In the annals of New York infrastructure history, projects like the 2nd Ave Subway loom large. But while 2nd Ave has progressed, and other projects like an Utica Ave Line or Rockaway Beach Branch get their cans kicked down the road once a generation, one unrealized dream looms like a mountain beyond the horizon: a tunnel to Staten Island.

Staten Island is the southernmost point in both New York City and New York State. Added to Greater New York City in the Consolidation of 1898, even today it feels distinctly different from the rest of the city; more suburban and more conservative.

A story often retold, though at this point assumed to be completely fabricated, tells that Staten Island was the prize in a boat race between two sailors to see which colony, New York or New Jersey, would own the land. In reality, comprising one half of the entrance to New York Harbor made the island an important strategic asset for New York.

When the City of New York gobbled up Kings, Queens, and Richmond counties (the name of the county was officially changed to Staten Island in 1975), it did so with the promise of infrastructure investments such as new bridges and, most importantly, water from the Croton Aqueduct. Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx (which had been partially annexed by New York in the 1870s), all saw relatively quick investments. The first subway line opened a mere 6 years after consolidation and by 1938 three separate systems had been built to unite the city.

That is, except for Staten Island.

Give the ability for new rapid transit to transform farm lands into subdivisions (as evident by the massive growth in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens in the 1920s), one would assume that the same would have held true for Staten Island. In fact many developers were promoting homes on the island with the assumption that a tunnel between Brooklyn and the island was imminent.

Like all good boosters, Staten Islanders dreamt big. Multiple proposals for a rail tunnel were created between the 1880 and the 1930s. Initially, a tunnel was thought too ambitious as the technology of the time was so new. Once electrification became standard and tunnel technology advanced, it seemed like a connection was in reach. One tunnel was even started, only to be filled back in when funding dried up. Ultimately, it was a bridge which put the final nail in the coffin for a serious tunnel to the island. It is, therefore, ironic that the home of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the titan of the New York Central Railroad, was never connected to the rest of the city by rail.

The Railroad

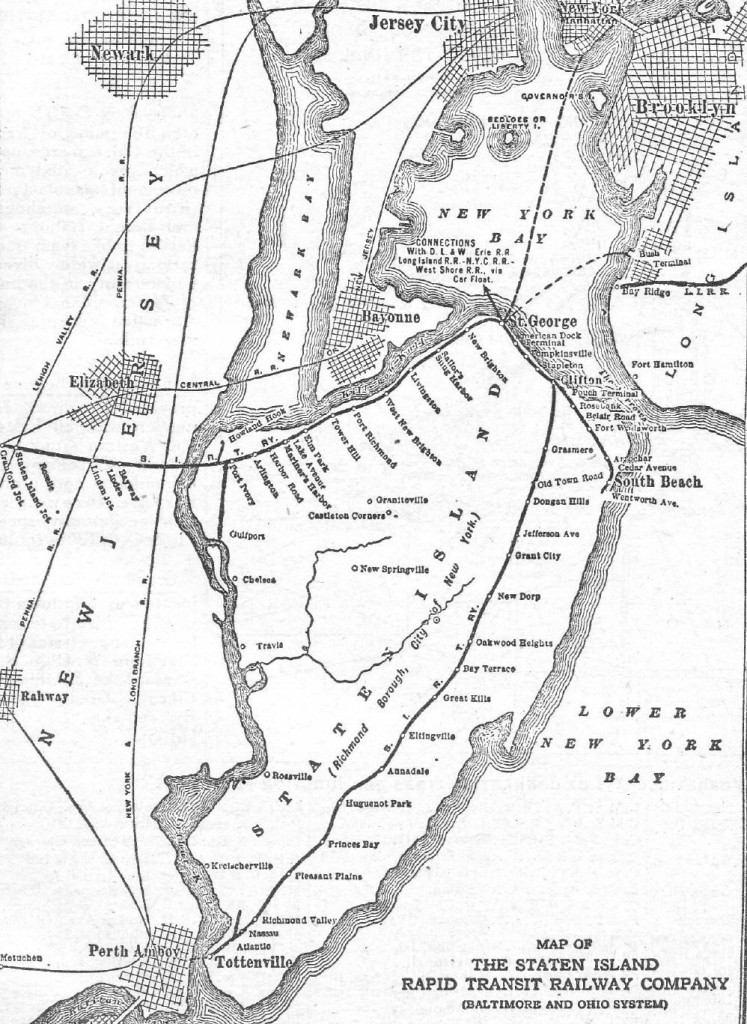

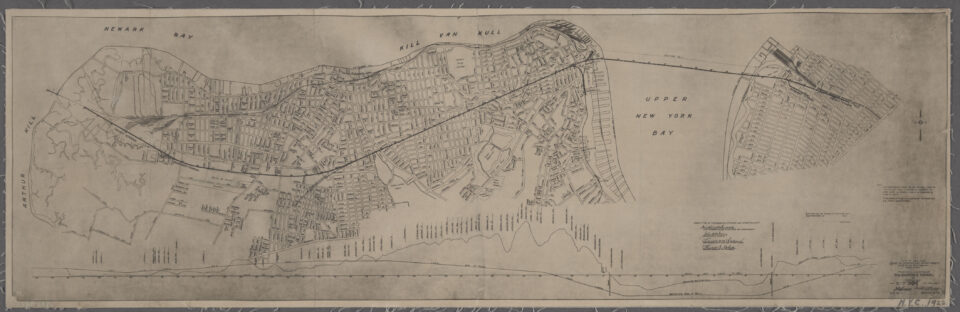

Though often forgotten by the majority of New Yorkers, Staten Island does, in fact, have a railroad; the Staten Island Railroad (today, Railway) opened in 1860 between Tottenville and Vanderbilt Landing (today, Clifton station). Built and operated by the Vanderbilts, the rail line worked in conjunction with ferries to New Jersey and New York. In 1871, a ferry docked at Whitehall Street Terminal exploded due to a faulty boiler, killing 85 people. The company went into receivership and eventually purchased by a competing ferry operator George Law, who split the rail line from the ferry operations.

The railroad passed through various companies until the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (B&O), looking for an entry point into the New York market, partnered with a local real estate developer, Erastus Wiman, to buy out the railroad, expand new branches into the island, and consolidate all ferries at one new terminal. The land proposed for this new terminal was owned by George Law, who wasn’t interested in giving over the rights. As a way to soften Law up, Wiman proposed calling the new terminal “St. George”. Law signed over the option on the land.

The B&O finalized control of the railroad in 1885 with a stock buyout. It was trying to compete with its main rival, the Pennsylvania RR, which at the time terminated in Jersey City. To do this, the B&O built the North Shore Branch, connecting Elizabeth, NJ with St. George Terminal. Because of the hilly terrain of the island, land along the shoreline had to be filled in through New Brighton and Snug Harbor. The branch opened in 1884.

In addition to the North Shore Branch, a South Beach Branch was added in 1888. Branching off the Main Line at Clifton Junction, it was originally planned to run south to Oakwood Beach, but the railroad couldn’t get the land rights from the Vanderbilt family, so the line ended at South Beach.

The First Tunnel

While the railroad had certainly helped Staten Island develop, Wiman knew that the only way to truly get people to move to the island was to connect it to the growing city across the bay. Ferries could only do so much and still required multiple transfers to different private rail lines.

