On November 27th, 1967 there was chaos on the New York City subway. That Monday, as strap-hangers began their daily commute, many of them found that trains they had taken every day for years, decades even, were no longer running or were running to new places. Names like Sea Beach became the N, Jamaica became the RJ or QJ, Astoria became the RR, and terms like IND and BMT no longer meant the same thing. This was because one day earlier the NYC Transit Authority had quietly opened the most revolutionary new subway connection in a generation, the Chrystie St Connection. 50 years later we take this for grated but that day the way New Yorkers commuted on the subway changed forever.

The way New Yorkers thought about using the subway had been the same for over 60 years. From 1904 to 1940 there were three separate subway systems in the city run by the Interboro Rapid Transit Co. (IRT), Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Co. (BMT), and the Independent City-Owned Subway System (IND). Each ran their own service and there were no free transfers; at stations such as Times Sq or Union Sq riders would have to exit one system and pay a second fare to enter another (one major reason that fares had been kept at 5 cents for so long was due to this multi-fare system).

In 1940 the City finally succeeded in unifying the three systems into the NYC Transit Authority. The City had planned on connecting many existing lines into their IND system, but this hadn’t been legally possible until unification. After World War II the City was able to make small connections such as linking the IND South Brooklyn Line with the Culver Line (F train), linking the end of the IND Fulton St Subway with the BMT Fulton St Elevated (A train) in Ozone Park, and expanding IND Queens Blvd Subway service by connecting it with the BMT Broadway Line (R train).

These connections offered affordable ways to extend service along existing lines but didn’t create new services, save for the Queens Blvd connection which finally allowed for Queens local trains, formerly only run along the GG to Brooklyn, to enter Manhattan. Riders at the time still referred to their trains by name; take the Lexington Ave Express or the 4th Ave local and change to the West End line. Often times single lines had multiple services on them, some of which ran local or express. The naming convention made for long and confusing signage in stations.

Before World War II the core of the business areas in New York were cramped in Lower Manhattan. Wall St offered commercial space while the Lower East and Lower West Sides, which teamed with newly arrived immigrants, were the core of the garment making industry as well as other light industries. Dirty and dangerous, these areas were home to working class families looking for an escape which the subways provided. When the Williamsburg (1908) and Manhattan Bridges (1912) opened and extended subway service through Lower Manhattan it also opened up the far-flung districts of Brooklyn for new suburban growth and many families soon moved out to better quarters.

The BMT, which had been running elevated trains through Brooklyn for decades, began building their new subway lines into Manhattan. The majority of their system was downtown with only the Broadway Line heading uptown and into Queens, then mostly farm land. But as subways allowed cramped residents to flee to better locations so too did they allow businesses to move uptown where there was much more room to grow. By the end of World War II it was midtown Manhattan that was booming, but subway service was still focused downtown.

Subway planners saw this unbalance and devised an ingenious plan. The current subways had severe bottlenecks which held back service system-wide. 4 tracks would switch to 2, old junctions forced trains to pass in front of one another, and express tracks went unused. The solution was to, in one giant project, eliminate these bottlenecks and reconfigure the subway lines into Lower Manhattan to head uptown. First proposed in 1944 as part of the 2nd Ave Subway, the Chrystie St Connection would finally tie the two systems together in ways that unification hadn’t by adjusting the trunk lines, so the core of the system could handle more trains. (the IRT, built first with narrower tunnels, could not be connected to the BMT or IND). Planning began in 1954 and construction started in 1957.

While the project was named for the largest segment, a two mile tunnel below Chrystie St in the Lower East Side, it had a number of parts in order to fully take advantage of new connections:

- Rebuilding the DeKalb Interlocking south of the Manhattan Bridge so trains would no longer need to merge in front of one another.

- Building express tracks along the IND 6th Ave Subway from West 4th St to 34th St. These were left out of the original subway because of the exiting Hudson and Manhattan (PATH) tunnels in the way.

- A new tunnel and terminal station at 57th St and 6th Ave for additional 6th Ave local trains.

- Realigning the tunnels coming off the Manhattan Bridge. The south side tracks, formerly going to Chamber St, would now link up with the Broadway express tracks while the north side tracks, formerly connected to Broadway express, would head up Chrystie St.

- A new junction at Broadway-Lafayette Sts station with a tunnel turning south along Chrystie St.

