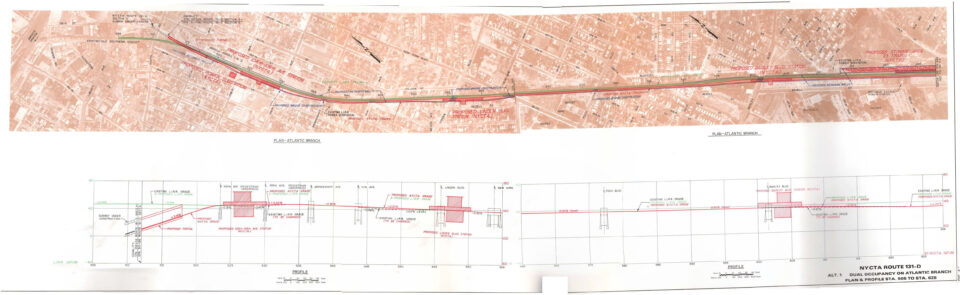

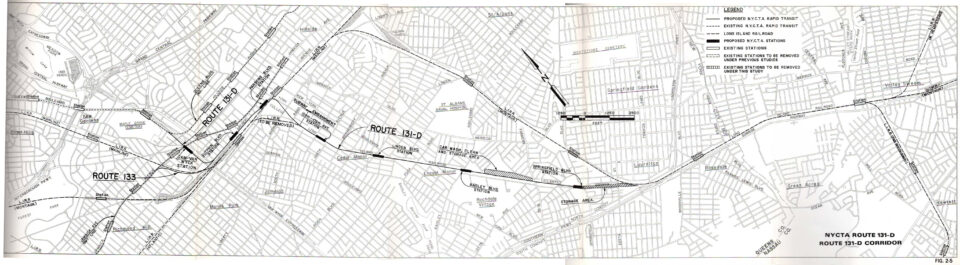

In 1974, the MTA asked a private engineering firm to draft a report looking at two possible alternatives for building Route 131-D, also known as the Southeast Line (SEL). In 1978, they gave their report to the MTA, which looked at two alternatives: the first was keeping the LIRR Atlantic and Montauk branches (through southeast Jamaica) as is and extending the Archer Ave Line alongside of the Atlantic Branch, the other was to completely convert the Atlantic Branch to subway service and expand the Montauk Branch to three tracks.

The report found that the first alternative would require the acquisition of 241 properties along the right-of-way (ROW) and cost $147.8 million ($671.62 million in 2022 dollars) and the second alternative would require taking only 22 properties and cost $134.6 million ($611.64 million in 2022 dollars). Note, these costs would NOT include the real estate acquisition costs. The report also noted that the second alternative would provide better (i.e. cheaper) operations for both the subway and LIRR.