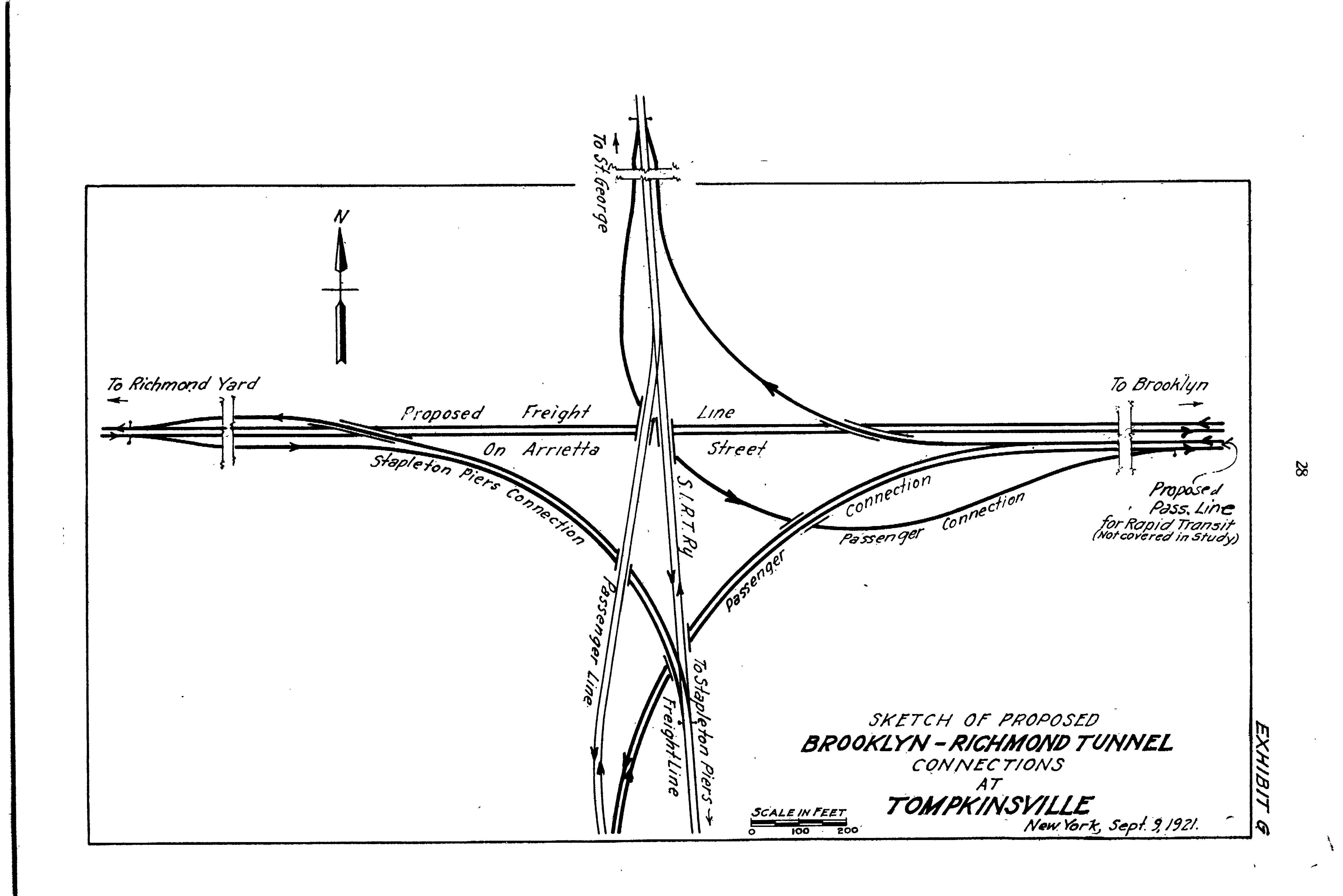

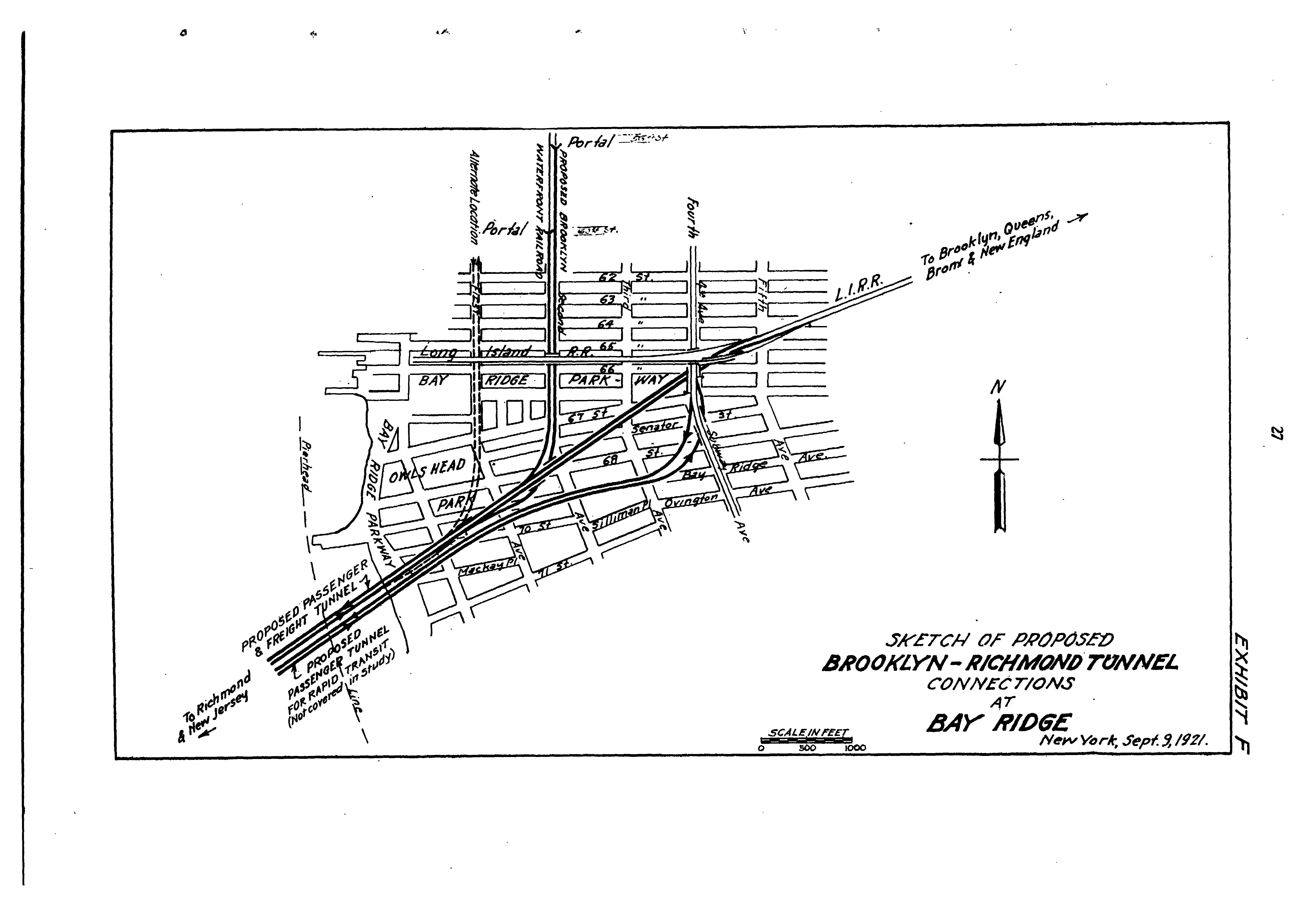

The railroad proposed a tunnel that wasn’t simply going to span the harbor, but was part of a new passenger and freight trunk line. Due to the uneven geography in the interior of the island, the railroad recommended building a tunnel straight through the hills. The new line would have begun at the existing Arthur Kill bridge but run southeast to a point paralleling Forest Ave. It would have run east until it reached Clove Lakes Park where it would tunnel straight to St. George. Here the tunnel would split so that a connection to the Main Line could be made, while two tube would be dug below the harbor on their way to Bay Ridge. A passenger terminal would have been built at 4th Ave and Senator St (allowing transfers to the BRT 3rd Ave El) and a freight terminal would have been built to the east, parallel to the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch. The tunnel was limited by technology and financing, but the idea lay the groundwork for subsequent tunnels to follow.

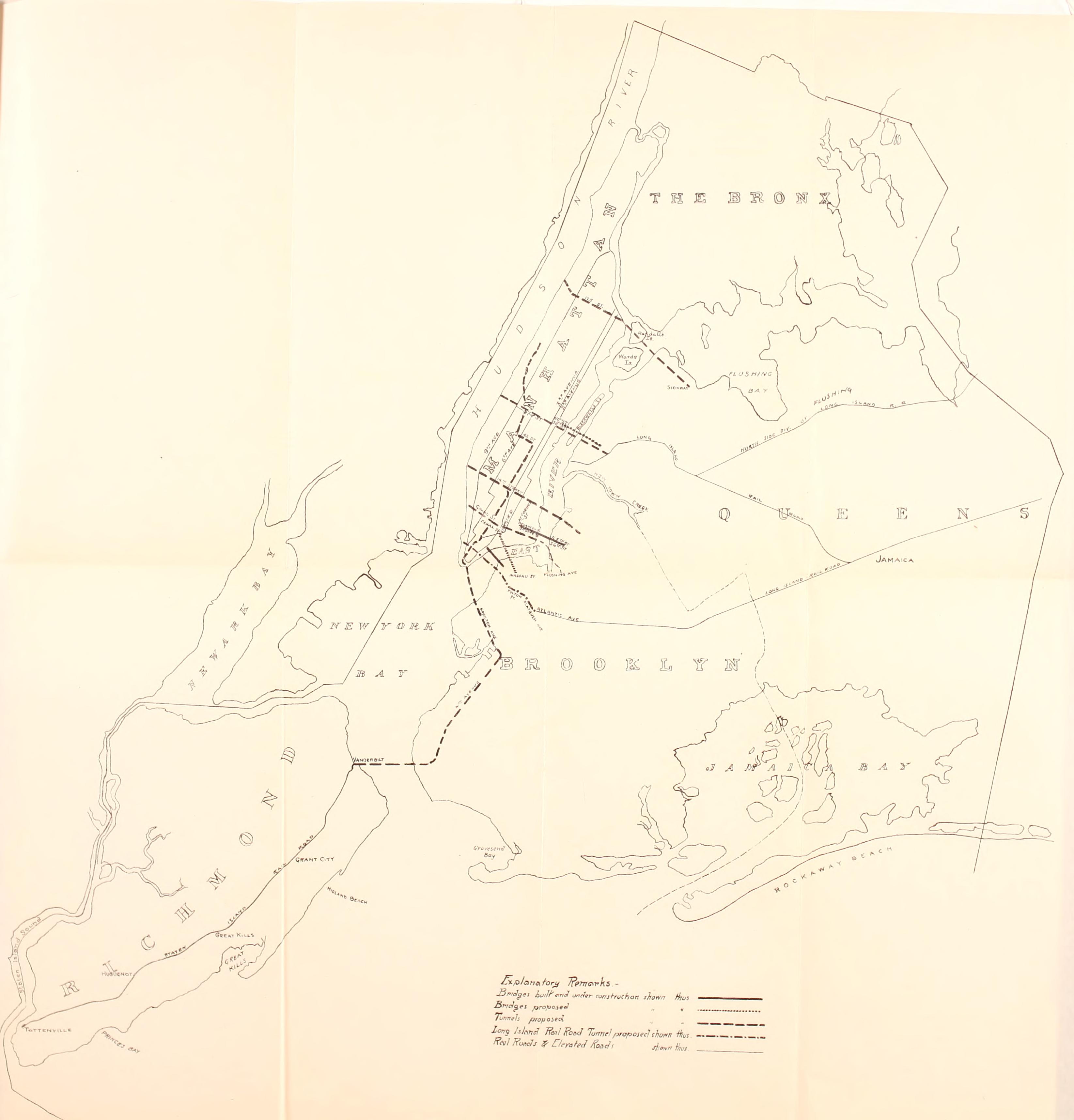

As part of the city consolidation, engineers drew up plans for new bridges and tunnels. The success of the first subway in 1904 showed that electric underground trains could be successful in transporting large numbers of people and spur development. Even before the first subway was extended into Brooklyn, planners were dreaming up ways to connect Staten Island with subway trains.