- A tunnel under Chrystie St with a new station at Grand St. Supposedly this station was designed to allow for future expansion and connection to the 2nd Ave Subway.

- A new tunnel from Broadway-Lafayette Sts connecting to the BMT Centre St Line at Essex and Delancey Sts.

This complicated project was expected to take 3–4 years but ended up taking a decade to get everything in place. In 1965 the Transit Authority began looking at ways to help riders better navigate the soon-to-be connected system. Previous naming conventions would no longer apply since this new connection would allow for new routes and changes to existing ones. How would you describe a trip to someone if their journey began on the IND 6th Ave Line but ended on the BMT Brighton Beach Line? Subway maps had previously shown each system as different colors but with new lines intermingling how would this work?

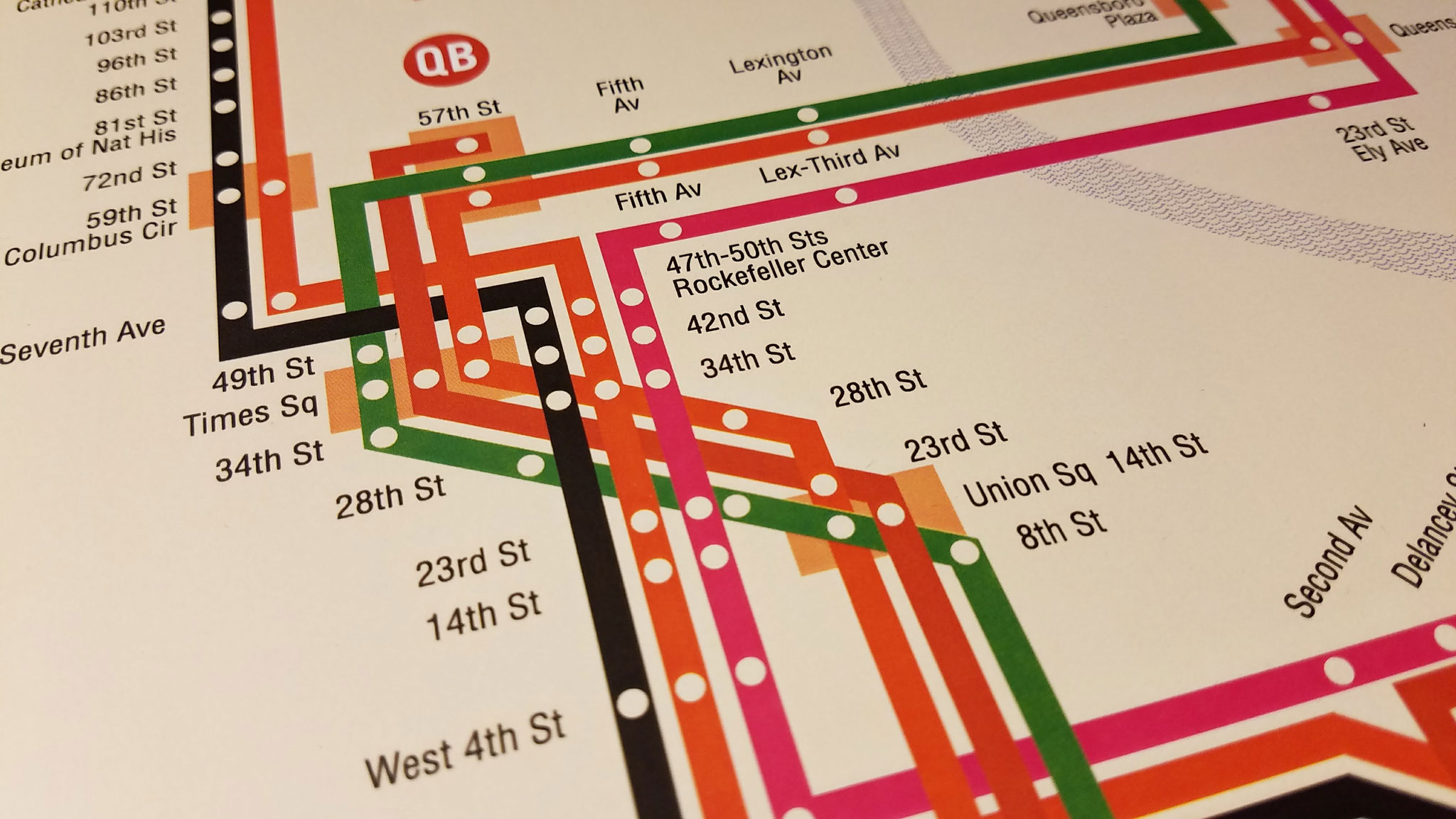

The TA hired Unimark, an industrial design firm headed by Bob Noorda and Massimo Vignelli, to help make sense of the changes. There is a rich and interesting history of how this happened so for brevity I will point you to Peter Lloyd’s Vignelli Transit Maps and Wired’s The Lost NYC Subway Map. The conventions that designers were settling on involved colorizing each subway line, showing the entire route rather than as branches, and changing line names to simple letters and number within bullets (lettered and numbered names had been used in the past but this codified the naming system and expanded it).