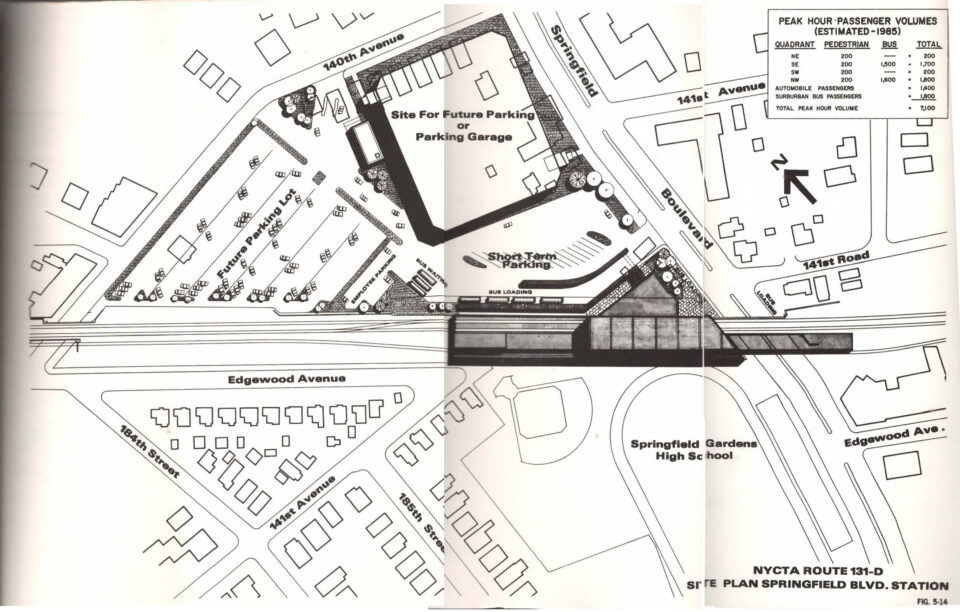

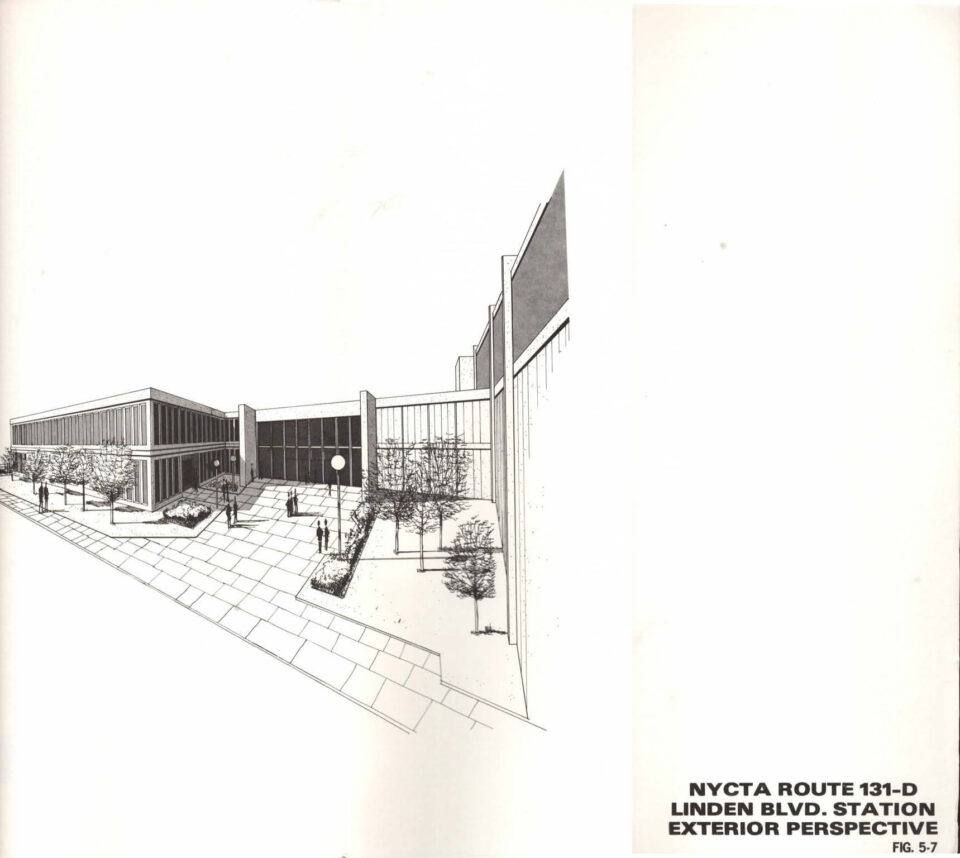

Stations were proposed at 108-109th Aves, Linden Blvd, Baisley Blvd, and Springfield Blvd. The LIRR stations at St. Albans, Springfield Gardens, Locust Manor, Laurelton and Rosedale would all be closed. (Since the SEL was never built, only the Springfield Gardens station was abandoned; the report noted that it only saw 8 daily riders.) A maintenance facility was to be built on the north side of the tracks between Baisley and Farmers Blvds, adjacent to what is today Gwen Ifill Park. A storage yard holding 20 trains was planned to be built along the ROW after the Springfield Blvd station.

The report proposed that the extension would have almost 15,000 daily riders (about 5 million annual riders) by 1985. Bus ridership (2019 numbers) suggests that this number would be similar, if not higher today: routes Q111, Q113, and Q114 (along Guy Brewer Blvd) saw 6.2 million annual riders, while route Q5 along Merrick Blvd saw 3.3 million annual riders.

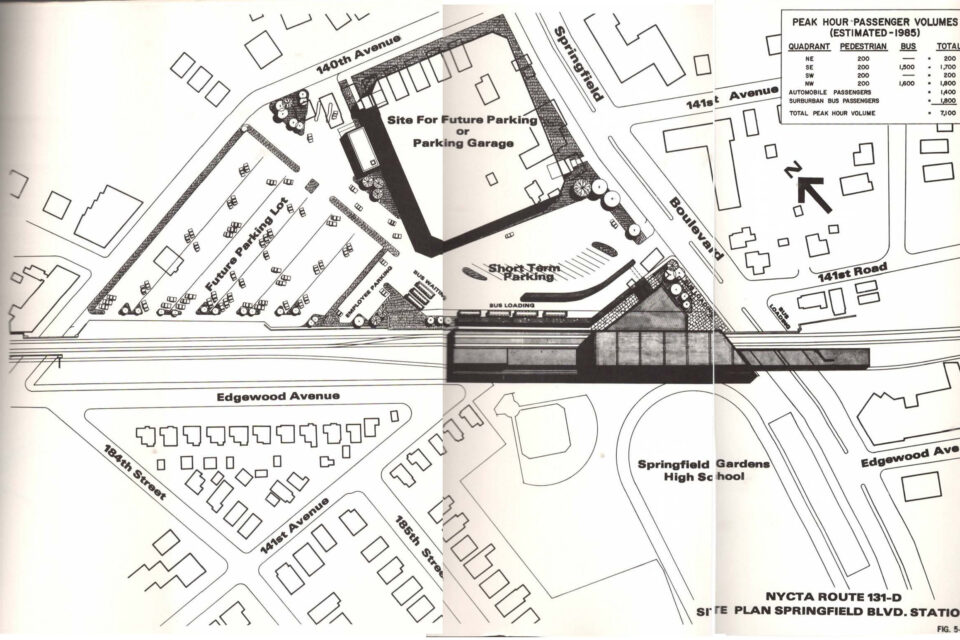

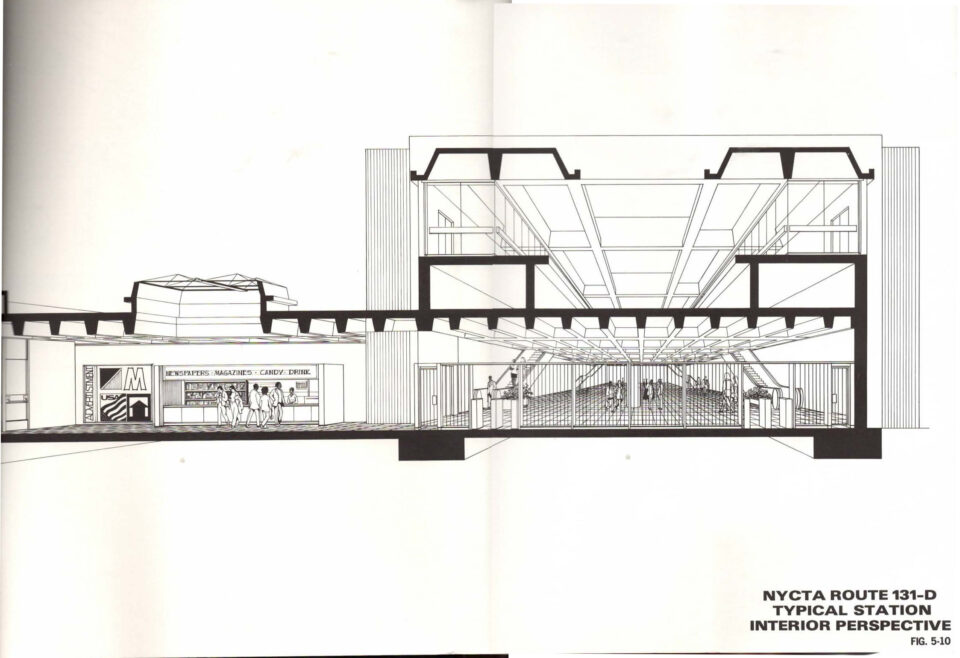

The report is very much a product of its time. Transit planning in the 1970s was heavily focused on getting drivers from the suburbs onto trains. This requires parking. While the first alternative looked at required taking a high number of properties in order to expand the ROW, the second alternative still required property takings due to planners wanting to have large stations that could handle more parking and bus drop-off zones.