The first wave of subway plans for Brooklyn centered around the 4th Ave Trunk Line and the Brooklyn Loop Line. The Loop, which would have connected the Brooklyn, Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges with a subway through Bedford-Stuyvesant was dropped in favor of radial lines, but the 4th Ave was promoted.

The 4th Ave Subway went through a number of different plans. In Manhattan, the Interborough Rapid Transit Co. (IRT) had a monopoly, but in Brooklyn the home-grown Brooklyn Rapid Transit Co. (BRT) owned and operated all the existing elevated and streetcar lines. A tug of war soon ensued between the two companies over who would get the rights to the new lines.

The IRT, which was already building its first extension to Atlantic Ave, changed its plans to accommodate any new lines it might be able to control. This subway, today the 2,3,4,5 between Borough Hall and Atlantic Ave, was expanded to allow for a connection over the Manhattan Bridge, a branch down Lafayette Ave, and a branch down 4th Ave.

To counter this, the BRT proposed building lines in Manhattan, up Lexington Ave and into the Bronx, as well as a new line-up Broadway and into Queens. The BRT had an extensive network of elevated lines in Brooklyn and wanted to extend those into Manhattan.

The IRT proposed its own subway to Staten Island, albeit avoiding Brooklyn entirely. Two plans were drawn up, the first would extend the original subway straight under New York Harbor to St. George, and the second which would have extended the subway to New Jersey and then down through Bayonne before connecting to the island. The first was, and probably still is, impractical, and the second would have required the IRT getting the rights from New Jersey, which would have been difficult.

Acting as a mediator, the city drew up the Dual Contracts. Expansion would be split between the two companies based largely where each already had sway. The IRT could extend its Brooklyn line deeper into the borough, but past where the BRT had service; along Eastern Parkway and into East Flatbush. The BRT would control the new 4th Ave Line and use it as a trunk for the old steam railroads, which it would convert into new elevated lines. The West End and Culver Lines ran along city streets, so these needed to be elevated, but the Sea Beach ran along a private right-of-way, so it was moved into a trench below street grade.

The Manhattan Bridge had been built with 4-tracks for use as subways, but had opened before any decision was made as to who would operate the trains. Ultimately the BRT won out. But because the tracks had been built on the “outside” of the bridge, rather than down the middle, they would require a complex interlocking to be built to connect the two sides. To save money, the BRT built a more simple interlocking where trains would have to pass in front of one another, causing delays.

The Dual Contracts stipulated that certain lines had to be built and allowed for other branches to be built at a future date. These included the IRT Utica Ave Branch, and BRT Crosstown Line (which would have been an elevated line running from Queensboro Plaza, through Greenpoint and Williamsburg, down Franklin Ave and connecting to the Brighton Beach Line to Coney Island), and the Staten Island Branch.

4th Ave Subway

When the city set out to expand its subways, it did so with a general idea of what they wanted, but would often change their plans midway through. This happened to the IRT Brooklyn extension, the Centre St Line, and was the case when building the 4th Ave Subway.

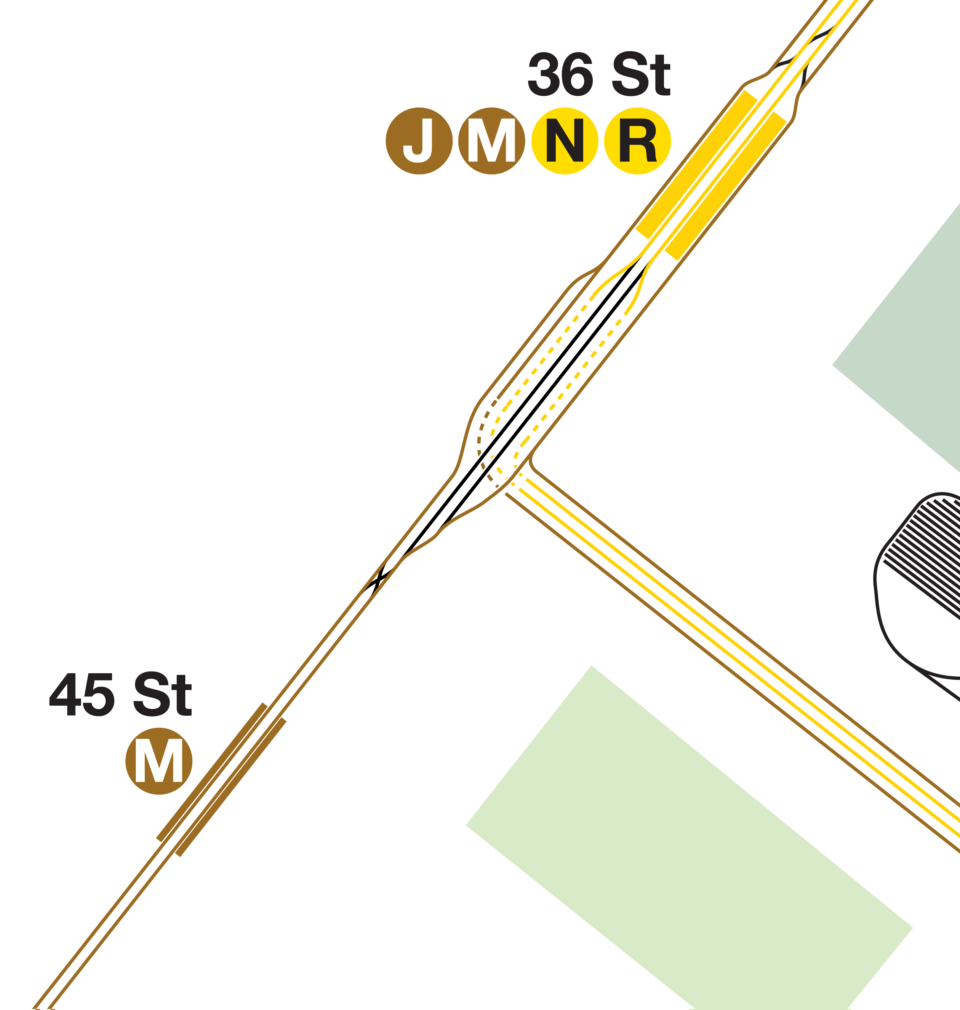

The original Dual Contracts plan called for a 4-track trunk line running south from Atlantic Ave to 36th St. South of 36th St would be built a large flying junction, where the 4 tracks would split into 7, and the 4 new tracks would turn east along 40th St into a new 4-track subway down New Utrecht Ave. When this subway line was dropped in favor of building the elevated West End Line (today, D train), the flying junction had already been constructed. A new, smaller, junction was built with two tracks.