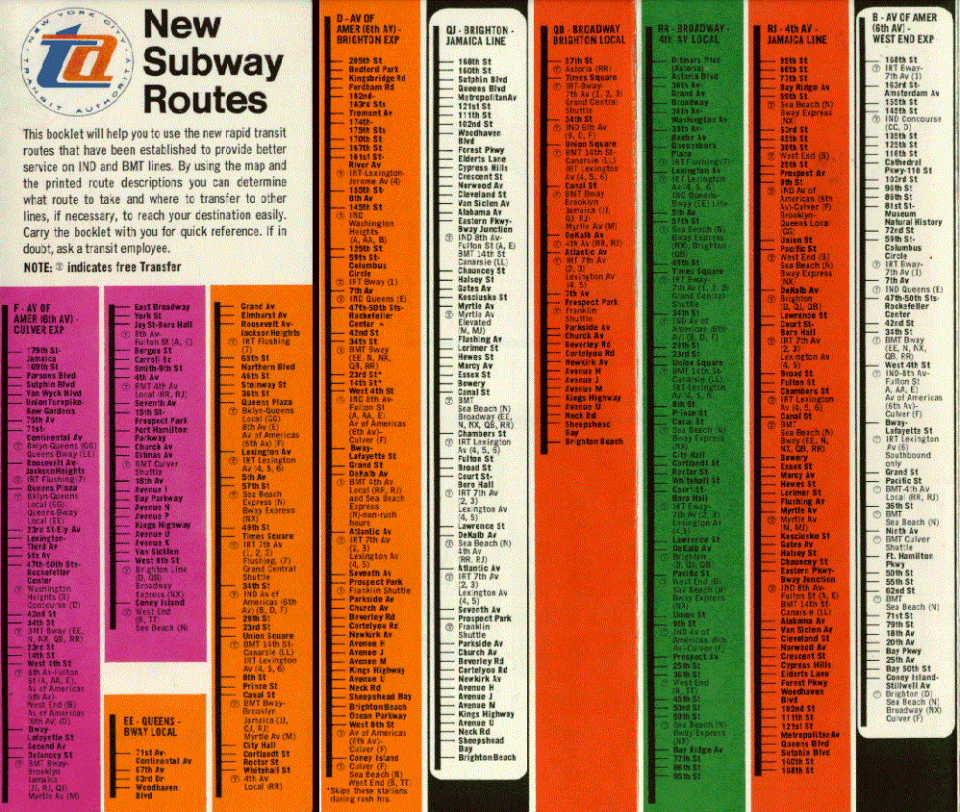

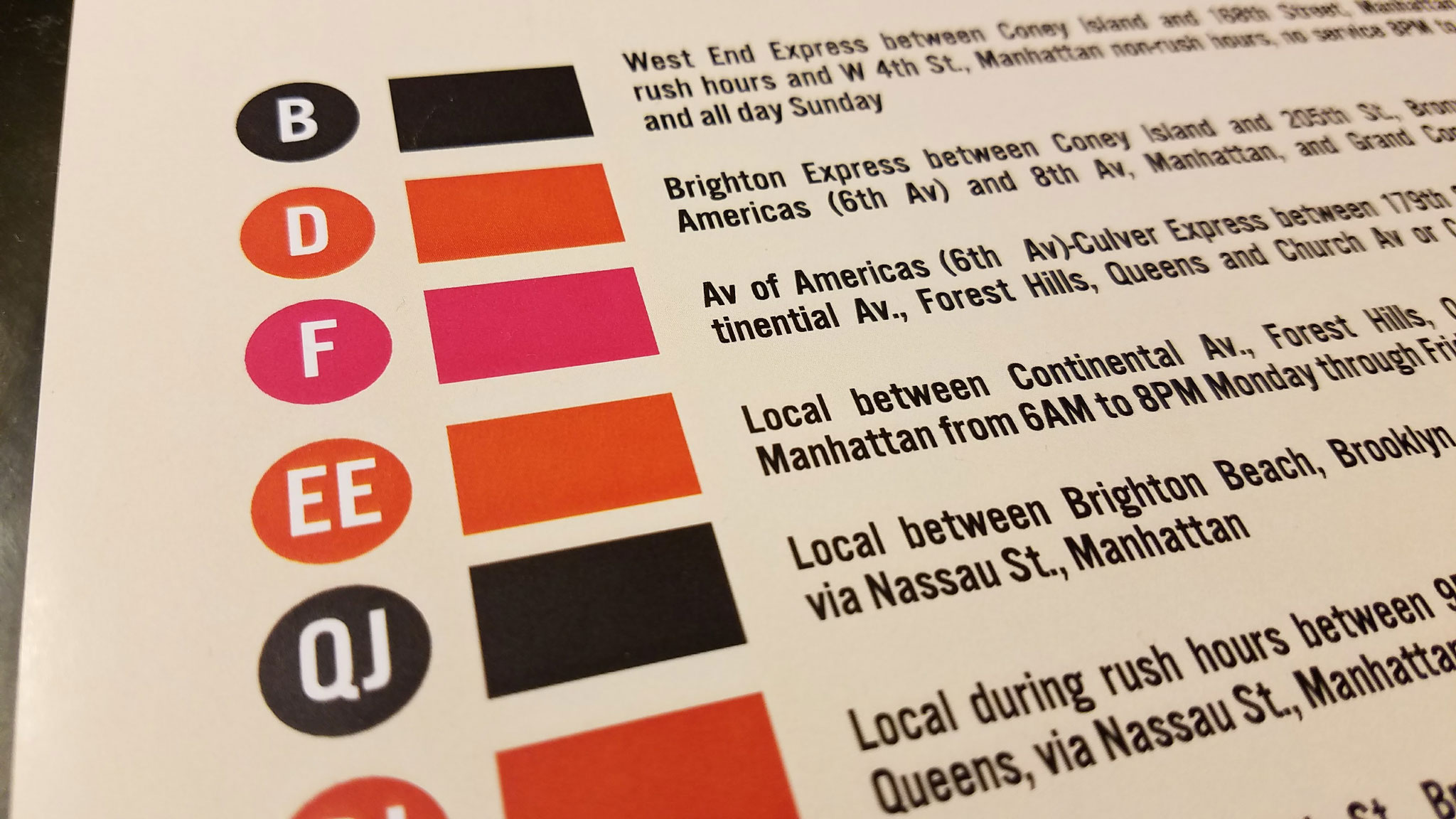

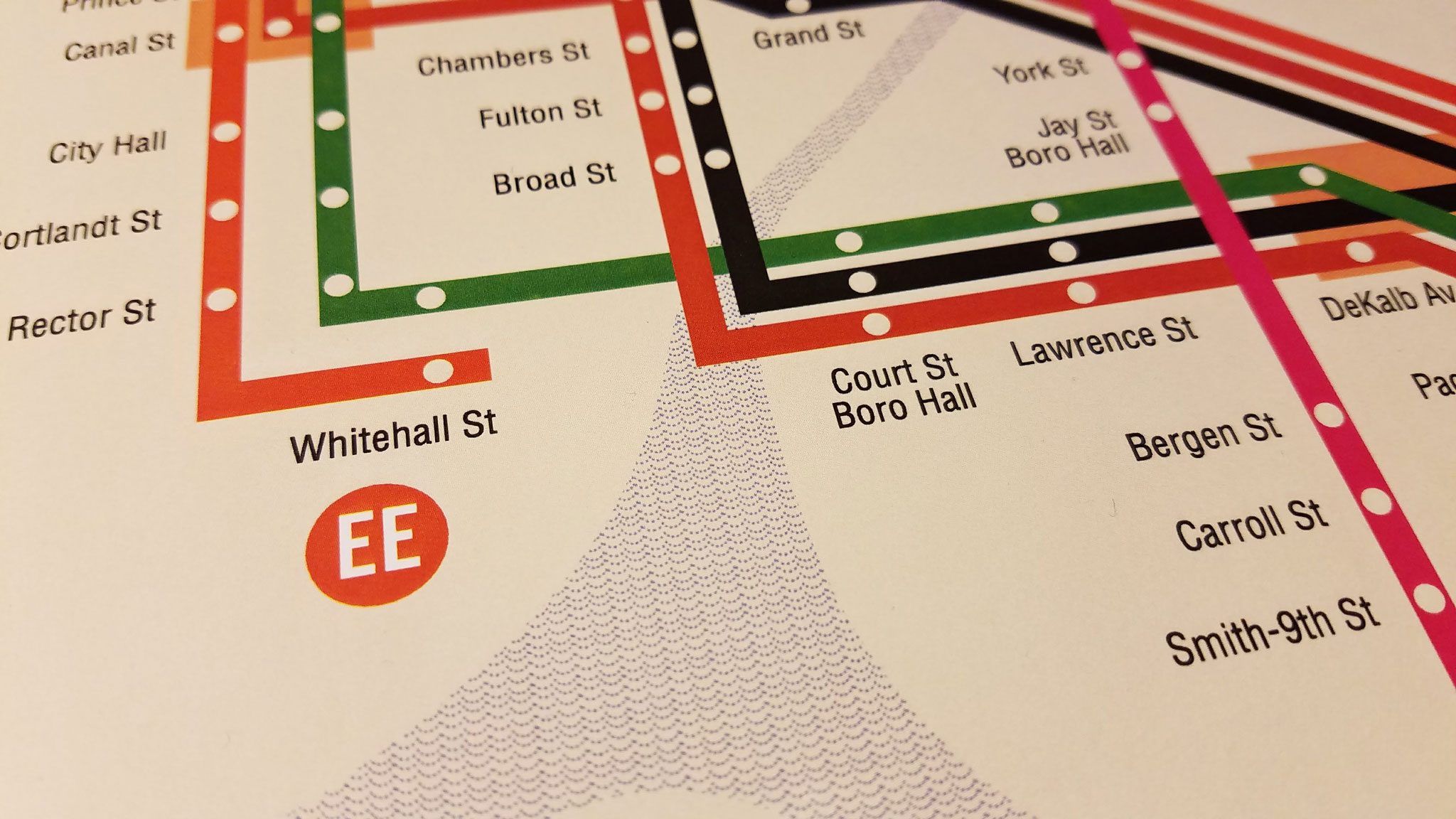

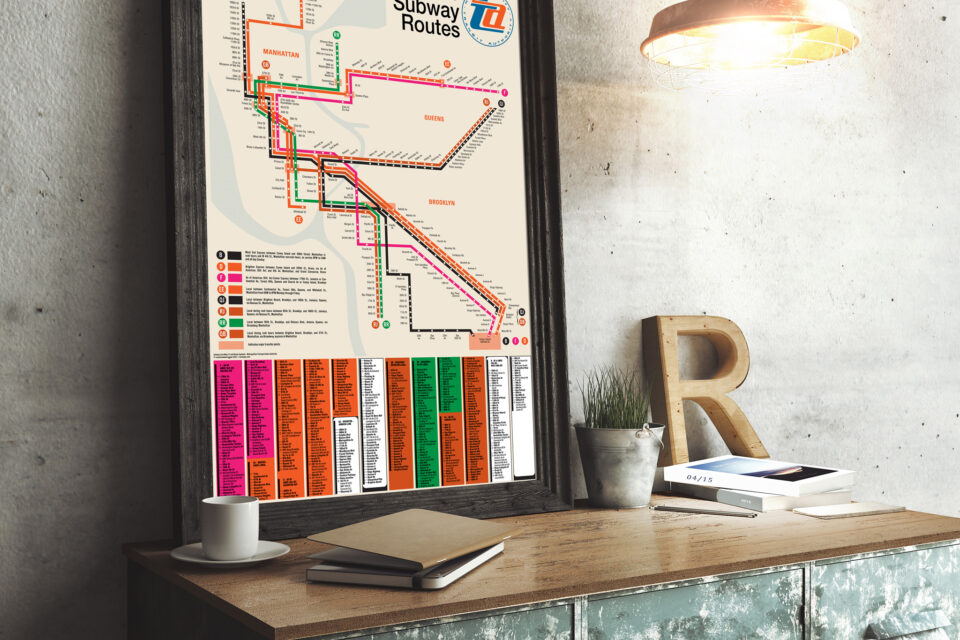

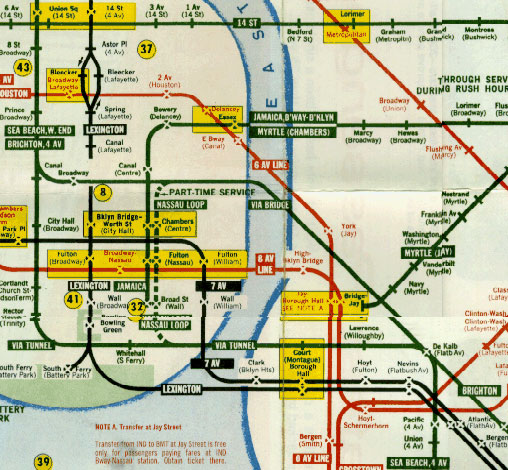

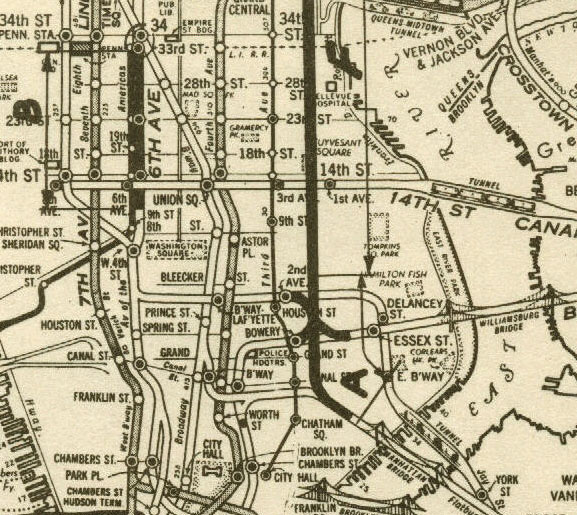

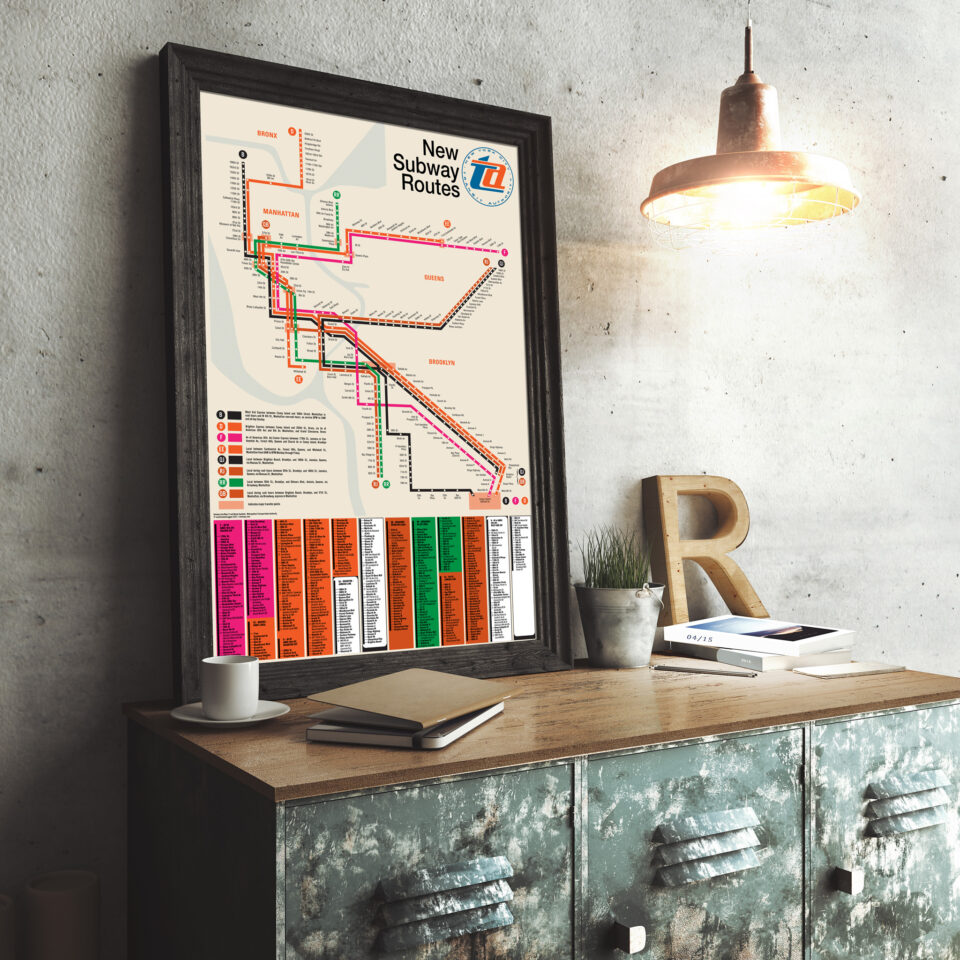

As Unimark continued on their wayfinding work the opening of the Chrystie St Connection loomed and the TA needed an interim map to educate the public on the changes. It’s unknown who was the designer of the New Subway Routes map, but it was using many of the design choices which would soon become prevalent throughout the system. The Unimark NYC Transit Authority Graphic Standards Manual was released in 1967 at the same time as Chrystie St but was so new that the signage in most stations had not yet been changed. Most trains didn’t have the new route names on them and the original roll signs still had their original names and destinations on them.

The famous Vignelli NYC Subway Map wasn’t to be released until 1972 so for riders entering stations on November 27th, 1967 they would have not been familiar with the new subway route name changes or the new subway maps with their colored lines. A brochure was printed with a prototype of the new system outlining the new routes, but it was not widely distributed. Chaos ensued. Riders got on the wrong trains and because train operators hadn’t been trained long enough on the new routes one Bronx bound conductor ended up running to Queens. State Senator Albert B. Lewis decried the changes stating

“I defy anyone to take this psychedelic creation and figure out how to get anywhere!”