This report was not an entire Environmental Impact Statement. It did not consider alternatives such as Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) or improved LIRR service. It’s unclear if such a proper study was ever completed, though given the track record of the Program for Action, it didn’t really matter since the SEL was most likely going to be cut by the time this report was submitted to the MTA.

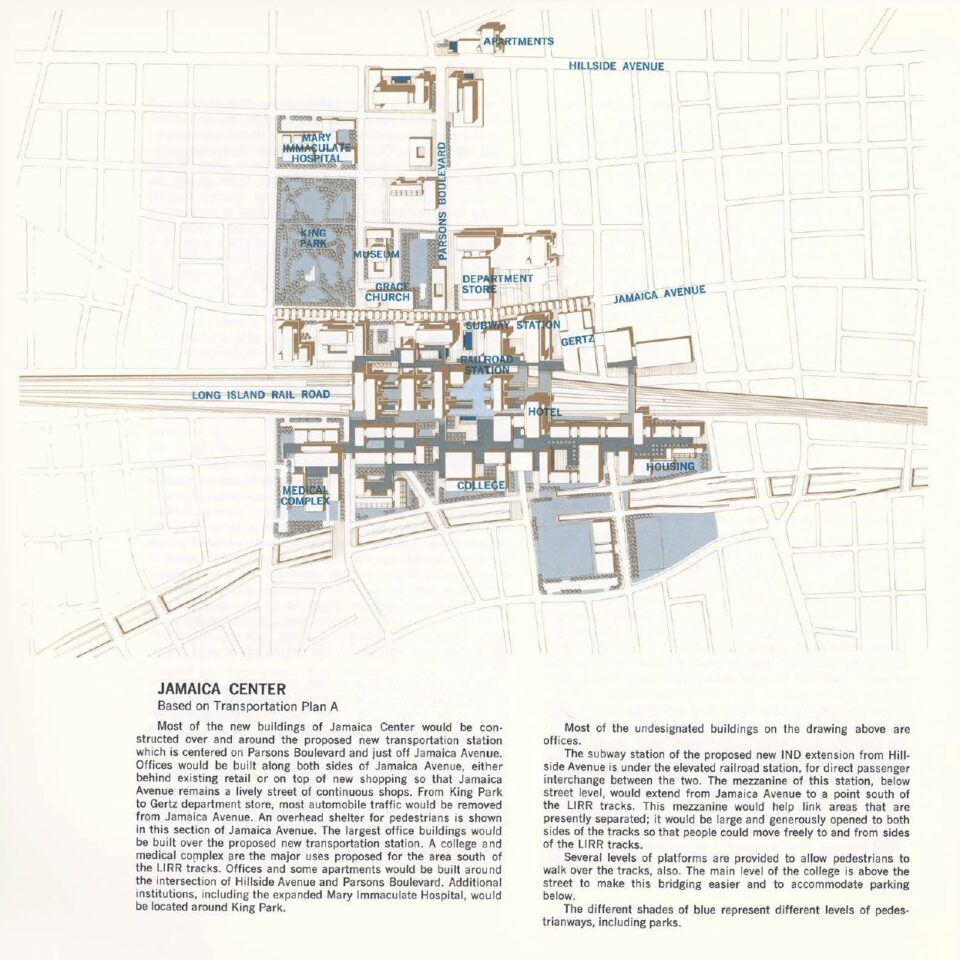

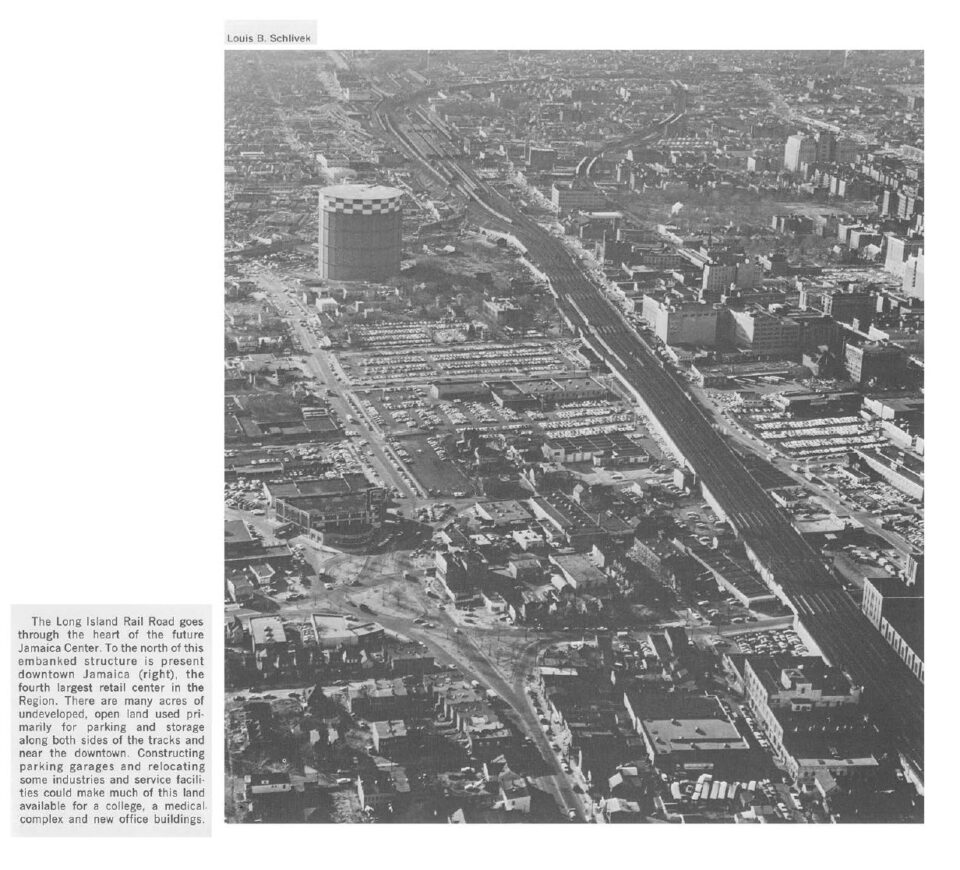

The SEL was intended to support urban renewal projects in Jamaica, such as new housing projects and the York College campus. A 1968 report by the RPA has some interesting ideas for how central Jamaica could have been redeveloped, including moving the main Jamaica Center station to the east, the Archer Ave Lines, and a new sunken expressway along Liberty Ave. The planned development over the LIRR Main Line has all the hallmarks of late-60s futurist planning.