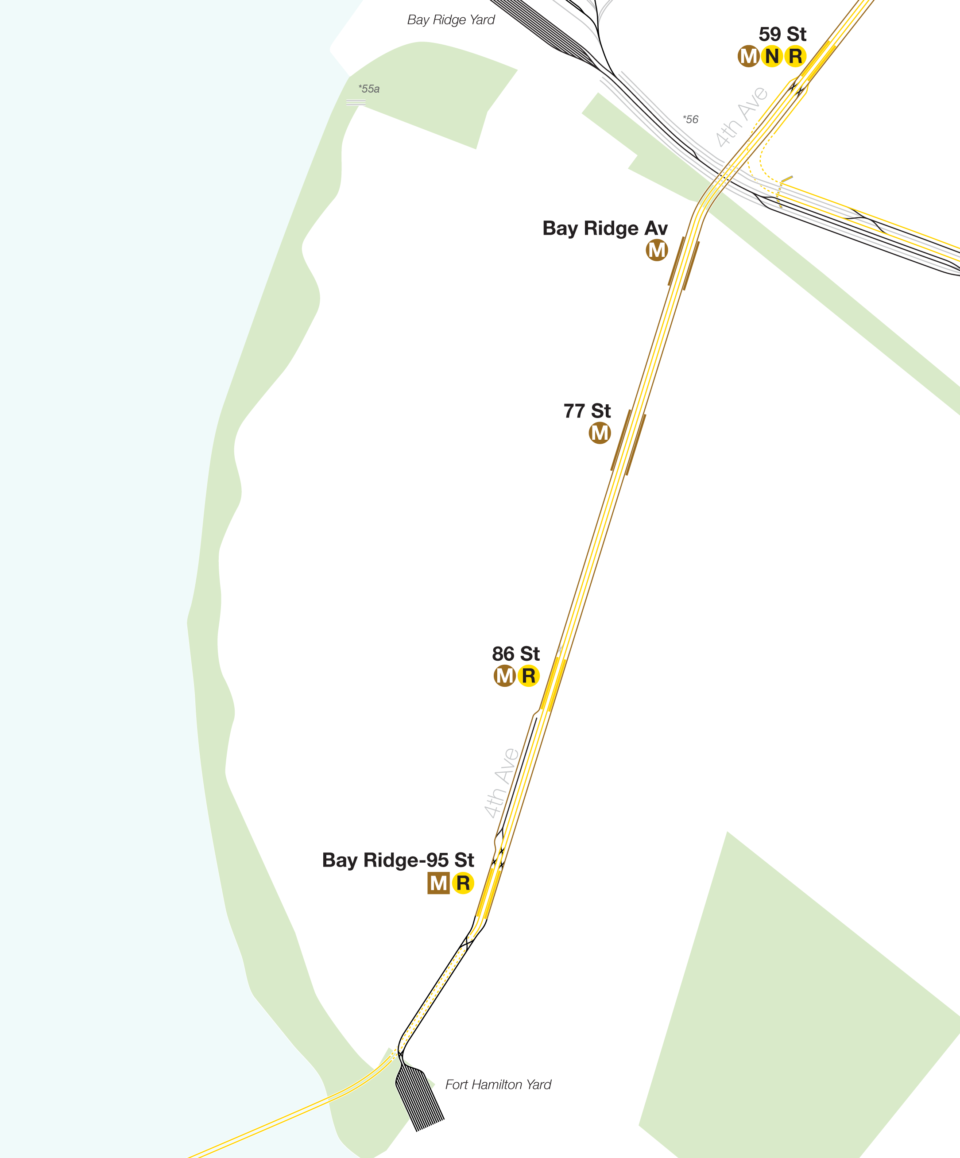

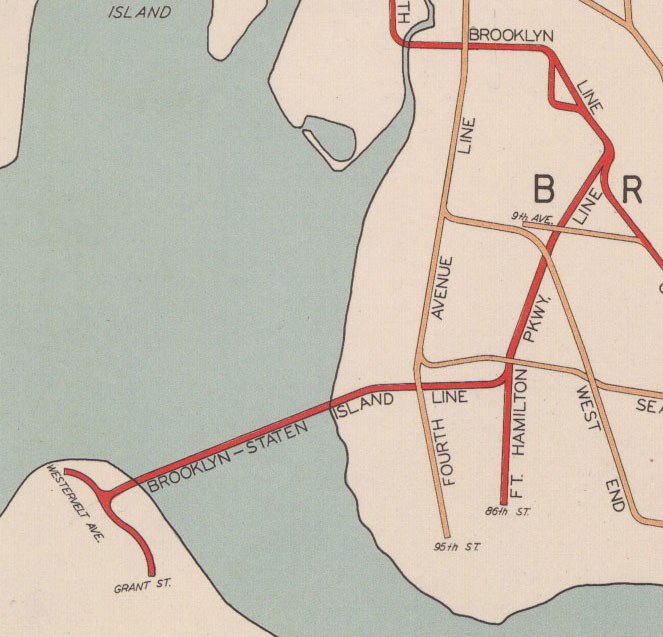

South of this junction the subway was going to be built with 2-tracks on the west side of 4th Ave south to 101st St. This was to allow for two more tracks to be added later. Once it became clear that there would need to be more service, the east side tracks were added back to 59th St. At 59th St, the Sea Beach Line was added to the line with a direct connection to the express tracks. The local tracks were to have two branches, one south to Bay Ridge and one to Staten Island via a new tunnel.

Similarly to the previous concept, the Bay Ridge branch was built with 2-tracks on the west side of the avenue to allow for two more tracks to be added to the east side at some future date. The original terminal was at 86th St, but was planned to be extended south to 101st St where a 16-track yard was to be built (it is not clear if this yard was to be built under John Paul Jones Park or along the waterfront, which is now park of the Belt Parkway.)

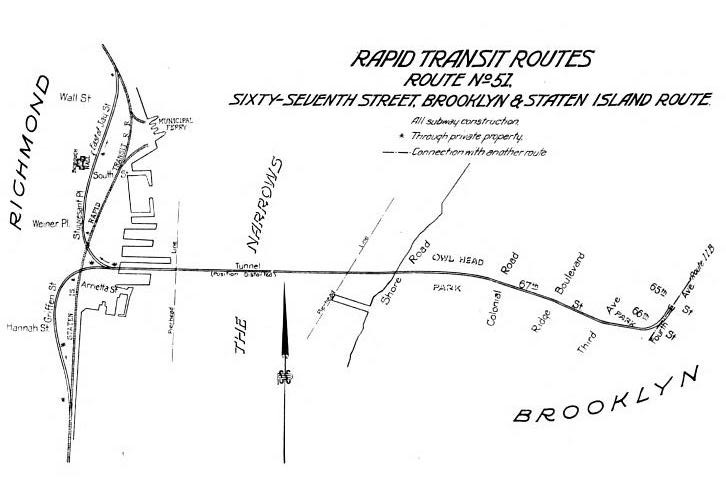

At the time there were a few ideas for how to connect this subway to Staten Island. The northernmost connection would have used the tunnel provisions at 59th St station and turned west under 68th St. On the island, the line would have split into two branches, one to connect to the North Shore Branch and the other to the Main Line and South Shore Branches. The second was to build out the second set of tracks on 4th Ave in Bay Ridge and extend the tunnel through Fort Wadsworth and somewhere into the island (presumably connecting to the Main Line at Grasmere). Going off of all historical data, the northern alternative was the only one seriously considered.

Subway vs. Railroad

Planning for the northern tunnel through Owl’s Head Park began in 1912, when the city proposed a tunnel which would include two 40-inch water mains. This would have required paying off the Pennsylvania RR, which operated the LIRR at the time, and had purchased the B&O, which still operated the SIR.

The tunnels would have been the longest underwater tunnels ever built at almost 2 miles long. One version of the plan included two sets of 2-track tubes: one for rapid transit and the other for LIRR passenger and freight. The plan would have been similar to that of the 1880 B&O tunnel, connecting to the Main Line and building out a new trunk line deeper into the north shore of the island.

In 1922, Mayor John Hylan (no friend to the private rapid transit companies), proposed a stripped down tunnel. It would have 2-tracks and serve both rapid transit and freight. At the time, Jamaica Bay was being looked at for a huge industrial port. Connecting freight rail from New Jersey through Brooklyn was going to be critical in its development. While the edge of the bay would be redeveloped in sections, the entire seaport project was eventually killed by Robert Moses in 1949 when he was able to secure the land (and water) for the natural preserve.

Hylan thought that passenger service alone could not justify the expense of the tunnel. But the Transit Commission didn’t want to share the tunnel with freight. The Pennsylvania RR saw the idea as encroachment into its territory and opposed the tunnel as well. They had friends in Albany, including then Governor Al Smith (who owned stock in the company.)

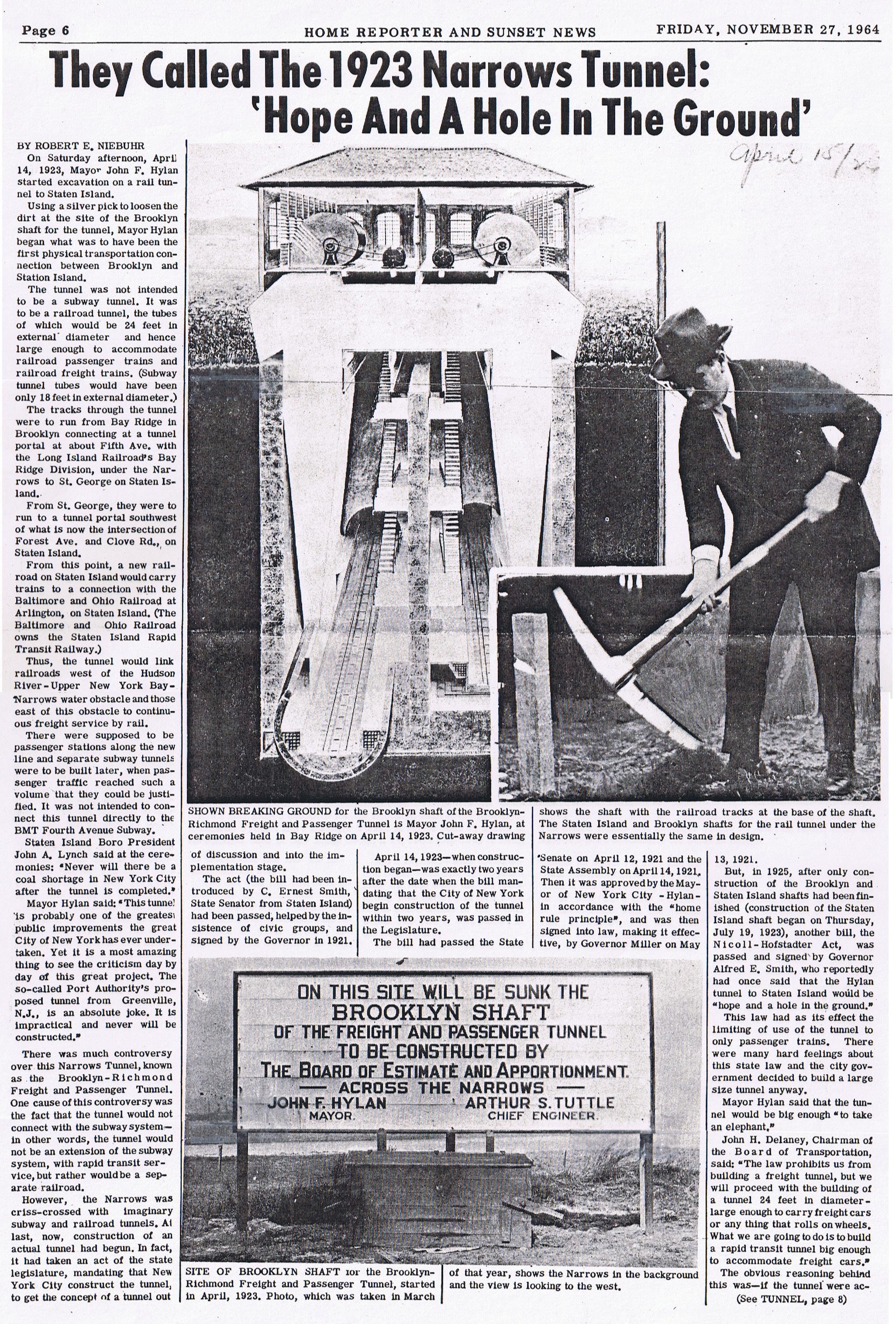

Hylan made the first move by publicly holding a groundbreaking ceremony on April 14th, 1923 in Owl’s Head Park in Bay ridge. A shaft was sunk close to Shore Road and over the next two years workers began to excavate. However, in 1925, the project was canceled, and the staff were laid off. Officially canceled due to lack of funding, an agreement had not been reached between Hylan and the Board of Transportation regarding freight though the tunnel.