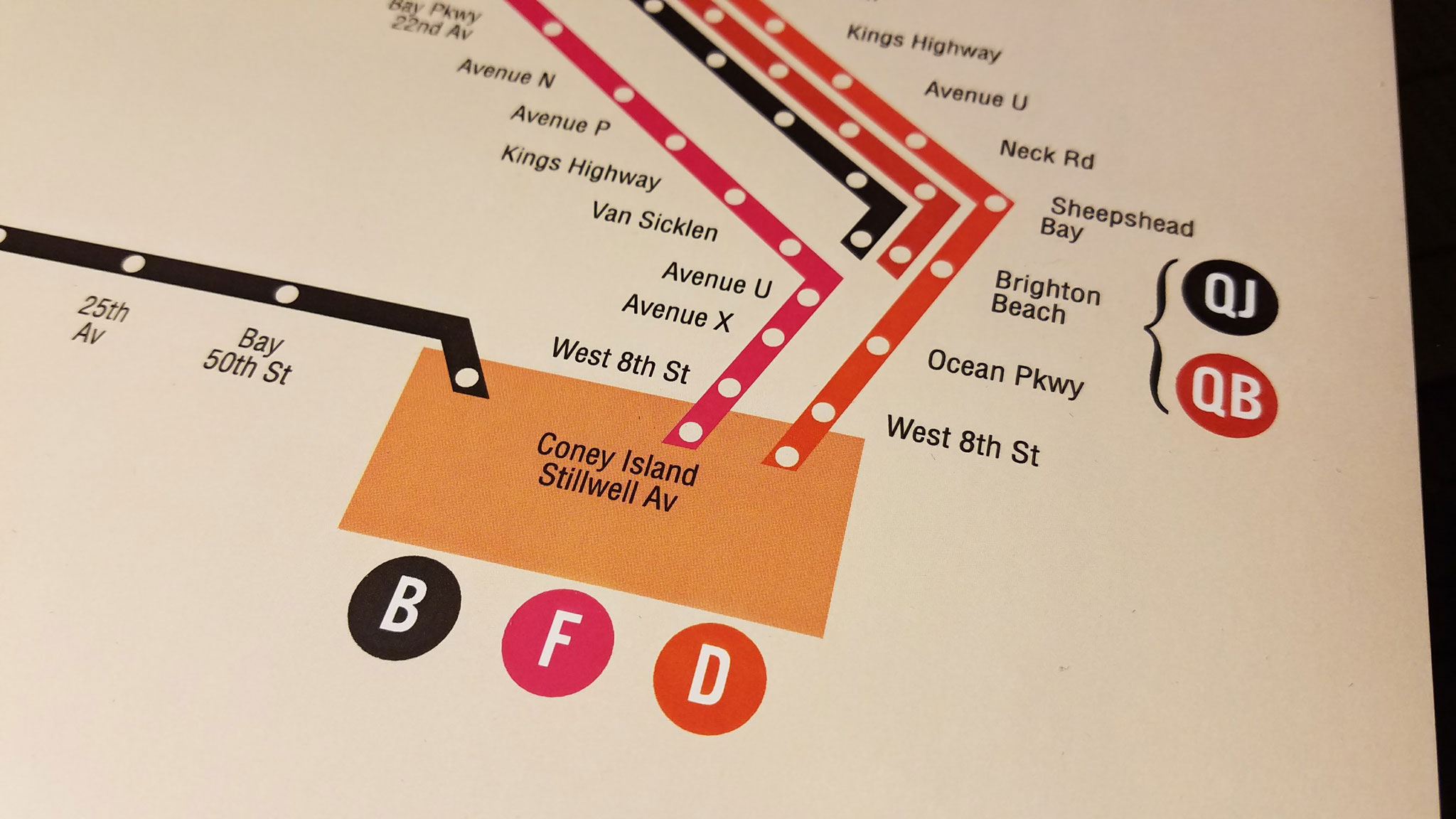

But soon New Yorkers began to adjust, as they quickly do, to the new routes. Once IND 6th Ave express trains terminated at 34th St, but now they continued south over the Manhattan Bridge to Coney Island, B trains replacing the T West End Line while D trains went to Brighton Beach. Trains from Coney Island which once had to turn back at Chambers St would now continue to midtown with more service along the RR (R train) and QB (Q train) lines.

A new super-express service was initiated, the NX, which ran from Brighton Beach through Coney Island-Stillwell Ave along the express tracks of the Sea Beach Line to 57th At-7th Ave. The new line was designed to give riders a faster ride to Coney Island, but ironically it was debuted in November, limiting it’s potential, and was ultimately axed in April due to low ridership. In June 1968 the Williamsburg Bridge connection was opened and a new service, the KK which replaced the still new RJ service, debuted from Jamaica to the new 57th St-6th Ave terminal. A new skip-stop service was also introduced to speed up service from Queens.

While Chrystie St increased capacity on existing lines, the new lines proved unpopular. Due to the overall decline in services citywide in the 1970s ridership dropped, and some lines were discontinued. The NX and RJ first and in 1976 the KK (now just K) was ended, removing direct midtown service from Jamaica. Service between southern Brooklyn and northern Brooklyn was cut back and lines like the QJ were simplified to the J.

The irony of Chrystie St is that it wasn’t fully appreciated in its time because of overall forces. But today we reap the benefits. In 2010 the M train, which until then had run to Chambers St and southern Brooklyn, was rerouted up 6th Ave, retracing the K train, as demand for midtown service grew in northern Brooklyn.