Much of the planned redevelopment stalled due to loss of funds, but today downtown Jamaica is a hotbed of activity with giant towers going up around the LIRR station. While development in Jamaica has certainly happened despite the lack of the SEL, it’s safe to say that more and denser development would have been built had the SEL been built.

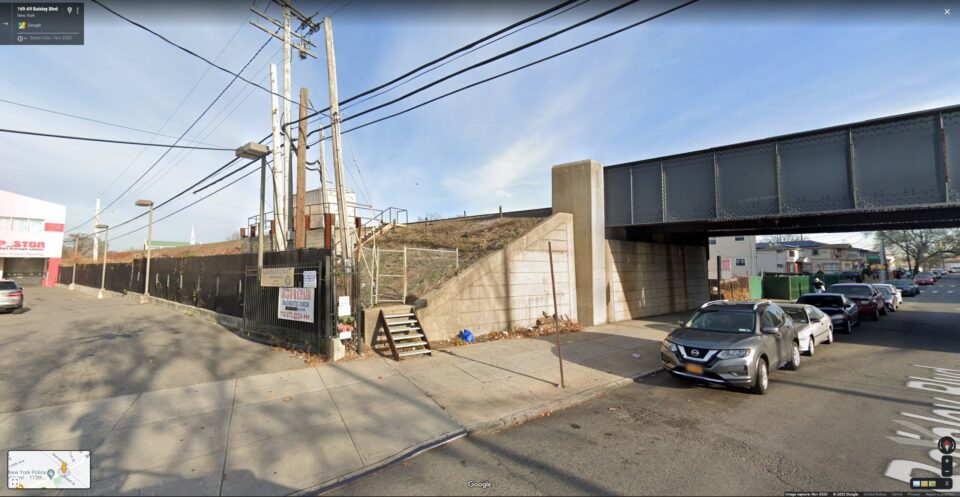

The ROW of the LIRR Atlantic and Montauk Branches are largely the same today as they were 44 years ago. Both are entirely grade separated with bridges over major cross streets. The embankments are mostly trapezoid shaped, meaning that the base is wider than the top, where the rails are. Expanding the top of the embankment to allow more tracks is entirely feasible for both lines, but the ROW for the Atlantic Branch is more constrained in places, hence the requirement for taking more homes. The Montauk Branch has less constraint, though the newly expanded rail beds would require retaining walls to be built along the backside of private property.

Service

The Atlantic Branch serves the Far Rockaway and Long Beach Lines, while the Montauk Branch serves the Babylon and West Hempstead Lines. Service and ridership on these lines are far from equal: the Far Rockaway Line saw 7tph peak AM service, 4tph reverse peak (2019), and the Long Beach Line saw 5tph peak AM service, 2 reverse peak (2019); the West Hempstead Line saw 2tph peak AM service, 1tph reverse peak (2019) and the Babylon Line saw 16tph peak AM service, 2tph reverse peak (2019).

At first glance, it may seem strange to take 4-tracks of the LIRR and shrink them to one, but the imbalance in service, combined with the land use of the south shore of Long Island, suggests that this might be a worthwhile right-sizing.

Taken as a whole, the south shore of Long Island is far more residential than the center of the island. The Montauk and Atlantic Branches serve mostly bedroom communities and small towns rather than the commercial and industrial centers in central Nassau County. This means that the reverse peak potential is far less here than along the Main Line. Therefore, peak train service will always be more important than reverse peak here. Having both the Atlantic and Montauk Branches, with 4-tracks total, is more track capacity than is needed.

Alternative 2 for the SEL proposed expanding the Montauk Branch from 2 to 3-tracks. 3-tracks would easily provide +45tph in peak direction with space for more peak and reverse peak service than is run today. The 2-tracks of the Atlantic Branch would also see far more service as an extension of the NYCT E train than they could as LIRR: E trains today run at 15tph both ways at peak, but are limited along Archer Ave to 12tph; with an extension of the SEL, added layup tracks, and taking advantage of the new CBTC signals, the E could see up to 18-20tph.

At the time, planners didn’t think the SEL could work without the added capacity of the Super-express Bypass from LIC to Forest Hills. But advances in signal technology, known as Communication Based Train Control (CBTC) means that more trains can be fit along the existing tracks. CBTC has the potential to add enough extra service along the Queens Blvd Line to make up for the lack of the Super-express Line (although, it can’t speed up service all that much as trains will still make the same number of stops.)