Oddly, the southern option seemed to make some progress. While the 4th Ave Line originally terminated at 86th St, it was extended one stop south to 95th St in preparation for a tunnel to Staten Island. The plans to build a yard were scrapped, but the 95th St station was built with false walls at the southern end for some future connection.

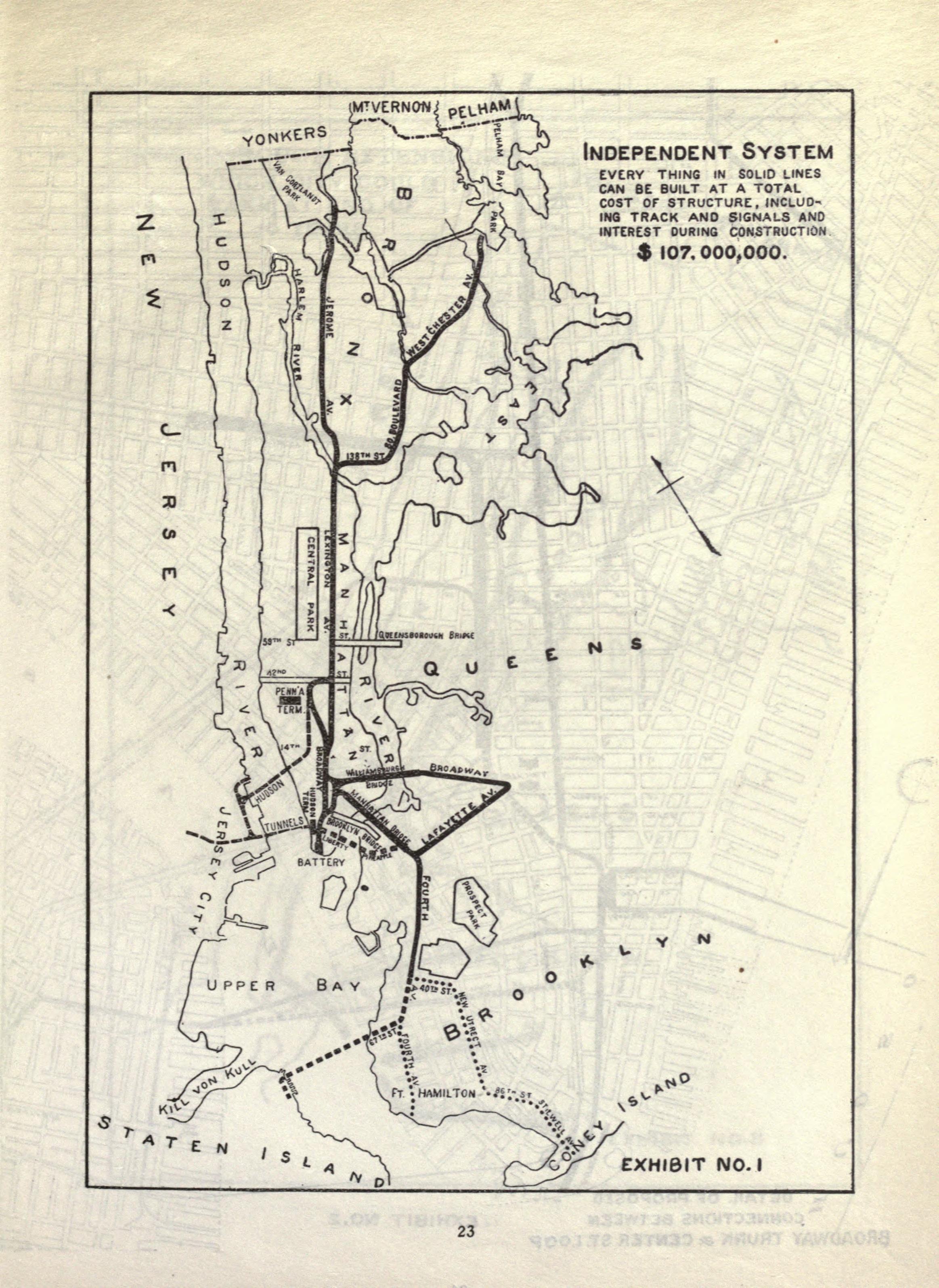

Hylan was trying to keep the new tunnel out of the hands of the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Co. (which had taken over the BRT after it had gone bankrupt in 1923.) Hylan famously held a grudge against the BRT after he was fired (wrongfully, he claimed). As Mayor, Hylan sought to create a new, independent subway system to compete with the private companies. Many of the proposed subway extensions which would have been operated by the IRT or BMT were instead transferred to the new Independent Subway System (IND).

After Hylan resigned as Mayor, the Staten Island tunnel was shelved. The Pennsylvania RR had countered with their own tunnel directly between Brooklyn and Bayonne, which henceforth was known as the Cross Harbor Tunnel. In 1927 the Holland Tunnel opened and showed that subaqueous vehicular tunnels were technically possible. Plans shifted from rail to road for any new tunnels with vehicular tunnels proposed for both 68th St and Fort Hamilton. In 1929, the IND Second System report showed a proposed tunnel between Fort Wadsworth and Fort Hamilton.