The B and D trains were swapped after the Manhattan Bridge overhaul and has proved a popular connection between the Manhattan Chinatown and Brooklyn Chinatown in Sunset Park. The skip-stop service first introduced on the KK and QJ is still in use with the J/Z trains. The changes to the subway would most likely have happened one way or another, but it was Chrystie St which ushered them in. Ask any millennial in Bushwick where to grab the Nassau St Line, and they will look at you puzzled (if they look up from their phone at all). Every time you use the subway map you are viewing the legacy of Chrystie St.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Chrystie St Connection I’m proud to introduce this limited edition recreated print of the famous “New Subway Routes” brochure. This map, while more familiar to modern eyes, was a shock to riders when it was released. The brochure was only for the new lines and didn’t include any unchanged routes. I’d like to thank Paul Shaw for his blog post on finding the typefaces used.

The IND was not around in 1904

I didn’t say it was. I said “From 1904 to 1940 there were three separate subway systems”, although I did not add start dates so this may have been confusing.

This is actually really cool. Never thought of the Chrystie Street connection like this, but if only SAS existed around this time

So basically the Chrystie St Connection basically shaped the majority of the present day 6th Av Line. Pretty cool though that Jay-Z got his stage name from the J/Z Line!

Are we going to have to wait a few months to see your next post? (p.s. I never knew how much the cry. st. connection affected the subway)

Probably. I need to get back to some big projects that are going to take up all my time.

The NX debuted in NOVEMBER….. genius job, MTA! Better than even Jimmy Neutron!

Right?! You’d think they might have even tried to bring it back in the summer just for shits but I guess not. It was a confusing route anyway and I feel like the decline of Coney Island might have had more to do with the loss of more express service.