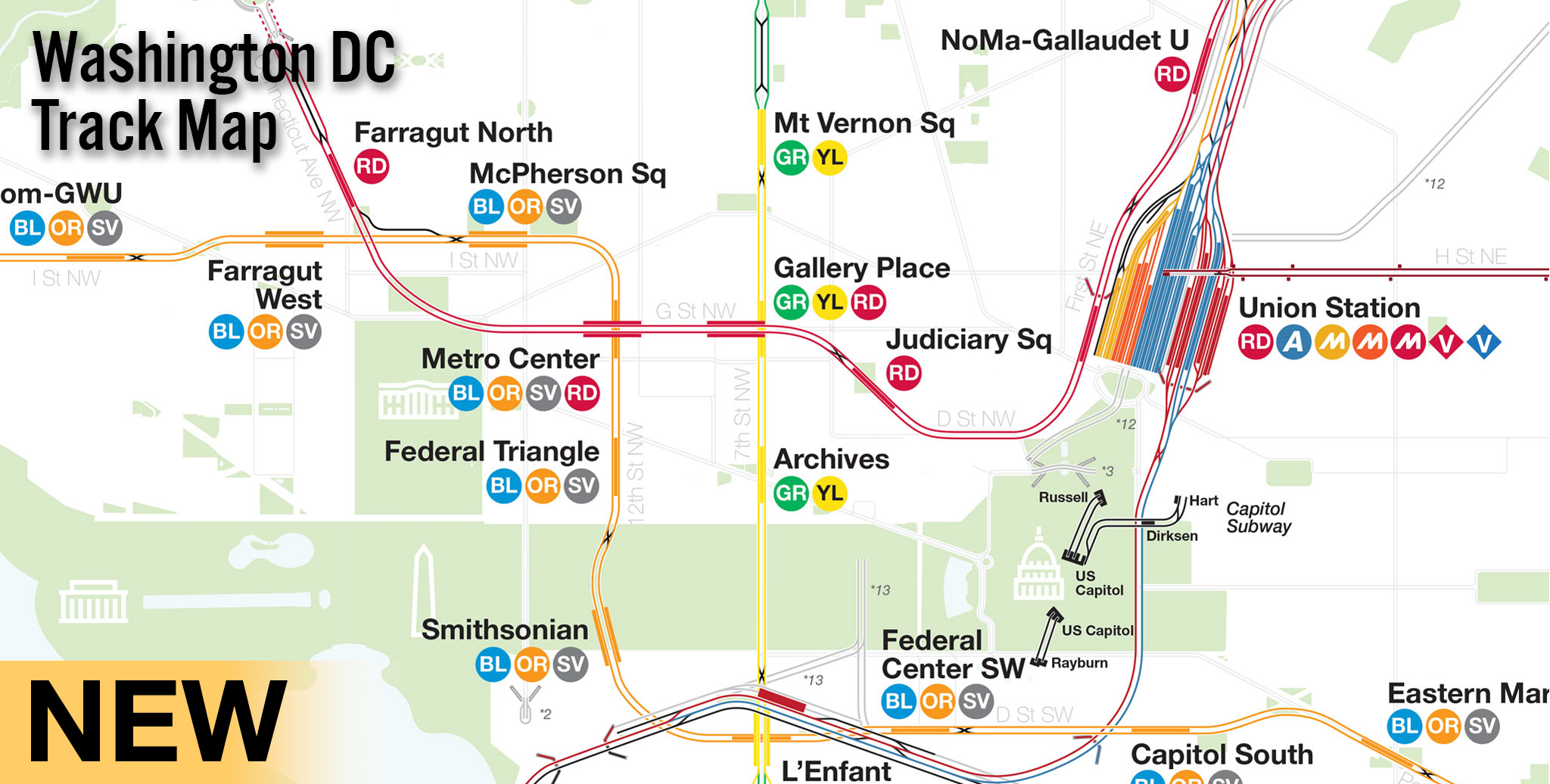

The MTA was excited to convert the Queens Blvd Line to CBTC to allow for more trains, but bottlenecks throughout the rest of the system will handicap these improvements. As mentioned, the Archer Ave Line is limited due to the fact that it was never designed to act as a terminal; poor switch location in the tunnel limit how many trains can turn around at Parsons/Archer Ave station. Additional express trains are run out of 179th St instead.

Stations

The planned station designs were going to be a marked departure from traditional NYCT stations. The report goes into great detail about how, due to the suburban nature of southern Jamaica, drivers and drop-offs were going to bring a large percentage of riders. One of the reasons for the high number of homes to be taken was to facilitate larger station profiles that would include bus loading zones, parking, and drop-off locations (“kiss-and-ride” as it was known at the time.)

Because of the financial crisis of NYC in the 1970s and the overall lack of investment in the transit system at that time, the NYC subway does not have many examples of modernist architecture. The stations along Archer Ave and the 63rd St Line are the only examples of large, modern (some would say Brutalist) architecture which was prevalent in new transit lines at the time. The stations of the SEL would have fit very much into this design ethos.

One of the most important features of the SEL was the proposed storage and maintenance facility to be built near the end of the line. This would have added space for up to 36 trains, enough to serve the entire line. The storage would be split between an area between the tracks and Gwen Ifill Park, and an area contained by the ROW between Springfield Blvd and North Conduit Ave. The roughly 5 acres next to Gwen Ifill Park is still zoned for transportation to this day.

Part of why the first alternative was so much more expensive than the second was that access to this area from the new NYCT tracks parallel to the LIRR would require an expensive fly-under track. By converting the Atlantic Branch to NYCT service, a simple switch could be installed. This would also simplify operations; the fly-under track would require trains to double-back at Springfield Blvd, clogging up service.

Does the SEL make sense today?

The SEL corridor today is an obvious choice for transit investment, but just what kind of investment is needed depends on current and future factors. The SEL was born when the NYC subway and LIRR, not to mention local buses, were all controlled by different agencies. When these were eventually brought under the umbrella of the MTA, many hoped that these services could be better integrated. We are still waiting for this today. So potential SEL plans have to be flexible.

South Jamaica is typical of the more suburban areas of NYC: single or multi-family homes with small sections of denser apartment buildings, commercial strips of single story buildings, and areas of light industry (mostly automobile related.) The most interesting area that stands out is the Rochdale Village development, a massive middle-class co-op home to more than 5,800 apartments. This development, while dense and served by the LIRR Laurelton station, is typical of post-war housing in that it is centered around car dependency.