IND Plans

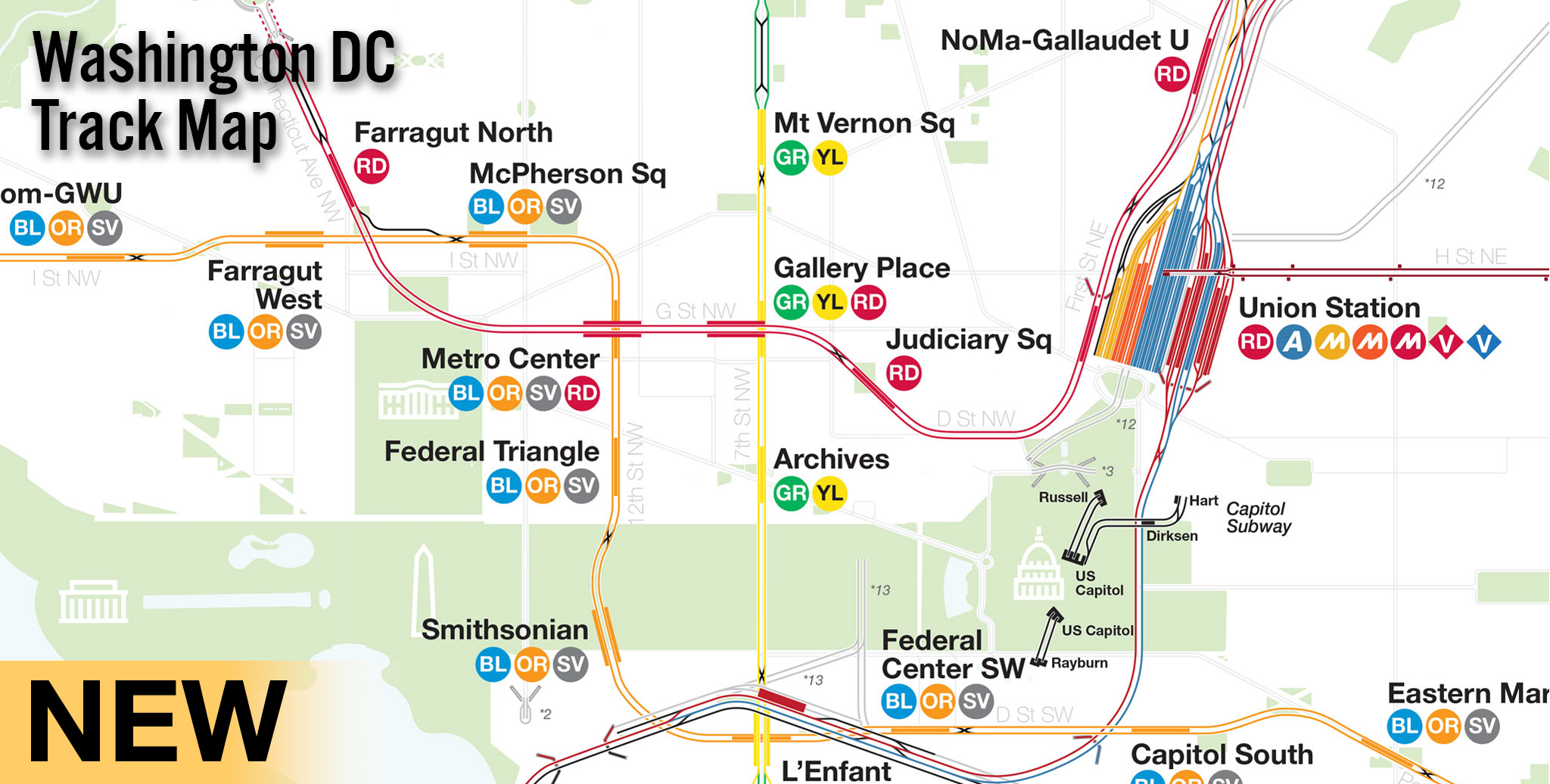

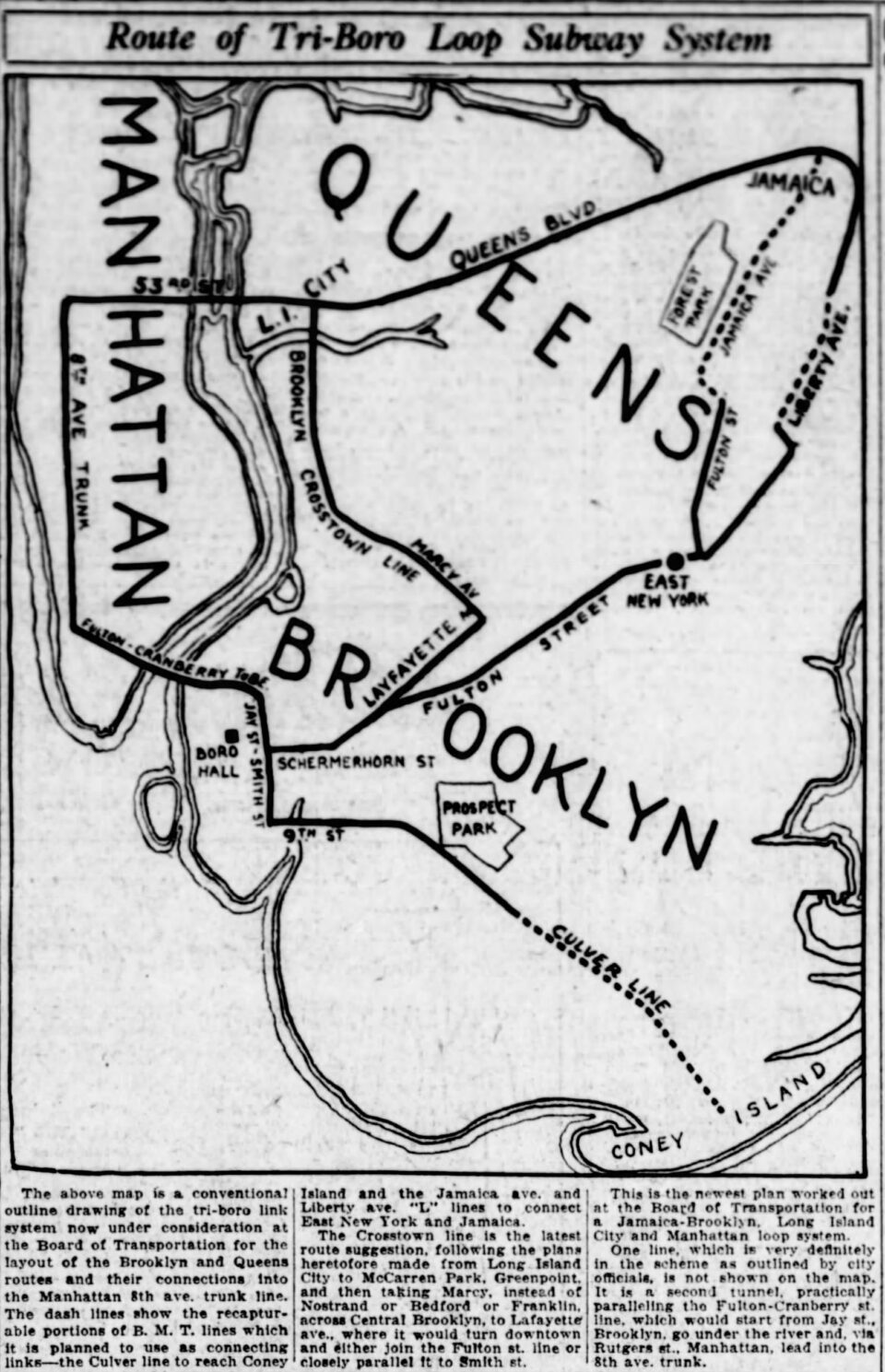

While the grand plans of the Dual Contracts fell into history, the new kid in town was proving even more ambitious. All plans for new lines were transferred to the IND which was putting together its own unified system. The proposed system would be built around the 8th Ave Line with branches to Jamaica through Queens and Brooklyn, a combination of the Crosstown and Lafayette Ave Lines, and a branch to Coney Island over the BMT Culver Line (today, F train) which was to be “recaptured”. As this line had been built by the city, with service operating on a lease to the BMT, the city could buy out the contract and take the line back.

One of the reasons that the IND was so keen on taking back the Culver Line was that the 4th Ave Line had been crippled by poor interlocking design and too many branches. 5 branches fed into the DeKalb Ave station complex. While not by itself a problem, the tracks and switches connecting these lines were designed with at-grade crossing. This forced trains to change from one line to another in front of one another, severely limiting capacity. Add to this the complex service patterns that the BMT ran (various combinations of local and express trains on the same tracks, lines only running one way, rush hour only trains, etc.) meant that each branch had rather abysmal service levels.

The best solution was to rebuild the interlockings off the Manhattan Bridge with more complex (read: expensive) flying junctions. The BMT wasn’t interested in this. (This interlocking was eventually rebuilt in the late 1950s.) So the other option was to remove a branch entirely, freeing up capacity. The best candidate was the Culver Line which ran geographically between the Brighton Beach Line and the other branches of the 4th Ave Line. With its central location, the IND figured it could siphon off ridership from the other BMT branches. It also lined up nicely with its South Brooklyn Line which the IND had been planning to run through Park Slope and Windsor Terrace.

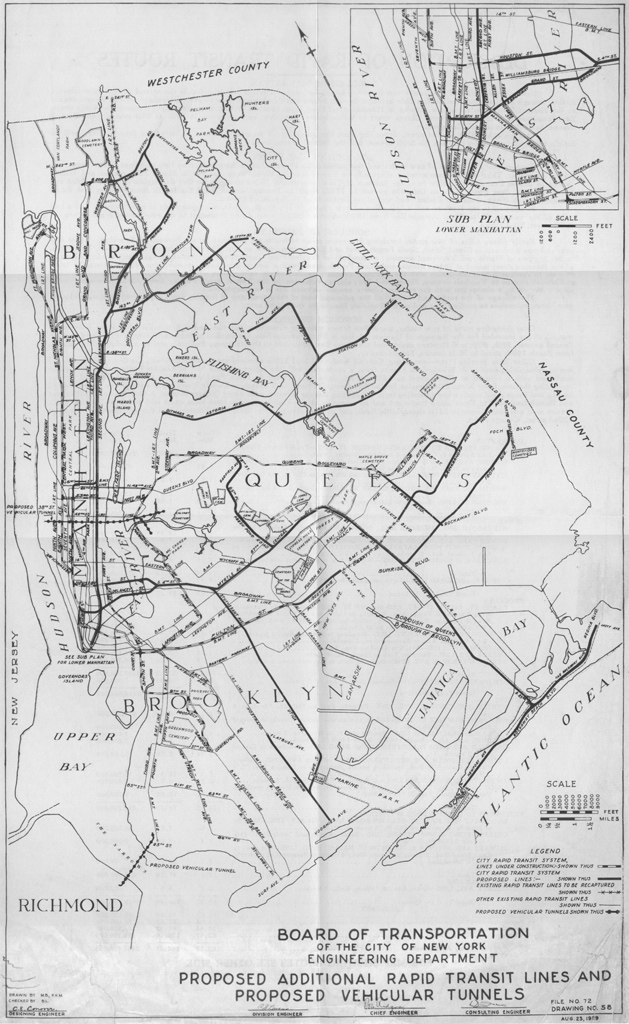

The IND began to build out its network and by 1929 work had progressed to the point where planners were confident that they could expand their system to cover the entire city. A vast expansion plan was released, known as the Second System. Interestingly, no rail tunnel to Staten Island was proposed. Not that it mattered as weeks later the stock market crashed and ushered in the Great Depression.

The city was able to get funds from the Federal government to finish the original IND already under construction. Many of the lines opened between 1932 and 1936. While these lines were being built, planners dreamt of ways to expand the system further.

By 1939 much of the original system had opened and planners could get a better idea of how riders were using the lines. The South Brooklyn Line, which had been built to Church Ave, was underperforming due to the fact that the elevated Culver Line had not yet been recaptured. While this was still the ultimate goal, the line would probably run with lower than predicted ridership even once Culver was connected. (Even today, the F train has fewer riders south of Church Ave, and fewer riders than the D train, which it parallels.)

The South Brooklyn Line was built with 4-tracks between Bergen St and Church Ave. Two tracks ran into Manhattan (originally this was served by the E train before the 6th Ave Line was built) and two tracks connected to the Crosstown Line through Brooklyn and into Queens. The original concept was that Manhattan-bound trains would use the express tracks and the Crosstown trains would use the local, with riders transferring at Bergen St. Higher demand for Manhattan service meant that most riders were forced to transfer. This was bad enough at most stations but worse at Bergen St where the local and express were on different levels.

Planners also knew that once the 6th Ave Line was open it would double capacity throughout the system, and they were looking for places to send these new trains. Planners had cut some lines from the 1929 plan and streamlined others. DeKalb Ave was still a problem and the IND was actively trying to take ridership away from the private companies. Staten Island still didn’t have a subway.