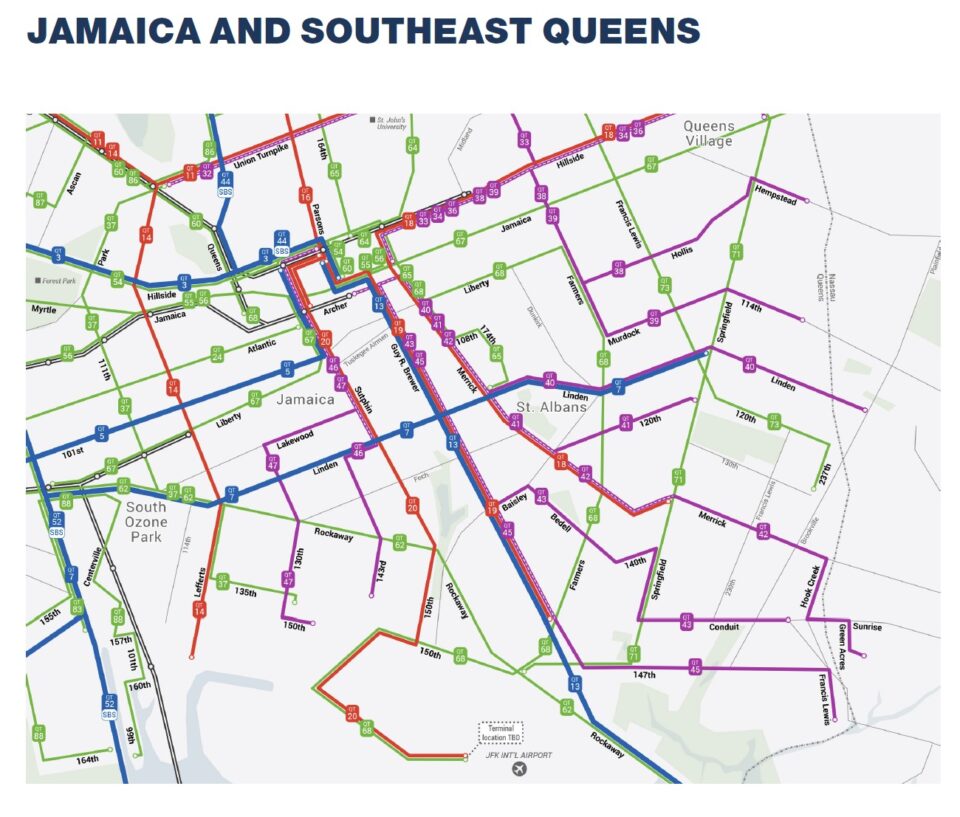

South Jamaica is served by the LIRR Atlantic Branch and a number of bus lines. These bus lines are primarily laid out in the typical radial-fan design, focused on central Jamaica. The Queens bus network redesign is planning on changing this to have more “crosstown” service into Brooklyn, but will also strengthen many of the radial routes with express and local service. There is also a strong network of jitney buses, so-called “Dollar Vans” which offer low-cost alternatives to poor bus service.

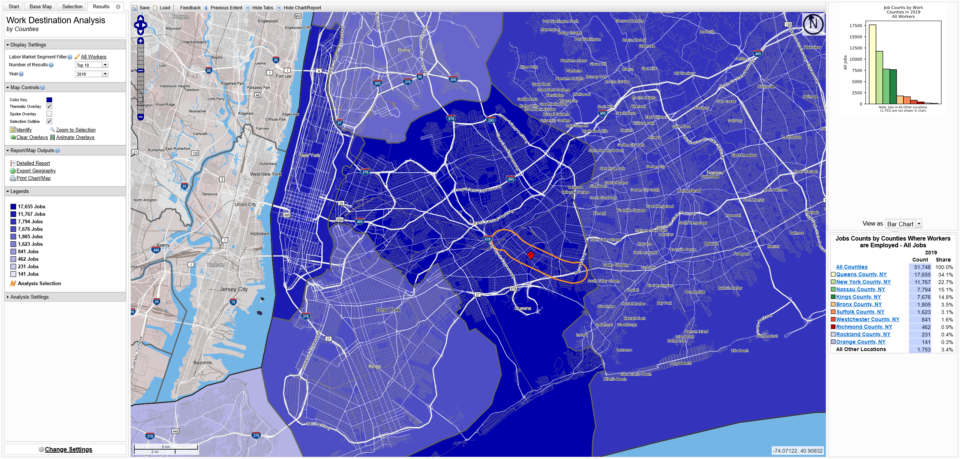

There were, in 2019, just over 51,000 commuters living within a half-mile of the Atlantic Branch. 34% of these worked within Queens, 22.7% worked in Manhattan, 15% worked in Nassau Co., and 14.8% worked in Brooklyn. Given the existing road and rail infrastructure (South Jamaica is surrounded on three sides by expressways and parkways), this breakdown makes obvious sense. It also makes potential rail-based solutions more complicated.

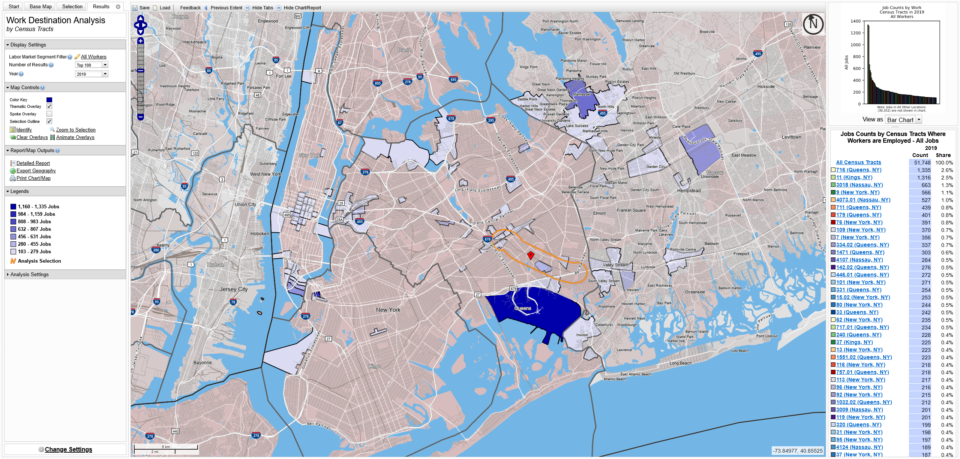

Looking at a breakdown of job locations based on census tract, the largest employment center for workers along the line is JFK Airport. Past one-seat-ride rail connections to JFK looked at various ways to branch off of the LIRR Atlantic Branch and enter the airport from the northeast. This would have required building an elevated track through Baisley Pond Park, which was seen as a non-starter. Eventually, the Port Authority built the AirTrain along the Van Wyck Expressway. In a sense, this serves commuters to the airport well, but in reality, workers would need to not only travel all the way to Jamaica Center and double back, but also pay a second fare. More likely, workers drive or take local buses.

Two notable job centers are in Manhasset-Lake Success and the Roosevelt Field area of Hempstead. These areas, while served by the LIRR, are more likely accessible by car via the Cross Island Parkway and Long Island Expressway. Reverse commuting is possible, but poor LIRR service would make the trips very long; for instance, a commuter leaving Laurelton at 6:01am would get to Woodside at 6:29am, wait 13 min for a Port Washington train, and get to Manhasset at 7:07. NICE bus service is an alternative, but making the same trip would require waiting 20 min in Jamaica to transfer and getting to Great Neck station at 7:32am.

There are a number of clusters on the south shore, notably around Valley Stream. While these do show up on the map, the hard numbers tell a less interesting story: only about 970 workers are reverse commuting. That is less than one full train worth of people. This leaves the rest of the jobs scattered in the usual places: Midtown and Lower Manhattan, Long Island City, downtown Jamaica, and downtown Brooklyn.

Looking closer, we see that even Lower Manhattan and downtown Brooklyn have a small share of commuters. This is interesting given that most Far Rockaway and Long Beach Line trains terminate at Atlantic Terminal. The LIRR knows this and is planning on rerouting most of these trains to Midtown when East Side Access (e.g. Grand Central Madison) opens.

Chicken and Egg

Transportation infrastructure lays the foundation for how an area will develop. South Jamaica has only ever had the LIRR, a few trolley lines, and the highway to develop around. As such, the land use pattern favors the car. It’s no wonder, then, that so many of the major job centers for these workers are located in places that are nearby or easy to drive to. Improving transit along this corridor won’t be about addressing existing demand, rather it will be about fostering new development and laying the groundwork for new commuting patterns.

Planners in the mid-20th Century were focused on getting drivers out of cars and onto trains. But that is only half of the equation here. In part because more transit wasn’t built in the 1970s, large areas of South Jamaica remain underdeveloped. The land between the LIRR Main Line and Tuskegee Airmen Way on either side of the LIRR Atlantic Branch is woefully utilized. Vast empty fields surround the York College campus, and Liberty Ave is home to a number of industrial sites, some of which have been found to be polluting the ground.

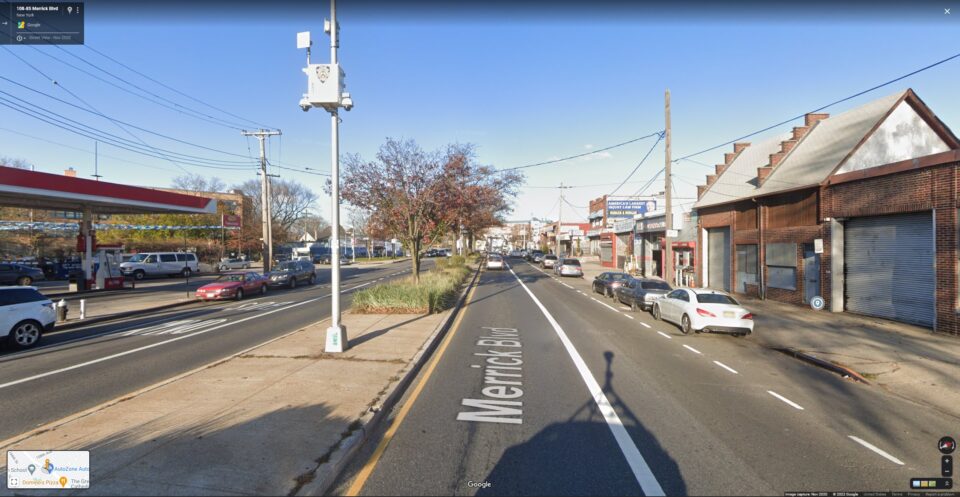

Further out, Merrick Blvd is home to many low-density commercial buildings and large parking lots. Because of its Le Corbusier inspired design, Rochdale Village has a number of large parking lots and suburban shopping centers that could all support housing built above. There is far more potential for affordable housing here than in areas where land prices are higher. Instead of gentrification, development could be far more equitable here with far less displacement.

What type of service?

Because the 1978 study for the MTA about the SEL did not consider alternatives, we must weigh the options. The SEL was a top-down plan: expand the subway. BRT is an option, but given its limitations for increasing development, it’s an option with limited potential. Given that this is an active commuter rail line, the regional rail option must also be considered.

The MTA is currently working on a redesign of the Queens bus network. The redesign plans on simplifying routes, adding new routes, and running different levels of service. The two core corridors in South Jamaica are Sutphin Blvd and Merrick Blvd. The MTA and DOT have already installed bus priority lanes on Merrick Blvd and have seen improved bus speeds. But bus lanes are only as good if they can keep cars out of them. The land use along Merrick Blvd is not only car-dependent, but many of the businesses along the route are car-related and often see cars double-parked in the streets.

The bus network redesign is incredibly important for addressing how riders get around, but it’s only a good first step. The streets of Queens, even wider boulevards, are still very narrow. Bus lanes will have to compete with parking, and in car-dominated are that’s a hard trade-off. This makes an auto-dependent land use policy all the more detrimental. Bus lanes won’t have a real chance unless we take steps to reduce the number of cars on the road in the first place. Land use in the area won’t change for the better unless the rail infrastructure is improved.

Further, many of the bus lines are being redesigned as feeders to existing subways. This shows a strong need for expanding subway service deeper into Queens so that feeder lines can be shorter and overall trips faster. This is something that can’t be done with current LIRR service, though that doesn’t mean that we can’t reimagine that to work better.

Regional Rail vs. Subway

Given that the LIRR Atlantic Branch runs between two proposed bus priority corridors, it only makes sense that more focus should be made on improving rail service. Service on the Far Rockaway and Long Beach Lines are planned to shift entirely over to the Main Line once Grand Central Madison (GCM) is open. No longer will these lines serve Atlantic Terminal, and there will be a 60/40% split between trains to GCM and Penn, respectively. The LIRR, unfortunately, is still running traditional style commuter rail service with a combined 6.5tph on the Far Rockaway and Long Beach Lines at AM peak, and only 3tph reverse peak.