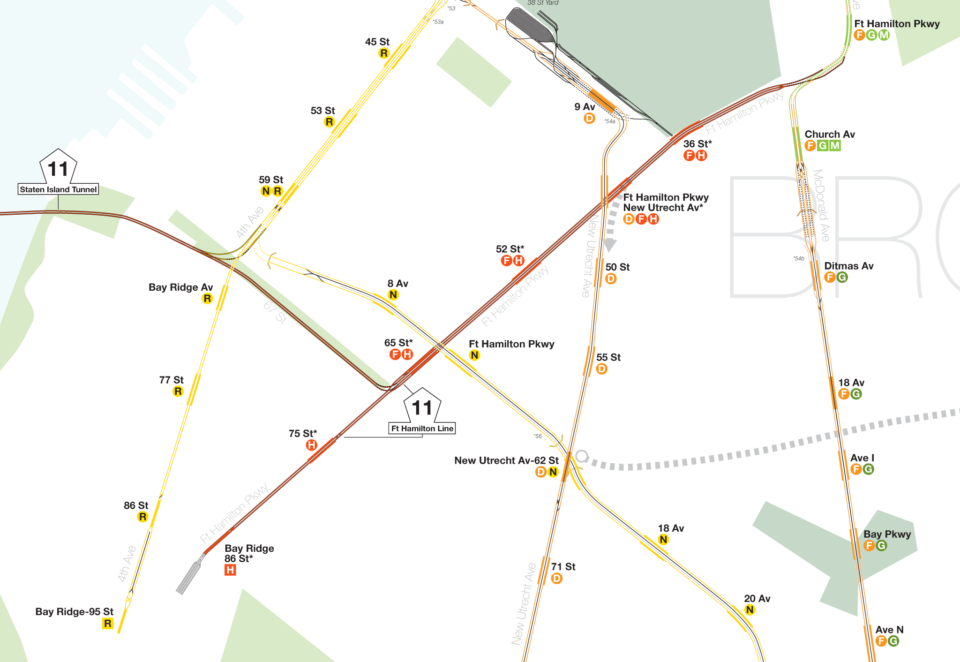

In a masterstroke, planners came up with the idea to connect the old Staten Island Tunnel at 68th St to the South Brooklyn Line along Ft. Hamilton Parkway. This new line would not only connect Staten Island, but offer faster express service to southern Brooklyn via the underused express tracks.

Contrary to popular belief, the South Brooklyn Line was not built with provisions for this branch. The subway from 9th Ave in Park Slope to Church Ave in Kensington, Brooklyn splits so that the local tracks wind through Windsor Terrace while the express tracks make a more straight shot south. Under Prospect Ave they meet, but are built on two levels (local on top, express on the bottom) and don’t meet at the same level until Church Ave station. A connection was proposed, but no actual tunnels or bell mouths were built (unlike in other locations which were built for future expansion.)

It’s hard to know just how serious this plan was since no track schematics have ever been found. The proposed line would have had three branches which would have severely limited service on each. Most likely this plan was proposed not to be built, but rather to build political support for raising funds.

The IND was expensive and overbuilt. Enormous mezzanines were the norm, especially in places where there would be no need for them. Interlockings and flying junctions were built larger and more expensive than ever before, with much wider curves to allow for trains to operate at higher speeds. The 6th Ave Line was the most expensive subway built yet, and the city was struggling to complete it. It needed to raise money and to do so it required as many people on board.

As such, many of the proposed lines weren’t actually going to be built. The IND needed politicians to think these lines would be so they would vote for continued expansion. Southern Brooklyn had loud and powerful politicians who were no fans of the BMT and its poor service. The Ft. Hamilton-Staten Island Line was the perfect way to pick up important votes.

By 1940 the city was finally able to purchase the now bankrupt private transit companies. But years of starvation had led to deferred maintenance and the subways which the city now owned were in much worse shape than they were anticipating. Expansion was pushed aside for basic maintenance and any plans for a tunnel to Staten Island were shelved for good.

Decline

While no one can argue that the Staten Island Railway (SIR) didn’t help with the growth of the island, the lack of direct service to New York meant that it would always be a second rate railroad. The B&O went bankrupt and the Pennsylvania RR bought it out in 1900. In 1928 three major bridges were opened connecting Staten Island with New Jersey: the Goethals, the Outerbridge Crossing (named after the first chairman of the Port Authority, Eugenius Harvey Outerbridge) and the Bayonne. These bridges allowed bus service to flourish on the island and, except during World War II, ridership on the SIR declined.

Ridership plummeted after the war. In 1953, service was ended on the North Shore and South Beach Branches. While some freight service remained on the North Shore Branch, the South Beach Branch was eventually abandoned and the land redeveloped.

The Last Bridge

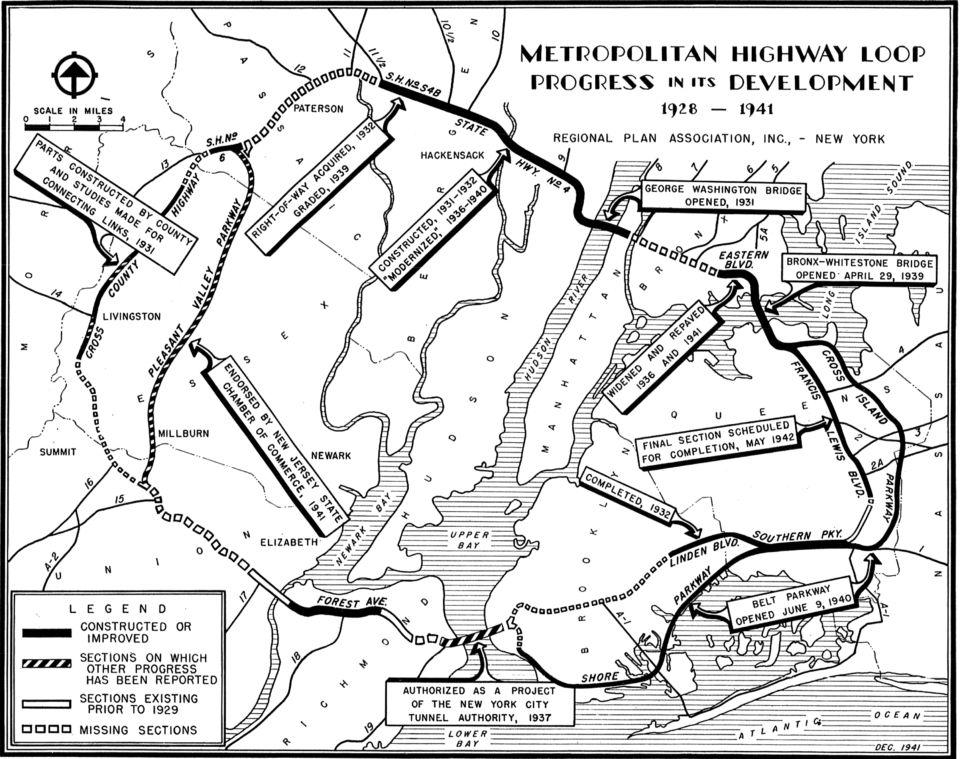

Out of the ashes of the different subway tunnel proposals came the Narrows Tunnel, a traffic tunnel between Staten Island and Bay Ridge. Traffic tunnels were seen as more feasible to build since they didn’t require long approach roads that needed to destroy the buildings in their path. Throughout the 1930s different crossings were studied, including a bridge which would have been called the Liberty Bridge.

After the War, chairman of the Triboro Bridge and Tunnel Authority Robert Moses produced a plan which showed that a bridge would be much cheaper to build and could connect to the roads which he himself had already built, namely the Gowanus Expressway and Belt Parkway. Working in conjunction with the Port Authority, which stood to gain from increased traffic on their existing bridges to the island, Moses spent the next decade putting together the permits and funding to start his bridge.

When asked if the bridge could have rail mass transit on it, Moses dismissed the idea, claiming it would cost an extra half billion dollars. Moses claimed the bridge would cost $220 million, but by the time it was open in 1964, and the second deck added in 1969, the final price tag was $342 million. That cost included the roughly 7,500 families displaced in Bay Ridge for the highway connection built to the Gowanus Expressway.