Before the pandemic, the LIRR implemented the Atlantic Ticket on the Atlantic Branch between Atlantic Terminal and South Jamaica stations. It has been popular, as it reduces the $7.50 one way, off-peak price ($10 peak) to just $5. It simplifies travel, though it doesn’t work if you want to go to Penn Station. This will have to be addressed once GCM opens when ALL service will be rerouted to Midtown.

Regional rail advocates want to see the Atlantic Ticket program expanded to all LIRR stations within city limits (and Metro North stations, for that matter.) What is missing in this is the ability to freely transfer to a bus or subway. Without that, riders still face double fares and travel around the LIRR that isn’t expressly going to Midtown will be limited.

From the outside, improving service on the Atlantic Branch seems as simple as implementing this fare reform and adding a few new stops. But the network is limited, so adding more service is not so simple. Adding more service between Midtown and the Atlantic Branch might not be possible given the interlining with almost ever other LIRR service on the Main Line. That means additional service can only be run to Atlantic Terminal. Post-ESA schedules show that the LIRR is only planning on running 5tph at peak between Brooklyn and Jamaica. Most of this service will be relegated to a shuttle, though a select few trains will continue east.

There is no reason the LIRR can’t run more service on the Atlantic Branch between Brooklyn and Jamaica. But even doubling service between Atlantic Terminal and Far Rockaway/Long Beach means that service is limited to about 13tph in peak directions. Reverse peak would need to see a much larger boost, from 3tph to 10tph. This is all technically feasible, though far from ideal.

Adding infill stations adds time. With the addition of three new stations between Jamaica and Locust Manor, the total travel time will be increased by 6 minutes each way. That makes overall travel time from Laurelton to Penn Station go from 28 minutes to 34 minutes. This easily beats out the E train, which takes 40 minutes from Jamaica Center to 42nd St on a good day. If the E was extended, the total trip would take almost an hour.

However, the E, being a subway ride with a free transfer, attracts far more ridership than the LIRR does presently. The E already runs at 12tph to Jamaica Center-Parsons/Archer. As stated before, some E trains must begin at 179th St due to capacity limitations at Archer Ave. Should the E be extended, it would automatically have more service than the Atlantic Branch (with regional rail service) AND be more consistent since all E trains would originate in the same place.

With the potential of deinterlining and CBTC combined, express service on the Queens Blvd Line could be more frequent and more reliable. Today the express is split between the E and F, each running 15tph. While technically speaking, CBTC is capable of 40tph, this depends on many factors. Realistically, given the interlining and terminal capacity of the E and F, a total of 36tph is probably more likely. That means the E could see 18tph with an extension to Springfield Blvd.

It’s also worth considering that with a subway extension, more service will be run on ALL lines involved. Expanding the Montauk Branch to 3 tracks will give all lines using that trunk enough capacity, or rather, increase the capacity to the same point that any greater regional rail service would. Traditional 3-track subway lines are limited by their truncation to 2-tracks. But a 3-track Montauk Line would merge seamlessly onto the Main Line east of Jamaica so that all 3 tracks can run full service (full service once interlined branches are considered.)

Therefore, expanding the Montauk Line to 3-tracks and extending the E train to Springfield Blvd provides the greatest amount of service for the overall network. It obviously costs more, but it seems like an investment that makes sense. There is already high bus-to-subway ridership and enough potential redevelopable land to return on the investment.

In terms of cost, the 1978 estimate was, adjusted for inflation, $611 million. While not a 1:1 comparison, if we were to use the costs for the LIRR Third Track, the new estimate would be $950 million. The Third Track project involved a number of expensive grade eliminations which the SEL would not have to deal with. By a wonderful coincidence, almost all the tunneling which would be needed to extend the E was completed in the 1980s. There would need to be a small connection made between the existing tunnel at Tuskegee Airmen Way to the LIRR ROW, but this is accounted for in the cost.

This means that this is possibly the only subway expansion project in NYC that would cost less than a billion dollars. With the potential for development, especially just south of the LIRR Main Line and York College, this project could easily pay for itself with development.

I don’t believe that as many, if any, homes would need to be taken for this project to be built today. Most of the private property was designed for elaborate station entrances and parking. The stations today do not need to be complex and their mezzanines/entrances can be built within the limits of the embankment. It may be possible to build the stations with elevators and stairs going over the tracks. I would also throw out any proposed parking lots, in favor of building denser housing around the stations. Bus drop-off zones would be needed, but could be done in a far simpler way than cutting new streets into private land.

No clear answer

The question we have to ask is what the true desire might be? That is, are we aiming to simply provide more and better service, or are we looking for a redevelopment tool? In strict terms, creating a better bus network that provides free transfers to the LIRR, and providing more LIRR service with free transfers to the subway is the most affordable and equitable solution. It’s also something that the MTA seems to struggle with, and limits the potential of future growth. A fully built out SEL provides the most amount of service on two networks, which will support more development, but will cost far more.

There is no clear answer here. Regional rail advocates rightly point out that the high costs of MTA construction might prohibit any subway extension, especially one along an existing rail line that could see better service for a fraction of the cost. But the extension brings system-wide benefits. I tend to fall into the “more is better” category, and I think that the SEL project would have a much greater impact on changing land use, reducing car dependency, and creating a more sustainable city than simply improving LIRR service. But that is a much bigger ask, especially when redevelopment doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and capital dollars are limited.

Either a more integrated fare structure or the E train extension. Since this area is a transit dessert extending the E train makes the most sense.

Maybe incorporating other Queens projects such as the Lower Montauk and the Rockaway Beach/Rego Park projects will finally bring the transit miles per person in Queens up to an acceptable level.

I thought extending the F train deeper into Queens would be helpful, but extending the E would be even better! It would bring subway service to a completely new area and shorten commutes for many people coming from eastern Queens. With such a low price tag, this project should be built in the near future!!

The F would be helpful too, but it comes at a much higher cost.

This was an excellent summary of the history of plans to serve this part of the city.

I agree with your conclusion, a very effective way to bring transit to this area would be by widening the Montauk branch to 3 tracks so all LIRR services can be accommodated there, and then allowing E trains to run on the existing Atlantic branch right of way to provide a frequent connection for much of SE Queens.