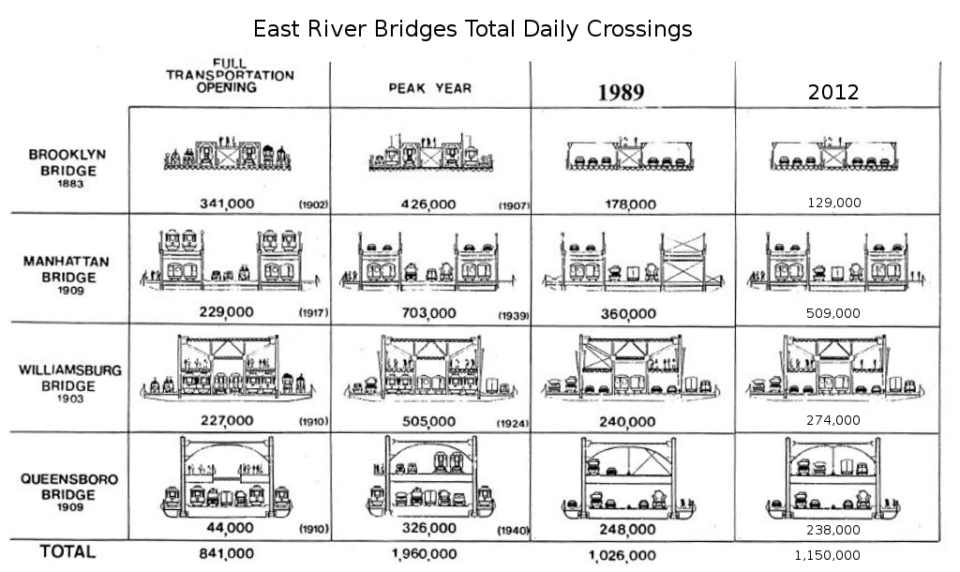

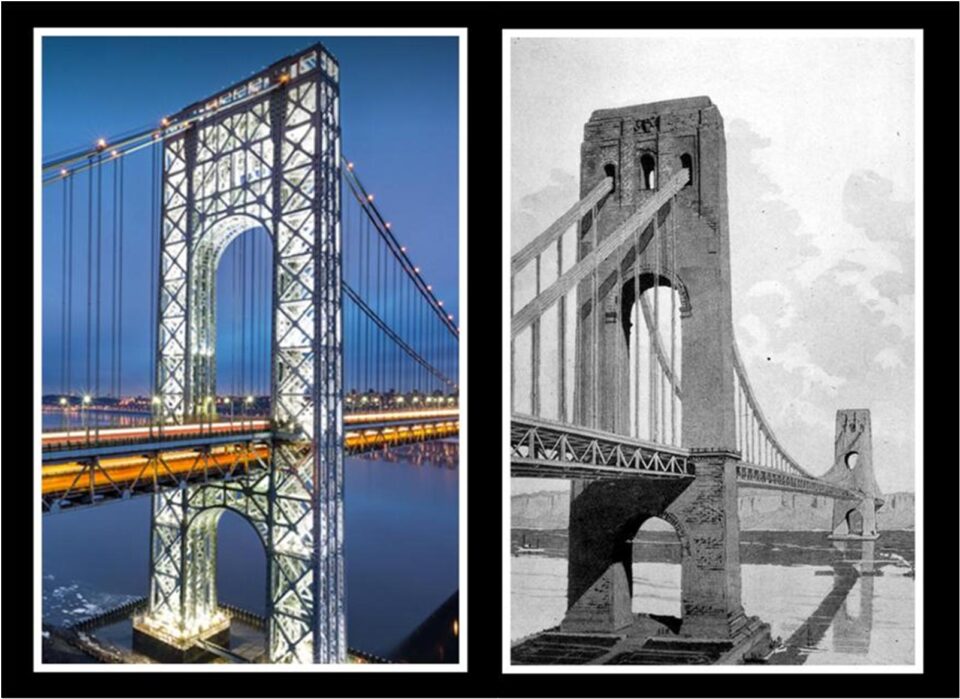

Moses was famously anti-mass transit and designed all of his highways and bridges without space for mass transit. The major bridges across the East River had all been built with space for trains and streetcars, and the George Washington Bridge was designed with a future train line in mind. After World War II Chicago expanded its subway system by building new lines down the median of new expressways. Moses deliberately chose not to do the same.

Many transit advocates have wondered if it would be possible to add a rail line over the Verrazzano Bridge. Even with two decks, it may not be possible. Bridges are designed for known loads. Car and truck traffic is relatively uniform in the loads they create as they cross the bridge. Suspension bridges are designed for these loads and sway, bounce, and flex in response to traffic crossing over.

Trains act differently. Trains are much heavier than cars and trucks (not to mention the weight of the tracks.) Because they travel less frequently over the bridge, every time they do they will be creating a moving load frequency in the bridge which must be accounted for. If the Verrazzano Bridge was not engineered for trains, then it would need to be retrofitted at an extreme cost, if it’s possible at all.

One only needed to look at the bridges which do have subway traffic and those which don’t. The Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges were built with large steel truss work to stabilize the bridge as trains cross. Trains also once crossed the Brooklyn and Queensboro Bridges, but the trains which crossed the Brooklyn Bridge were lighter (made with wooden bodies) and the bridge had been engineered for this. The Queensboro is a different design entirely. The George Washington Bridge was designed to carry trains, but it was also engineered to be covered in stone, so without the stone the entire bridge is vastly overengineered.

While beauty is certainly in the eye of the beholder, the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges are not often considered to be the best looking out there. Moses wanted his bridges to be beautiful and designed them to be sleek and modern. This meant no ugly truss work. This backfired on the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge which didn’t take horizontal wind forces into account and had to have a retrofit added so as not to blow over. The Verrazzano was designed with a supportive truss system to strengthen it in the high winds off the ocean and for when the second deck was added a few years after it opened.

Moses may very well have been the last chance we had to connect Staten Island with Brooklyn via rail. In the years after the Verrazzano opened, the population of Staten Island exploded. But it did so based around the car. Suburban development makes it harder to easily add in new rail lines, not to mention that most of the corridors have now been developed to the point where any serious plans for a subway would be extremely costly.

Worse, with an auto-centric land use pattern, any rail line will be competing with the car. This almost brought the SIR to its knees even before the Verrazzano was built. The MTA operates the SIR with virtually no fares if one rides within the borough (one must pay at St. George when transferring to the ferry.) The structure of the island was cemented when Moses killed any rail on his bridge.

This hasn’t stopped dreamers from trying to come up with ways to extend some kind of rail to the island, though, nothing official has ever been proposed since the 1930s. Some have suggested rail tunnels directly under the harbor. While tunnel technology has progressed throughout the 20th Century, the cost of this would be far too great for the levels of riders. Some have looked as off ways of connecting the subways in Brooklyn to Staten Island, but the costs may still be too high. A more plausible connection is the idea to extend the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail from Bayonne over the Bayonne Bridge into the northwestern section of the island and along the west shore. But this has never been seriously studied.

A tunnel, but not that tunnel

When the B&O first proposed a rail tunnel crossing in 1888, its main rival (and soon to be owner) the Pennsylvania RR countered with their own tunnel directly to New Jersey. This is impressive because their North River and East River Tunnels through Manhattan, and Penn Station, wouldn’t be built for another 25 years!

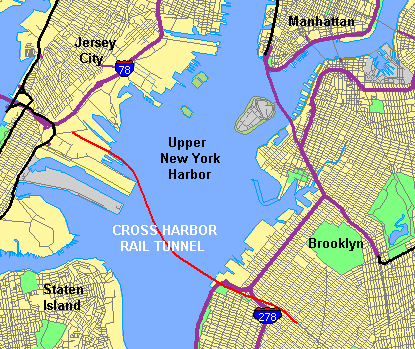

The Penn survived and so too did their idea for a Cross Harbor Tunnel. Since the beginning of the railroads, up until today, the way freight trains get from New Jersey to Brooklyn (and even Manhattan back in the day) is to roll the cars onto barges and float them across. This service is still run by the NY NJ Rail LLC, owned by the Port Authority. Rail cars get floated to the 65th St Terminal in Sunset Park and run down the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch to Fresh Pond Yard in Ridgewood, or up to the Bronx to Oak Point Yard.

Due to the complexity of the operation, there aren’t that many trains per day. The alternative is to send trains up to Selkirk, NY (south of Albany) and back down to the Bronx. This is the closest rail crossing to New York City. Freight rail is not allowed (nor would fit) through the North and East River tubes (through Penn Station.) As such, most freight that moves through New York does so on trucks.

While this truck traffic pays the bills for the MTA and Port Authority from tolls, these heavy vehicles do more damage to bridges, highways, and roads than cars, which often outnumber trucks 10 to 1. Trucks are a major source of local air pollution. Therefore, if a freight tunnel could take thousands of trucks off the road, the city would be better for it.

The chicken and the egg problem is that freight traffic is not like passenger traffic. If we were to build a tunnel between New Jersey and Brooklyn, freight traffic would increase, but it wouldn’t be the same as if it was opening up land for residential development. There is very little demand for passenger service between Newark, Bayonne NJ and Brooklyn.

Residents along the line had opposed the tunnel on the grounds that the more frequent diesel freight trains would add to local air pollution. This could be addressed with modern electric trains, but that would add to the cost of the tunnel. On top of that, any freight destined for New York itself would still need to be transferred to truck. This operation requires enough space to load the trucks and New York just doesn’t have that. So the freight traffic that would benefit the most is long haul, going to New England. And for that, heading up to Selkirk isn’t much of an issue.

This isn’t to say that the Cross Harbor Tunnel isn’t a good idea. Just that it might not be able to justify the cost. The original tunnel was proposed when Jamaica Bay was going to be redeveloped into an industrial center and even then it was going to cost a lot. Today, when manufacturing has left the region, it’s even harder to justify. A combined passenger and freight tunnel doesn’t make as much sense between NJ and Brooklyn as one between NJ, Staten Island and Brooklyn, but the North Shore Branch has been abandoned and partially consumed by the sea.

As a personal aside, when I was in college I had an internship in the planning department at the Port Authority. In the cubicle next to me was a gray haired old man who every day got on the phone and talked to people about the Cross Harbor Tunnel. This was 2009. I couldn’t imagine spending my carrier working on a project that I knew would never be built. Today, NY Governor Kathy Hochul is proposing a new transit service along the LIRR Bay Ridge Branch, the Interborough Express, which would provide passenger service from Bay Ridge to Jackson Heights along this same freight line. But what many missed in the press release was that she also wanted to connect this with the Cross Harbor Tunnel. So her new transit line will have to be built to future-proof it for an increase in freight traffic coming from the tunnel.

If it ever gets built. Considering US Representative Jerry Nadler has been pushing for this tunnel for his entire carrier, I’d say it’s just another line on a map drawn to get enough votes. Seemingly, the only way a tunnel would ever get built is if New York elects a governor from Staten Island. Or Pete Davidson and Colin Jost decide to build one as a joke.

In the second half of this post I will evaluate different tunnel options to Staten Island to see if any make sense.

Cover image courtesy of Zbigniew T. on Flickr

I followed this issue for years. Your conclusion based on costs and benefits are correct. Better express bus will accomplish what a tunnel would do at a fraction of the cost.

Even fast ferries would be a better choice. Improving service on the island would be a better time saver for commuters on Staten Island

Agree with David Moog. This is an excellent history that delineates why a RR to Staten Island, or even the Cross-Harbor RR will likely never happen.

With regard to express bus, this is likely where the future can lie. But not just the existing express buses, rather a true bus network. I can imagine a busway, or HOV lanes along the Gowanus, that also provides for a few stops in Brooklyn along the way. For SI folks heading to Brooklyn, an actual transit option is now possible, because the express buses will make stops in places that are on the way to Manhattan that will also connect with key subway routes.

On the SI side, we are probably limited to bus lanes along key routes like Victory and Hylan. But if an actual busway can be created somewhere, or if a frequent service along an HOV lane can be created that connects to the Verrazanno, that can also be useful.

Could the costs of a Staten Island tunnel be justified if it was to carry an extension of the R Train from 95th Street-Bay Ridge to a new terminal near Fort Wadsworth, which could serve as a transit hub for other modes of transport on Staten Island, funnelling riders to it?

I will be looking at that very question in the second part, which I’m writing now.

How’s part 2 coming along?